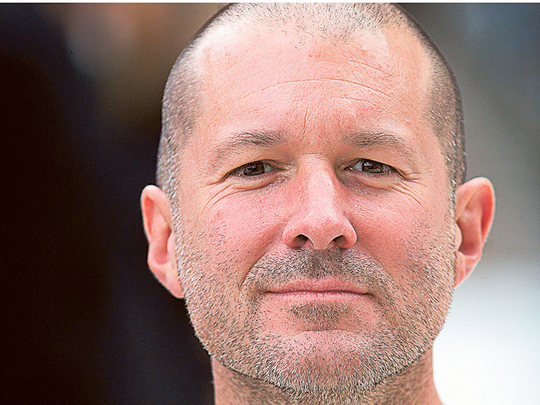

After two remarkably successful decades at Apple, Jony Ive is used to receiving honorary recognition. Sir Jonathan, who was born in Chingford in northeast London, was knighted for “services to design and enterprise” three years ago.

Last week, he gained the new title of chief design officer of what has become the world’s most valuable company, in large part due to his relentless efforts.

It hardly needed emphasising that Sir Jonathan is design supremo of Apple, and the decision to give him a grand title and promote two executives to run the industrial and software design divisions under him has divided Apple-watchers. Some regard it as a sign that Sir Jonathan is easing his way out, tired from producing a stream of innovative products such as the iPod and iPhone; others that he has accrued yet more authority.

Either way, he is at least the second most powerful executive at Apple after Tim Cook, its chief executive. Some regard him as the most powerful, thanks to his symbiotic relationship with the late Steve Jobs, Apple’s founder, who once described Sir Jonathan as his “spiritual partner”.

As Cook put it in the official announcement of his new role: “Our reputation for world-class design differentiates Apple from every other company in the world.”

Many other companies would like to match Apple by integrating design so deeply into the creation of new products and services that it outstrips functions such as sales and marketing. It has paid off for Apple to the tune of $760 billion — its current market capitalisation. Who would not want to mimic that?

The problem is that it is incredibly hard, even if a company has an equally talented team of designers. Not only is making things with more than a design flourish applied to the outside expensive, but the scope of design has expanded radically since 1925, when Philips, the Dutch company, hired Louis Kalff to polish its advertising and named him head of “propaganda”.

The cost of listening to what designers say is illustrated by one story in Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs. Sir Jonathan wanted to place a recessed carrying handle in the brightly coloured iMacs that he designed in 1998, less for practical reasons than to make the machine seem friendlier to older buyers. Apple’s engineers protested that the handle would be expensive and impractical; Jobs ignored them.

Good design runs deep. As James Dyson, the British inventor, argued in a recent interview in the Financial Times, “If something looks designed on the outside but doesn’t work well, you hate it. It gives design a bad name.” Thus, designers have to work from the earliest stages on what a product is, and how it will be built, rather than making it look good once it is close to completion.

One of Sir Jonathan’s heroes is Dieter Rams, the designer of Braun products such as shavers and radios. Among Braun’s design mottos is: “Good design is as little design as possible.” The tradition of being low-key and yet elegant, without any distracting details, is evident in the slim, almost austere, aluminium MacBook.

Apple does not solely follow the German functional style of industrial design. It also draws on a more exuberant US tradition, reaching back to mid-century designers such as Raymond Loewy and Harley Earl — the man who fitted fins to Cadillacs — in the colourful versions of iPods and other products. Sir Jonathan’s team somehow manages to blend the two approaches.

It is hard to remember now, but Jobs seemed to have set himself an almost impossible task on returning to Apple in the late 1990s — to resist the steady commoditisation of personal computers into a set of grey boxes containing software. By enlisting Ive, he both achieved this and altered where value lay — in the integration of hardware, software and services.

That makes the field of design more interesting, important, and difficult. Philips, for example, has 500 designers working in 18 global locations, whose work has shifted from making consumer devices to thinking about the way, for example, children in hospitals react to Philips-made body scanners. The more relaxed they feel, the less the need to sedate them.

Sir Jonathan was given oversight of software as well as industrial design at Apple in 2012. He now has a hand in everything from the layout of Apple stores to the design of its new headquarters in Cupertino, California, and the furniture inside. Apple is working on a car — maybe a self-driving car — and he is helping to steer this project too.

He has, in other words, made his job far bigger, extending his reach into aspects of production that an earlier generation of designers would not have dreamt of taking on.

This could account for his tone of profound weariness in a recent profile in ‘The New Yorker’. He described himself as “deeply, deeply tired” and only half deflected the suggestion that he would like to return with his family to live in the UK.

“Apple’s most remarkable quality is discipline,” says Jonas Damon, executive creative director of Frog Design, a design agency. “From the top down, they dictate what the company puts its effort behind.”

If being Apple’s great design dictator has become too much for Sir Jonathan, what chance do other companies have?

— Financial Times