Dubai: Islamic finance did not invent or innovate negative screening for publicly listed companies to arrive at a sub-universe of "ethical" companies.

In fact, Islamic equity investing is a subset of ethical investing, hence, there are shared values to do the "good by avoiding the bad."

The best way to explain these common values is to show how a typical conversation takes place between a financial consultant (FC) and a client.

After understanding the risk profile, investment objectives and time horizons of a client, what follows is a discussion on how the screening process works in layman's terms.

The first question to ask would be:

Are you interested in investing in companies whose primary business involves:

- Adult entertainment (pornography)

- Alcohol

- Gambling/hotels

- Tobacco

- Cinema and broadcasting

- Conventional insurance

- Conventional financial services

- Music

- Mortgage and lease

- Non-operating interest income

- Pork

Investors of conscious typically do not invest their hard-earned savings in the first four areas.

Obviously, they are interested in making money, but it's not a pure-play profits story for them.

Financial ratios

The FC then says there is another level of financial screening and it entails three ratios.

The first financial ratio entails how much debt or leverage a company has on its balance sheet. If it has more than 33 per cent debt-to-market capitalisation, then the company is removed from investment consideration.

The debt screen removes highly indebted companies, which many analysts, fund managers and stock pickers look at to assess the health pulse of the company.

Obviously, the debt-light companies are more in demand as they can better survive down markets, and many banks/bond buyers often impose debt covenants on the borrowing company. So, debt considerations are not a novel concept.

The next financial ratio is the accounts receivable of a company, it should not be more than 33 per cent of its market capitalisation. Thus, if the company is having difficulty translating sales into earnings, which can be used for internal funding, dividends for shareholders, acquisitions, then, obviously, its stock typically underperforms.

The final financial ratio is non-operating interest income, and it is expressed as a sum of cash, deposits and interest- bearing debt-to-market capitalisation of not more than 33 per cent.

It is basically flushing out the interest income analysis of the company. The company is relying too much on non-operating interest income, hence, these type of companies may actually under-perform its peers. Some may even be ripe for an acquisition.

Thus, a reasonable question would be: are shareholders investing in a company where the vision of its executives and board is focused on generating non-operating interest income rather than building growth plans that provide value to its customers?

After explaining the above screening process, the FC will then say they want to make sure the companies stay within the outlined parameters, so they will review the companies on a quarterly basis for continued compliance.

Obviously, the primary business of a company does not change often, except when acquired or merged with a non-industry player. It's the debt screen, debt-to-market capitalisation of not more than 33 per cent that results in companies being removed, but they are typically medium and small capitalised companies. However, to reduce the bandwidth of volatility associated with market capitalisation, as there may be sell-offs in the marketplace due to external events like the credit crisis, we would use a trailing 12-month average.

The FC then shows the top screened companies from the S&P Global "screened" Index.

As of March 28, 2011, the company names include ExxonMobil, Chevron, Nestle, IBM, Microsoft, P&G, J&J, BHP Billington, Coca Cola, and Novartis. One can see that these are global brands that are liquid and large capitalised organisations with a bias towards three sectors: technology, health care and energy. The client investor then says there is nothing Islamic about these sectors or companies, as these are headquartered and publicly listed in the western world and categorized as low-debt, non-financial ethical investing. Exactly!

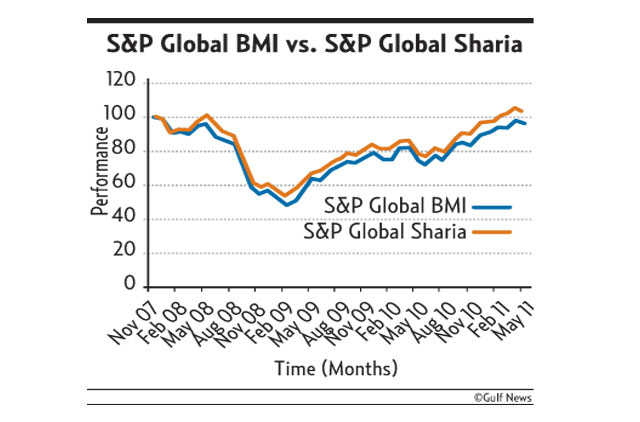

Finally, all the screening in the world is an academic exercise unless there is market performance and/or out-performance. Chart shows the S&P Global "screened" index (orange line) with not only a high correlation, but also outperforming the S&P Global BMI (black line) from Nov 2007 to May 2011, a period that included the credit crisis.

Thus, Islamic investing does not have a monopoly on doing good, by avoiding the bad, its common shared values with all investors of conscience.

The writer is Global Head of Islamic Finance at Thomson Reuters. Views expressed here are his own and do not reflect that of his organisation or of Gulf News.