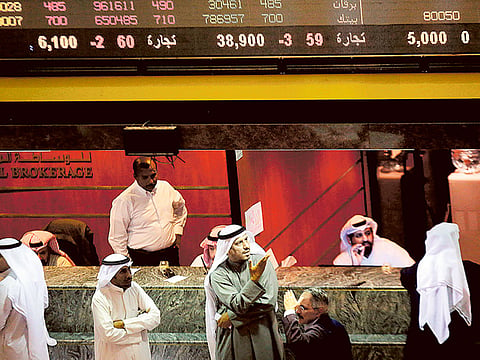

Concerns of Gulf investors could go well beyond oil

Rush for market exit looks like events catching up with expectations

Gulf stock markets are worried enough about plummeting oil prices and their drain on regional liquidity, let alone anything else. When you read reports, as in Barron’s this week, that commodity funds are positioned for $35 a barrel, that’s not particularly surprising.

While the US economy gives some countervailing hope of pickup, local investors might well worry too about downward trends in Asia, which was expected to be the next, thematic locomotive keeping business activity worldwide on track.

Moreover, there’s a parallel with this region in play, relating to the use of finance to leverage returns, inherently creating the scope for the current volatility. Debt has remained at the core, unfortunately, of both market and economic momentum since the global financial crisis.

Asia has borne witness to that phenomenon just as anywhere else, it seems.

Japan is soon to have another election, called to seek sanction for another phase of Abenomics, which so far has amounted to not much except yet further government-induced stimulus.

It has become apparent that China too is hooked on easy money, and, just as in the Gulf now, the rewinding of margin calls has prompted a sharp retreat, while the authorities try haltingly to wean the economy off its dependence.

And Asian emerging markets, so-called tigers in the world’s jungle, have been revealed as still much too reliant on China, on commodities, and on US-originated liquidity. Having borrowed largely in dollars, their corporates are encountering a triple-whammy of pressures from their main influences.

Common to all these concerns, in terms of economics, is an exaggerated focus on aggregate demand, whether motivated by the credit-driving banking systems or cash-generating printing presses of the state. Bluntly, some commentators just can’t get enough of it, ever.

It’s as if the cricket team that is the collective policymaking elite of the world’s leading authorities don’t want to look for the lost ball that was thumped into a deep and prickly hedge, so they insist on pacing frantically around the square on the infield, asserting that they’ll find it there sooner or later.

Demand is deficient, we hear, repeatedly. What we tend not to hear is that it’s not demand per se so much as demand relative to supply (prices and output) that’s really the issue in determining real growth.

For, when supply has been overinflated by excess amounts of demand, as is the case in previously prevailing boom conditions, it’s frankly puerile to imagine that bust can be avoided by carrying on in the same manner, or in fact intensifying the medicine.

That way, indeed, insanity beckons; there’s no getting away from it.

Perpetually negative real interest rates, and in some places negative nominal rates, only bring to mind to this commentator the feeling expressed in Gulf News over five years ago (when British prime minister Brown was ‘saving the world’) that key players don’t really know what they are doing.

Actually, that much has already been admitted, for instance by the US Federal Reserve, which keeps reinventing benchmarks that would prompt the eventual decision to opt for fractionally higher interest rates. The central bank has effectively said it can’t be sure what will happen at that point, and treats the pending moment with obvious dread.

Thus, the experiment more or less continues. We have a situation wherein US growth is quickening because of the natural resilience of its mostly free-market, deleveraging economy, but where equally Japan can hardly bring itself to address the multi-decade zombification of overdosing on state handouts, China too is intoxicated and fatigued by debt, and the Asian emerging markets are addicted to both Western and Eastern exhaust fumes.

Needless to say, a European economy hidebound by the self-contradictions of the Eurozone — and now shocked by the prospect of a premature Greek election that may cause further commotion — offers no help. Their eyes really are on a different ball: that of political ambition rather than economic sense.

So we’re all at sea in terms of understanding what to do and what may emerge, while the presence of so much indebtedness colours every aspect of the argument.

Rolling on stormy waters, and with an uncertain horizon until oil prices recover, it’s quite a gamble to suppose that global and Gulf stocks will close the credibility gap with underlying economies in a profitable way. We might instead be in for a series of false dawns.

Small investors should remind themselves that the best way to make money on stocks is to buy low, sell high and infrequently, limit your portfolio list, rotate it rarely, hold onto solidly good performers, reinvest dividends by the cheapest trading means … and turn to doing something else over time rather than obsessively following the stock market.

If not, they may worry themselves into an ulcer. Trouble is: prices aren’t really that low, yet. There’s no getting away from that either.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox