The smallest corn inventories in 37 years are a sign farmers around the globe are failing to produce enough grain to meet rising consumption, even as planting expands and food prices surge.

Growers from Canada to Russia boosted annual output of wheat, rice and feed grain by 16 per cent since 2000, not enough to keep up with the 20 per cent gain in demand, US Department of Agriculture data show. While a Bloomberg survey of 25 analysts shows the agency may forecast a 3.5 per cent increase in US corn planting, the government says world stockpiles will equal 15 per cent of use, the lowest since 1974.

Global inventories for all grain will drop 13 per cent before the next harvest, the USDA estimates. That's the first decline since 2007, when surging food prices sparked more than 60 riots from Haiti to Egypt. Increasing demand is causing isolated food shortages and accelerating inflation in developing countries even as it boosts farmers' incomes and shifts planting strategies.

"We need to grow a huge crop this year to meet global food needs," said Paul Jeschke, 58, who farms 3,600 acres [1,457 hectares] near Mazon, Illinois, and plans to boost corn planting by 50 per cent because the crop is as much as $200 (Dh734) an acre more profitable than soyabeans at current prices. "The increased demand for meat and dairy is driving demand for corn and soyabeans."

Rising incomes in developing countries are boosting food prices as people eat more meat and dairy products from crop-fed livestock. US subsidies are fuelling demand for ethanol made from grain, while droughts and floods in 2010 damaged global harvests.

Crop prices surge

Grain futures rallied this month to the highest since 2008 on the Chicago Board of Trade. Corn surged 95 per cent in the past year to $7.2025 a bushel as of February 18, wheat jumped 71 per cent to $8.5575 a bushel, and soyabeans advanced 44 per cent to $13.81 a bushel. Rice gained 11 per cent to $15.075 per 100 pounds.

Corn probably will reach a record $8 by 2012, and may touch $10 if the US crop is disrupted, said Peter Sorrentino, who helps manage $14.4 billion at Huntington Asset Advisors. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said on February 10 that soybeans will rise the most, forecasting a 16 per cent increase to $16 in the next three months. Wheat futures for delivery in December, after the US harvest, trade at a 72.5-cent premium to the May contract, the widest spread since 2009.

Multi-year trend

"People have to eat, and we have a backdrop of falling stockpiles," Sorrentino said by telephone from Cincinnati. "Even if we have a great harvest, we'll just be getting back to levels people can be comfortable with in terms of stockpiles. The trend is going to be for increasing prices for years to come."

The rally is encouraging farmers to plant more this year. The USDA, at its annual Agricultural Outlook Forum on Thursday in Arlington, Virginia, probably forecast an increase in US corn planting to 91.281 million acres from 88.192 million, according to the average estimate in the Bloomberg News survey. Soybean planting may be little changed at 77.274 million acres, the survey showed.

Including winter varieties already in the ground and spring crops that will be sown before June, US wheat farmers will plant a total of 57.206 million acres, up 8.8 per cent from a year earlier, according to the Bloomberg survey. Even with increased acres, output may drop because growers will abandon more of the crop this year after dry weather hurt yields, according to Lanworth Inc, a crop forecaster in Chicago.

The global grain harvest was 2.179 billion metric tons during the past season, dropping 2.4 per cent from 2010 and down for a second straight year, according to USDA data. While that's up from 1.874 billion in 2000, it's less than the department's 2.235 billion-ton estimate of world consumption for this year.

Inventories before the Northern Hemisphere harvests will fall to 425.72 million tons from 487.88 million a year earlier and 27 per cent less than what was on hand in 2000, the USDA said. Tighter supplies helped boost global food costs by 25 per cent last year, reaching the highest ever last month, according to the United Nations. The increase has pushed 44 million more people into extreme poverty since June, and the situation may worsen unless weather conditions improve and governments avoid trade restrictions, World Bank President Robert Zoellick said on February 15.

Commodity rally

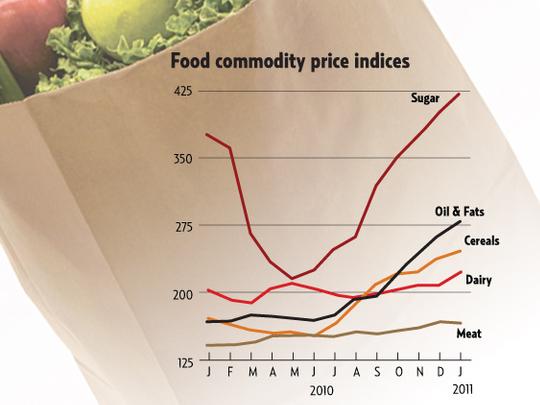

Grains weren't the only commodities to rally. Raw-sugar futures in New York rose to a 30-year high this month of 36.08 cents a pound, and cotton reached a record $2.0893 a pound on February 18 after doubling in the past year. Hog futures advanced this month to the highest since at least 1986 on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, cattle touched a record in January, and milk futures rose to a 31-month high last week.

Governments are planning investments to revive crop supplies. China will spend 12.9 billion yuan ($1.96 billion) to bolster grain production and fight drought, Premier Wen Jiabao told China Central Television on February 10. Bolivia may tap its record $10 billion central bank reserves to help boost agricultural output and stockpile food staples, Finance Minister Luis Arce said.

"Corn supplies are going to be extremely tight this year," said Loyd Brown, the president of Hertz Farm Management Inc. in Nevada, Iowa, who helps manage about 500,000 acres in nine Midwest states. "When you consider that US farmers harvested the third-largest crop last year, that means this is a demand market. You have to be bullish on agriculture. Global economic growth is driving demand for improved diets, and rising populations continue to boost exports."

Overseas purchases of agricultural products from the US, the largest exporter of corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton, probably jumped 18 per cent to a record $115.81 billion in 2010, the government said last week. China became the largest market for US farm goods for the first time, as shipments increased by 34 per cent to $17.5 billion, the data show.

China, the world's most populous nation, has been leading the demand. The number of people in the Asian country grew 5.3 per cent in the past decade, US Census Bureau data show. During that period, as the economy more than quadrupled, urban incomes tripled to 19,109 yuan in 2010 while rural incomes more than doubled to 5,919 yuan, according to the government.

"As developing economies expand and the middle class becomes larger, their logical step is to improve their diets," said Bill Lapp, a former chief economist at ConAgra Foods Inc. who is president of Advanced Economic Solutions in Omaha, Nebraska. "A significant share of that improvement is not simply more calories, but a better diet that comes from more protein and dairy consumption."

China, the world's largest pork consumer, boosted demand for the meat by 30 per cent since 2000 to an estimated 51.59 million tonnes this year, while beef consumption increased 6.7 per cent, according to data compiled by the US Meat Export Federation in Denver.

More grain is needed in China as livestock, dairy and poultry production shifts from small, family-owned farms with pastures to bigger, more-efficient industrial operations that feed animals mostly corn or soybean meal, according to Sterling Liddell, a vice president at Rabo Agrifinance, a US unit of Utrecht, Netherlands-based Rabobank Nederland NV, the world's largest farm lender.

About 7 pounds (3.2 kilograms) of corn is needed to produce 1 pound of beef, according to Perry Vieth, the president of Granger, Indiana-based Ceres Partners LLC, an investment fund that has bought and manages about 15,000 acres of farmland in four Midwest states.

US beef exports jumped to $4.08 billion in 2010, surpassing a record set in 2003 before an outbreak of mad cow disease led to import bans by countries including Japan and South Korea, according to the Cattlemen's Beef Promotion and Research Board in Centennial, Colorado.

Grain demand is rising worldwide. Saudi Arabia's cereal imports may reach a record this year, the UN said on February 3. Algeria, Morocco, Iraq, Bangladesh, Turkey and Lebanon issued tenders to buy wheat or rice this month, as food inflation stoked political unrest that toppled governments in Tunisia and Egypt. Wheat purchases by Algeria, North Africa's largest importer after Egypt, climbed to 1.75 million tons in January, according to Goldman Sachs. Rice prices have climbed to records in Indonesia, the world's fourth-most-populous country, and in Bangladesh, the biggest buyer in South Asia, the UN reported on February 3.

Bangladesh may double its rice-import target this year to cool domestic prices, as consumers and farmers hoard the grain, the nation's Directorate General of Food said. Indonesia is considering boosting stockpiles, and has removed import duties on wheat, wheat flour, soyabeans, rice and livestock feed. The European Union is suspending import duties on some cereals this week through June to ease pressure on prices.

The crop rally has been a boon to producers. On February 14, the USDA forecast net-farm income in the US will surge 20 per cent this year to a record $94.7 billion, allowing President Barack Obama to propose a 14 per cent reduction in agricultural subsidies in his 2012 budget proposal.

Farm-supply companies

More cash for growers means more spending on farm supplies and equipment. In the past month, Jeffrey J. Zekauskas, an analyst at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York, has raised his price targets for shares of Canadian fertilizer makers Agrium Inc, based in Calgary, and Potash Corp of Saskatchewan Inc, based in Saskatoon. Analysts at Jefferies & Co recommended this month that investors buy farm-equipment makers Deere & Co and Agco Corp, as well as crop-chemical and seed maker DuPont Co.

While US farmers want to plant more to take advantage of higher prices, many are already using the most-productive land, and the weather over the next eight months will remain a major influence on the size of any crop, said Dan Basse, the president of AgResource Co, a farm researcher in Chicago.

"We cannot rebuild the inventory cushion in one year," said Basse, who has been studying agricultural markets since 1979. "We have reached an acreage wall where the US can no longer be the world's pillar of exports for corn, soybeans and wheat."

Based on data available in November, the USDA estimated last week that US planting for eight major crops, including cotton, will rise 4.1 per cent to 255.3 million acres this year. The 10 million-acre increase would be the largest since 1996, when changes in farm legislation halted payments to farmers to idle land. The department will update that forecast this week.

Even a corn crop of 92 million acres "will not be enough to rebuild inventories because stocks are forecast to fall to 18 days of use," said Terry Jones, 49, who farms 7,000 acres of corn and soybeans with his brother near Williamsburg, Iowa, and 3,500 acres of corn, soybeans and wheat in eastern Oklahoma. He said he is looking to buy more cropland.

"We can plant more acres, but demand is not backing off yet," said Jones, who plans to sow corn on 67 per cent of his fields, up from 60 per cent last year. "Corn futures will likely rise to new highs, even if we have good weather this year."

In China, where a drought already is reducing yield prospects for wheat, unusually warm, dry weather may limit output of corn and soybeans that are planted before June and harvested by November, said Joel Widenor, the director of agricultural services at the Commodity Weather Group LLC in Bethesda, Maryland.

About 42 per cent of wheat fields in China's eight major growing provinces were hurt by a dry spell that may last into the spring, Minister of Agriculture Han Changfu said on February 9. The country consumes the biggest share of the world's wheat supply at 17 per cent, data from the London-based International Grains Council show.

Crops in North America face the biggest risk in the northern Great Plains and into the Canadian Prairies, where unusually cool and wet conditions will delay the snow melt and lead to late-season floods that push back some planting, Widenor said.

The main threat in the next three months will be for Plains winter wheat, where dryness will stress crops as they exit dormancy and begin to develop grain, Widenor said.

US corn and soybean crops may get warmer and drier weather than normal from South Dakota to Illinois to Texas, he said.

"This has been a demand-driven bull market," said Jim Farrell, 56, the chief executive officer of Omaha-based Farmers National Co., which manages more than 2.4 million acres on 5,000 farms in 24 states.

"I do not think we can see a big enough increase in US acreage to rebuild inventories back to a comfortable cushion in one year," he said.

"It is going to take two years of good weather and good yields. There is absolutely no room for any weather problems anywhere in the world this year."

Have Your Say

Do you believe this is true? What is the solution to combat this problem? Let us know what you think