Dubai: There is no let-up in the Gulf states' fascination with aluminum. For Dubai and Bahrain, the respective smelters — Dubal and Alba — have long been exemplars of their assured progress in the non-oil manufacturing space.

More recently, Abu Dhabi joined Emirates Aluminum (emal), Oman has had success through a smelter in Sohar, while Qatar came through with Qatalum last year.

Saudi Arabia is preparing a mega smelter for commissioning in 2013. Total investments in these smelters have crossed more than $35 billion (Dh128.53 billion).

This is why the coming together of these smelters under the umbrella of the Gulf Aluminium Council (GAC) represents a pivotal moment for the metal in the region. The GAC has just been set up, but it intends to be a determining factor in the ebb and flow of a highly cyclical industry.

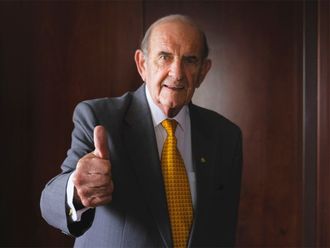

Formerly a deputy chief executive at Alba, Mahmoud Daylami has been named the GAC's first general secretary. He talks to Gulf News about the many opportunities — and quite a few challenges — the entity will look to take up in the coming months.

Gulf News: The moment one hears of heavyweights in a particular industry joining hands, red flags are raised over the possible creation of a cartel. How would you counter that?

Mahmoud Daylami: Aluminium is a different business compared with many others, including oil. Our industry is governed by anti-trust laws in all of the major markets and that makes creating anything resembling a cartel illegal.

Whatever else GAC might do, one thing we won't is try to set prices for the commodity. After all, the pricing is decided by global market fundamentals and at the London Metal Exchange on a weekly basis.

We are different from other industry groupings in that we are more of a business-orientated body. We don't stand for lobbying.

Eventually we will have to. We try to see what the common needs are and how we can address them optimally. It could be related to technology, could be logistics, or do with purchasing or common contractual agreements. It would even relate to environment or human resources.

Even now fresh smelter capacity is being raised in the Gulf, which is arguably excessive. What is GAC's response to that?

There's this constant misunderstanding about cap-acity and the need to add more smelters. In fact, one smelter is one too many for the real consumption in the Gulf.

But the smelters in the Gulf are not just to satisfy demand in the area and the markets around it. It's value-added and export-oriented for the international markets, and that means 80 per cent of the output is headed out.

We are now producing aluminium as a primary product, but there are a lot of downstream industries in the Gulf which can take primary aluminium and convert to different products. For instance, Dubal and Emal do not produce windows, but others buy the output and convert it to profiles.

Other buyers come in for the profiles which are converted to windows and doors. There are so many secondary and tertiary end-users in the Gulf, and that's how new value is being created constantly.

There's room for investments on the downstream side on much higher value-added industries. Not just doors and windows, but engines, in areas related to casting, etc. That should be the focus in future.

What about new smelters?

Apart from those projects that are nearing completion, I don't think there will be new smelters coming up in the area. But there's a good chance of expanding existing ones.

Alba could go for one more potline expansion. They are studying it, they have five now, and could go for the sixth. Dubal could expand, emal certainly would. Saudi Arabia will have new capacities in the future; Sohar in Oman has room for it.

Saudi Arabia is building one now and it's a massive investment of $10.5 billion in a joint venture with Alcoa (which holds 25 per cent). It will have a process that goes from refining the bauxite to smelting to the finished product. The commissioning is set for 2013.

Aluminum production in the Gulf will reach four million tonnes by 2014.

But there's talk of some imports being cheaper than even locally manufactured aluminum. How can Gulf smelters counter that?

The price of aluminum is set internationally, and it doesn't matter whether end users buy it from the Gulf or outside. Of course, there are the transportation and other logistical costs.

It will not be cheaper to import unless Chinese manufacturers sell it below the market price, and they have been known to do that.

There's a lot of legal action against that taking place in different countries. And it's an issue we are keeping a close watch on before taking any action. When you source from within this area, prices tend to be cheaper and labour costs lower.

What will be the GAC's priorities?

Our power does not lie in changing legislation; it lies in the providing of factual advice and information. We know the product and the industry more than the people in the ministries concerned. For instance, we will not claim someone dumping unless we have the facts. That we can provide.

Aluminum prices have recovered a lot. Do you expect more?

It's $2,400 plus. It's a good price, and way above the cost of production of smelters in the region. It's a healthy business at the moment. The prediction is for a further hike, but how high I don't know.

Obviously, there's a lot of inherent demand that's coming to the surface, isn't there?

It, of course, has to do with the global economy, the cost of energy and other fundamentals.

Fifty per cent of the aluminum produced around the world is used in transportation and construction. Both sectors are highly linked to global economic health. During the crisis, automobile production went down and everything else came down with it, including aluminum prices. Now it's getting healthier, which has different reasons going for it. One is that the energy prices are high and the dollar is low.

The current world demand is around 40 million tonnes and the projection is for at least a five per cent increase in demand annually. By 2020, demand is expected to be 74 million tonnes, which means we need new production facilities of more than 30 million tonnes within the next 10 years.

What about competition from smelters elsewhere?

In recent days, there have been reports that a few smelters in the US are going to restart. It's a big signal that the turnaround is happening for the metal.

But in Europe, because of the cost of energy, many smelters had either downsized or closed down.

If this continues, the Gulf is well-positioned to be a global centre for aluminum production. Currently we produce seven per cent of the world's output and I see the share going up to ten per cent. The Gulf countries, China and India will be the main producers as well as Canada, Brazil and Russia. The West will gradually reduce output due to ageing plants and high energy costs.

The majority of new demand will be from China which is estimated to be around 40 million tonnes by 2020. Currently it is 16 million tonnes.

Gulf-based smelters have historically relied on gas as feedstock. Do you think there's a chance it could shift to processes that are more environmentally conducive?

Right now there's no alternative to gas. Moreover, the more the operational efficiency of the smelter, the better the use of the energy produced by the power station.

Gulf smelters, because they are new and have been modernised extensively, have high efficiencies.

Worldwide, you need 15.4 kilowatts (Kw) to produce one tonne of aluminum while in the Gulf it's 14 Kw. That's one way of looking at reducing the environmental impact. Also, local smelters have investments of $500-$700 million on environmental equipment alone. These are significant commitments.

By-product treatment

Under the umbrella of the Gulf Aluminum Council, the region's leading smelters are doing a feasibility study on a dedicated plant for treating by-products.

Once treated, these would have commercial application in industries such as cement production.

"Because smelter capacities were smaller in the past, it was hard to justify an investment in such a plant," said Mahmoud Daylami of GAC. "Now we have five smelters in the Gulf and a sixth is on the way.

"The quantity of by-products that will be generated is enough to justify a recycling plant now."

There's a relining material in smelter pots that should be changed after every five or six years. The material would be reprocessed if the proposed treatment plant comes into being.

"A new plant can take care of this in an environmentally-friendly way," said Daylami. "The technology was not there before. It's there now.

"This is available in Europe, and we have now assigned a technology provider to carry out the feasibility study. The location of the plant and the investments would be decided later."

GCC aluminium import duty

The stalled negotiations with the EU over the longstanding and vexed issue of the six per cent duty on GCC aluminum imports could be revived.

"Negotiation stopped last year. Now there's talk about restarting them soon," Daylami said. "The six per cent is hurting both the Gulf as well as consumers within Europe because they have to pay more.

"All because there are some people benefiting from it in between."

The six per cent duty on GCC aluminum has been in effect for 20 years. "The players keep changing and so do the arguments," Daylami added.

The stalled negotiations with the EU over the longstanding - and vexed - issue of the 6 per cent duty on GCC aluminum imports could be revived.

"Negotiation stopped last year, now there's talk about restarting them soon," said Mahmood Daylami of GAC. "The 6 per cent is hurting both the Gulf as well as consumers within Europe because they have to pay more. All because there are some people benefiting from it in between."

The 6 per cent duty on GCC aluminum has been in effect for 20 years now. "The players keep changing and so do the arguments," Daylami added.

"It was started as a protection measure by aluminum producers in Europe and then became part of the free trade negotiations between the Gulf states and EU. The other side is using aluminum tariff as a bargaining chip to try and receive concessions in other areas.

"All of us are hoping that a breakthrough will happen at some point."