Just when Formula One (F1) thought that world champion Nico Rosberg’s shock departure last month was as seismic as it could get, it has been proven wrong. Bernie Ecclestone, F1’s supremo for the past 40 years, was dismissed by the new owners, Liberty Media (now renamed as the Formula One Group) last Monday.

It is the end of an era as Ecclestone has been a constant presence in the undulating path of F1 history.

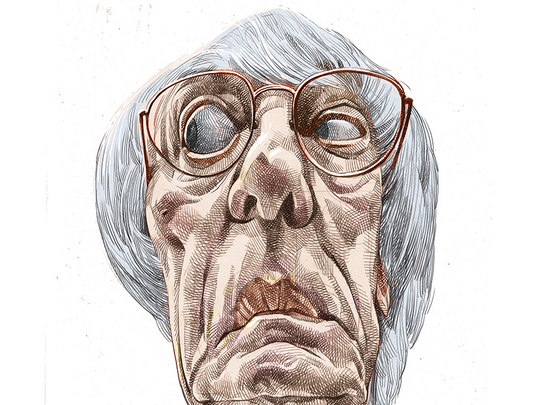

Ecclestone makes for an unlikely figure — only 5 feet 3 inches tall, bespectacled and forever wearing a white shirt and black trousers.

Bernie — or “Mr E”, as the paddock called him — has been the single-most important person in F1, running the sport as his own fiefdom. No wonder, then, that Chase Carey, Ecclestone’s replacement, has labelled him a “dictator”.

Despite being worth an estimated $3.1 billion (Dh11.40 billion), Ecclestone was notorious for the cheapness he displayed in his personal life. He had once famously said that he did not know the price of drinks at hotels, because he refused to buy them. His controversial reputation followed him throughout, including his admiration for the leadership styles of Adolf Hitler and former Iraq president Saddam Hussain and his remark that women were akin to domestic appliances.

When Ecclestone’s association with motorsport began, selling motorcycles and second-hand cars in Bexleyheath, London, in the 1950s, his name was not even first on the side of the company van.

But Ecclestone did not take second billing for long.

Through a mixture of vision, cunning, business acumen and an insatiable appetite for profit, he transformed Formula One into a global entertainment property, and himself into its emperor.

Now, aged 86 and against his volition, he has been deposed.

Growing influence

When he first entered motorsport, it was a cottage industry. The cars were largely built by privateer teams run by enthusiasts. The drivers were heirs to a post-war generation, whose notions of risk were forged flying Lancaster bombing raids. This was a sport where some opted not to wear a seat belt, believing it was better to take their chances being thrown clear of a wreck than be strapped to a burning fuel tank.

He started as a driver representative, but his influence grew as owner of the Brabham team. Persuasive and charming, he became the team’s spokesman in negotiations with circuits, broadcasters and the governing body, the FIA. He was a natural and F1’s income swelled, although he was reticent to share any of it. He made deals and negotiated without notes, records or much investigation from his peers. As long as the money poured in, they were happy to let Ecclestone do business.

By the early 1980s, F1 was on the crest of a wave as esteemed drivers such as Alain Prost, Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell and the great Ayrton Senna battled against each other in formidably engineered machines. That golden era ended in tragedy in April 1994, when Senna and the Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger were killed on the same weekend at Imola.

Safety, therefore, became Ecclestone’s focus and he was also blessed with a new star in Michael Schumacher, who went on to become a seven-time world champion.

It was not as competitive or quite so compelling, but F1 continued to blossom and Ecclestone consolidated his power.

The lengths he would go to protect his empire became apparent in 1997, when the revelation that Ecclestone had made a £1 million (Dh4.61 million) donation to Britain’s Labour Party shortly before F1 was granted an exemption from a tobacco advertising ban plunged the then British prime minister Tony Blair into his first crisis. By then, Ecclestone had already struck a deal with then FIA president, Max Mosley, that gave his company, rather than the teams, control of the F1’s commercial rights.

Astounding deal

When the teams protested, he bought them off, and in 2000 he paid Mosley’s FIA $360 million for a 110-year lease on the rights. It was an astounding deal, from which Ecclestone and his family trusts were to make billions. The rights were sold and re-sold several times, with Ecclestone retaining control each time, but his last but one deal was almost to cost him his liberty.

By 2006, more than 40 per cent of the business was owned by a Bavarian bank, creditor of the previous owner, German TV company Kirch, that had gone bust. On trial in Munich in 2013, Ecclestone claimed he made the payment after being blackmailed by the banker, who was threatening to go to the Inland Revenue. The last thing he wanted, he said, was a huge tax bill.

Once again, Ecclestone cut a deal to stay afloat, paying €100 million (Dh392 million) to settle the case “without guilt or innocence being established”. It ensured he lasted three more years in the circuit, but it was the beginning of the end as F1’s development began to stall.

He failed to embrace the potential of social media and he abandoned the sport’s traditional European base in pursuit of the filthy lucre.

Ecclestone transformed the sport and made many people very rich, none more so than himself and his family.

But at 86, even he has run out of road, with new owners Liberty Media eager to eye new ideas and younger markets.