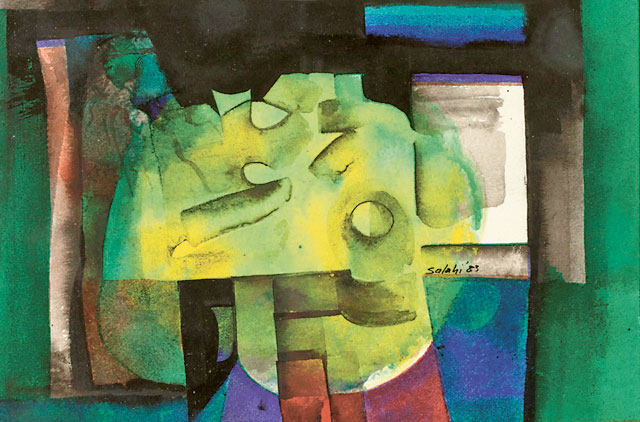

Well-known Sudanese artists Ebrahim Salahi and Mohammad Omar Khalil have been living abroad for many decades. Their subjects, inspirations and styles are eclectic, but their work continues to be influenced by their Sudanese heritage and still has an influence on contemporary art practices in their country. Art Sudan, their first joint show together, offers a retrospective of the work of the two artists, giving art lovers in Dubai a rare look at contemporary Sudanese art.

Salahi, who is in his eighties, was the first Sudanese artist to study abroad. After getting a diploma in painting and calligraphy from The Slade School, London, he returned to play a pivotal role in changing the British influence on art education in his country and encouraging young artists to reconnect with their north African and Islamic artistic heritage. Besides working as an adviser to the culture and information ministry in Sudan, Salahi has held similar posts in Qatar and Somalia, making significant contributions to the development of art in the region.

Khalil, who is based in New York, graduated from the School of Fine and Applied Art in Khartoum and studied fresco painting and mosaics in Italy. The 75-year-old artist is a painter and engraver, and has taught at prestigious universities in the United States. He also regularly travels to Morocco to conduct workshops in engraving. He is showcasing two series of engravings, created between 1986 and 1997, and a recent set of collages.

One set of engravings is inspired by the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. Here, the sharp silhouettes of the city, carved out from rocky cliffs, are combined with materials such as lace and wire mesh to convey not just the look of the place but also its history. "I wanted to create a panoramic view of this stunning, hidden city. But I also wanted to connect with its past. Petra was an important trading centre before it was taken over by the Romans.

The delicate lace and the curtain-like mesh pressed on top of my engravings represent the people who once inhabited what is now a deserted city of empty buildings and dark, windowless rooms," Khalil says.

Titles such as Idiot Wind and Tombstone Blues suggest that the other series of etchings is inspired by the music of Bob Dylan. "I love Dylan's music and listen to his songs while working. This series was created just after my wife and I separated. During this emotional time, I poured all my feelings into interpreting Dylan's songs through etchings. The piece titled Idiot Wind is divided into two halves depicting a calm and a stormy atmosphere. I deliberately did this work in two pieces to represent our split, and since then every engraving I do is similarly split," he says.

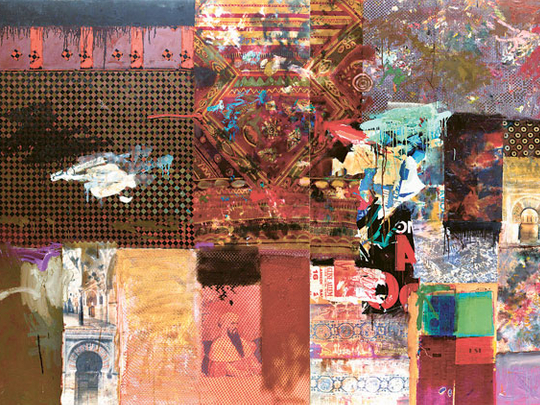

Khalil's latest work is a set of striking collages reminiscing on his memories and impressions of a recent trip to Andalusia. The artist has used oil paints, fabrics, wire mesh, digital images, newspaper, posters and even his neck ties to bring alive the rich Moorish heritage of the area. Once again, he conveys not only the beauty of the place but its history as well. He also subtly links the past with the present to give his work contemporary relevance.

In Cordoba, he has recreated the opulence and beauty of a city that was once one of the richest and most cultured places in Europe. The collage features aged images of the impressive mosque, the Moorish ruler who built it and the church that was later built inside the mosque. The composition also includes copies of gold coins from the period, fabrics painted with patterns from those times, textures created with wire mesh, painted neck ties and splashes of colour that express myriad emotions. Cuttings from current newspapers, often from sheets used by the artist to clean his printing rollers, provide a connection with present times.

"This work represents the sum of all my feelings regarding the chaos happening then and now in the world. Nothing has changed. Society is still plagued by religious strife, cultural conflict and economic crises," Khalil says.

The grandeur of the Alhambra palace in Granada is similarly depicted in another collage. While textiles painted with flowers commemorate the beautiful garden in the women's quarter, dark patches recount the years of neglect after the Moors were defeated. Images of a sundial and the famous Fountain of the Lions, whose intricate mechanism baffled the Spaniards, comment on the inventions brought to Europe by the Arabs. "The advances in medicine, navigation, mathematics, astronomy and other fields brought by the Arabs changed the whole of Europe. But, sadly, the Western world prefers not to acknowledge this contribution and depict them as uncivilised barbarians," the artist says.

The final canvas in this series is titled The Moor's Last Sigh. It depicts the exodus of people from Granada with a quilt of various fabrics representing the mix of ethnicities. The last Moorish ruler, Abu Abdullah, is represented by images of a retreating horse and of his grave in Morocco, where he died fighting the Spaniards. And a sign saying "NO PARKING — By Order of New Management" adds a witty, contemporary twist to the tragic tale.

Khalil has been living in New York for more than 25 years and two decades went by when he did not visit Sudan at all. Yet he believes that all his work is influenced by his country.

"You can never be separated from your roots. Wherever I am, I carry Sudan inside me. I feel choked with emotion whenever I am told that my work has a Sudanese ethos. I was not able to go and see my father before he passed away, and everything I do reminds me of him and of my country," he says emotionally.

"I have been travelling to Sudan regularly for the past seven years now and it is my dream to set up a studio for print making there, which will help me share my skills and experience with young Sudanese artists," he adds.

Jyoti Kalsi is an art enthusiast based in Dubai.

Art Sudan will run at Meem Gallery, Dubai, until February 5.

The six stages of Ebrahim Salahi's career

Ebrahim Salahi, who lives in England at present, has seen many twists and turns in life, ranging from being a respected national figure to a political prisoner in his country. And these are reflected in the changes in his work during different periods of his career. After returning from England in 1957, Salahi tried to unshackle Sudanese art from British influence by exposing students to traditional crafts. He even brought craftsmen from villages to teach in schools and used calligraphy to connect youngsters with Islamic artistic traditions.

In his ball-point pen and Indian ink drawings from the 1980s, human figures and arabesque patterns combine to create a unique vocabulary. The artist does not use sketches to create these layered, multipanel artworks, but allows them to grow organically from a central idea. In later works, he has used coloured inks to present his contemporary version of familiar sights, such as a bridegroom on a horse, a person seated on a ‘bambar' and the ‘jubba' worn by men from the Mahdi clan. In the past decade, his work has become increasingly minimalistic and abstract. A recurring motif has been the tree. In his recent work, this is represented by a series of straight and curved lines, which make his compositions beautiful in their simplicity and sophistication.

"I have been a picture maker since the 1930s, when as a child I began to decorate my slate with ‘sharafah' motifs, a combination of Arabic calligraphy and geometric designs. My work has kept changing and it has gone through six main stages. During the 1940s and 1950s, when I was training in art at high school and art college in Sudan, I was interested in the visual representation of nature, man-made objects and calligraphic symbols. From 1954 to the early 1960s, during my stint at the Slade School, London, I was fascinated with the study of perspective and all aspects of the law of vision.

"During the 1960s and 1970s, after I returned to Sudan, I was shocked by the lack of interest among the people there. This made me think deeply about the artist's role in society. I became aware of a missing link and the need to establish a common ground with the public. I found the answer in Arabic calligraphy and African motifs and a sense of design as a comprehensible pictorial idiom. I then understood the significance of what I had learnt in childhood, and the importance of cultural heritage as a vital element in our sense of aesthetics and art. This became the basis of what became known as ‘the school of Khartoum'. The fourth period, in the 1970s was a period of stagnation caused by unfavourable conditions. While in jail, I conceived the idea of the organic growth of a picture. Later, when I was out but still under surveillance, I turned to bright colours and abstraction to get rid of the bitterness and agony.

"Then till the mid-1990s I worked only with black and white, in search of a balanced grey tone. During this period, which marked the beginning of my voluntary exile from my homeland, I developed the idea of organic growth of a picture around a nucleus, reflecting the relationship between part and whole that exists between the individual and society. I began to group together separately framed panels to build up a picture.

Since the 1990s to the present, my aim has been to create artworks that are an invitation to meditation. I am aware that art should be addressed to three entities — self, others and all. Hence, in much of my recent work, I have chosen the Harazah tree as a symbol of the individual in society. The tree has the unique characteristic of being green when everything around it is dry, which to me represents being alone and together at the same time. "I believe art is an organic process and should evolve spontaneously from the nucleus of an unknown idea. And rather than using colours, I like the sharp contrast of monochromatic effect and the interplay of the various shades of the colour black on a white background."

-Jyoti Kalsi