Melodies plucked from a hallowed tradition

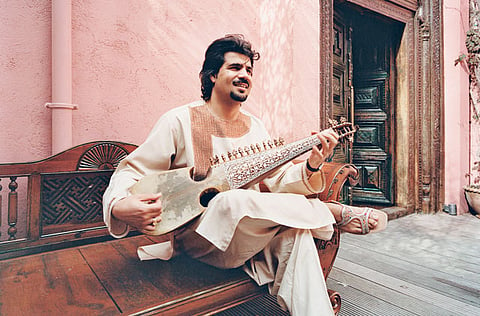

Afghan rubab virtuoso Humayon Sakhi will team up with percussionists Salar Nader and Abbos Kosimov to keep the Kabuli style of Indian raga performance alive

The phenomenon of call and response is pervasive in every sphere of human existence. Its transcendence in music points to something essential but vague. In a fiery drut section of a raga, three outstanding instrumentalists are set to strike the chords of this connotative philosophy with their rhythmic patterns and classical groove.

Plucking at the strings of his rubab with seemingly effortless ease, the greatest living exponent of the traditional Kabuli style of the Indian raga, Humayon Sakhi, will serenade a swirl of melodic colours and rhythms to a melodious jugalbandi with doyra player Abbos Kosimov and tabla player Salar Nader.

"It will be a memorable image of day and night," says Sakhi. To elaborate more would be an exaggeration as it is quite apparent what happens when artistes of the highest calibre create music that represents a confluence of cultural influences with instruments that bear rich historical references. However, the meditative mode of the sawaal-jawaab — the challenge of identical contours and same tempo — is expected to provide ample evidence that music is the language of the spirit, a road to dialogue.

"The rubab is the door to the soul," says Sakhi. "I'll never forget that spring day when I encountered the scintillating melody of the instrument. The endless plucking of the strings led me to a trance-like state without ever becoming repetitive. The purity of the sound awakened my spirit and sparked my interest and passion for many years to come. I was attained."

From Kabul to California, Sakhi is admired as a virtuoso of his generation, who has pushed the limits of the rubab. Born in Kabul in 1976, Sakhi was heir to one of Afghanistan's great musical dynasties. His father, Gulam Sakhi, was a student and brother-in-law of Ustad Mohammad Omar, a revered musician with a link to the origins of Afghan classical music.

Becoming the torchbearer of a tradition that stretches back to the mid-19th century was part of his curiosity and enthusiasm. Nevertheless, growing up in Kuchech Kharaba, the famous musicians' quarter in Kabul, Sakhi readily absorbed many musical styles — from Afghani classical music to Persian ghazals and Hindustani ragas and Asian cinema music and Western pop sounds.

The rubab boasts a complex scope as a culturally specific musical instrument. Originally Central Asian, the double-chambered lute is rooted in the raga tradition of North India. Though being the heart of Afghanistan's Pashtun klasik tradition, its music has strong stylistic links to Iran. When accompanied by the tabla, the sound's sophisticated rhythmic element seems to have drawn inspiration from older forms of Central and West Asian kettle and goblet drums.

When Sakhi settled in Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1992, because of the political unrest in his country, he was exposed to the rubab-playing of masters from Herat and other musical centres. "I played a mixture of ragas and songs," Sakhi recalls. "I earned a good income as an entertainer. I played on television and on the radio."

It was then he discovered the mystical versatility the rubab holds. The unofficial headquarters of Afghanistan's émigré music community in Peshawar was Khalil House, a modern apartment building where 30 to 40 bands established offices. Long hours and a spirit of camaraderie in Khalil House enabled him to maintain and further develop key musical skills.

"The people of Peshawar play the rubab in a very different way," Sakhi explains. "I introduced the Kabuli style to them. Traditionally, the rubab players didn't touch the instrument's sympathetic strings. But I used them a lot, in addition to the melody strings. Earlier players just picked down with the plectrum but I picked both up and down. I listened to a lot of different instruments, such as the music of violin, guitar and sitar. I wondered why I couldn't play the rubab using those techniques. It is not just an instrument to back up a singer. I discovered a complex picking style that uses rhythmic syncopation and playing off the beat."

Sakhi's artistry demonstrates the vastness of his traditional resources. He strives to maintain a link with his heritage by bridging the classical with the contemporary, simultaneously exploiting the many possibilities beyond the confines of tradition.

"Musicians always try to improve. We have different genres, such as folk, classical and modern, and each has its own pleasure, style and sound. When I mixed the rubab with other new elements, the outcome was very positive and joyous. ... Nevertheless, the rubab lives and will continue to have a place in my heart," he says. "A musician barred from [indulging in] his passion and talent will always be in a state of sorrow and unhappiness if it is caused by violence and aggravation. Every artiste has put in years of dedicated practice to pursue his or her dream. Forcibly taking it away from them is like caging a bird and cutting off its wings."

Perhaps the challenging circumstances in which he had to practise his art have drawn the artiste to explore universal themes in music. Unlike his contemporaries who returned to Afghanistan to rebuild their country after the fall of the Taliban, Sakhi is based in Fremont in the south-east San Francisco Bay Area, a city that claims the largest concentration of Afghans in the United States. He has founded a music school and resumed his recording and performing career, now working closely with another Kabuli master musician, tabla player Toryalai Hashimi.

They have gone beyond the Afghan community, recording their first album for the Smithsonian Folkways label in 2005 and touring internationally as part of the Music and Voices of Central Asia tour under the aegis of the Smithsonian and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Sakhi recently joined America's premier music ensemble Kronos Quartet and Azerbaijan's popular traditional singers Alim and Fargana Qasimov in the latest Smithsonian Folkways release Rainbow.

The title track, Rangin Kaman (‘rainbow' in Persian), was written by Sakhi especially for this project. "Colours are important to me in my composition," Sakhi reveals. "I fuse together different colours as a way of expressing hope for peace and harmony among different peoples and nations."

He also teamed up with Indian classical musician Rahul Sharma for In The Footsteps of Babur: Musical Encounters from the Lands of the Mughal, an album that explores the common ground in musical styles, sensibilities, and instruments from Central Asia, Afghanistan, and North India. Together with brilliant instrumentalists, they illuminate the musical legacy of the Mughal Empire, founded five centuries ago by the Emperor Babur.

According to Sakhi, the purpose of his music is to introduce listeners to the originality of the rubab's melody. With Afghan tabla player Nader and Uzbek master percussionist Kosimov, he says, "the chemistry has been positive, in fact awesome".

Primarily an instrumental technique, the sawaal-jawaab takes place between two artistes, with one musician challenging the other by playing a short musical phrase. The melodically and rhythmically challenging riff is answered by the other by producing identical notes in every detail.

The session goes on till the energy explodes and reaches a crescendo. The constant improvisation generates mathematical patterns which culminate in an ending known as tehai.

"We share a common heritage that comes from the cultures of the Silk Route, deeply connected through historical and artistic overlaps," says Kosimov. "We engage in friendly competition. But more importantly, we challenge each other to bring the best out of respective styles. That is why I believe art is the highest form of intelligence."

Kosimov will be playing his national instrument doyra, a flat, round drum made from horse skin, with metal shakers inside. "Uzbek culture and national identity is deeply rooted in its music and dance traditions. As such, the doyra has grown with the country over time and evolved to play a deeper role in reflecting Uzbek history, religion, heritage, and cultural traditions," says Kosimov.

So what would the artistes like the audience to take home with them? "The innocence and love that comes out during our performance," says Nader. "I hope it makes the audience feel hopeful for Afghanistan and its people as we are acting as cultural ambassadors through our music. We are doing our best to give the Afghan people a positive image around the world."

Artistry with threads

- 'The Art of the Afghan Rubab’ concert complements the ongoing exhibition titled 'The Story of Islamic Embroidery in Nomadic and Urban Traditions’.

- The show brings together more than 200 rare and majestic textiles, including a wealth of embroidery from Central Asia that help visitors explore the exchange of trade and culture across the Silk Route and beyond.

- These works, with their kaleidoscope of motifs and colours, create a form of abstract art and testify to the role of Islamic women in creating an artistic tradition of great significance and beauty.

- The works on display include embroidered garments and decorative objects dating from the 17th to the 20th century that illuminate how the magnificent tradition of embroidery was carried on by urban, rural and nomadic women and sustained regional, tribal and family identities through its integration in communal activities and how it evolved the encounter of different cultures.

- 'The Story of Islamic Embroidery in Nomadic and Urban Traditions’ is on until July 28 at Gallery One, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi.

Layla Haroon is a freelance writer based in Abu Dhabi.

The Art of the Afghan Rubab will be held on July 22 at Manarat Al Saadiyat, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox