June 28 1971, New York City; another humid day in the middle of a heatwave that had been pressing down on the city for weeks. The large crowd, attending the second annual gathering of the Italian-American Civil Rights League, didn't help matters. Up on the raised platform were the founders, waving to their supporters below; the press were given front-row access.

Among them was Jerome A Johnson, a young African-American from New Jersey. Adorned with his press credentials, there was nothing out of the ordinary as Johnson followed the league's founder around with a film camera. A female voice called out a greeting to the founder, at which point Johnson lowered his camera, pulled out a gun, and bada-bing! Three shots at close range to the head took down Mr Joe Colombo, founder of the Italian-American Civil Rights League, and crime boss of one of New York's infamous Five Families.

A few blocks away Director Francis Ford Coppola, a 31-year-old Italian-American, was filming the climactic scenes of a movie that would soon make Colombo's informal title an instantly recognisable term, transcending borders and ages, and bringing to mind a hundred classic phrases and images: The Godfather.

As well as winning the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1972, The Godfather also won Oscars for Marlon Brando as Best Actor and for Best Screenplay. In the decades that have passed, many of the other films that received nominations that year have, for the most part, passed from popular consciousness. But The Godfather and its sequels remain as alive and vibrant as it was upon its release in March of 1972, and the statement, "I'll make him an offer he can't refuse" still reverberates. Why has this film saga endured? Perhaps it's the film's close link to the secret society it was portraying.

Months prior to the hit, Colombo was sitting in producer Al Ruddy's office in a scene that would not have seemed out of place in the film. Colombo, as head of the league, had been outspoken in his disapproval of the movie. Publicly he spoke of the racist portrayal of Italian-Americans and lobbied local Italians into joining him in boycotting the movie's production. Behind the scenes, the studio was receiving daily bomb threats, and Paramount executives were receiving anonymous phone calls threatening them and their families' lives.

In a bold move Ruddy approached Colombo directly and invited him to read over the script. Colombo accepted. After making a show of it, Colombo, with two bodyguards at his side, and having read only the first page of the script, threw it on the desk: "I want any references of ‘Mafia' removed." Ruddy could not believe his luck, he knew that the script contained only one such reference. "That's OK with me," he said, shaking hands with the most powerful man in New York to seal the deal.

And that was that. Now that the mob had publicly blessed the movie, members began playing a role in it, not just in the extra parts a few landed but, more importantly, as models for the major actors. "It was like one happy family," said Ruddy. "All these guys loved the underworld characters, and obviously the underworld guys loved Hollywood." It was a match made in heaven.

The forging of this apparently unlikely relationship highlighted one of the deeper themes of the story Coppola wanted to tell. Upon reading the novel, The Godfather, Coppola, who worked closely with its author, Mario Puzo, on the screenplay, decided it should not simply be a film about organised crime, but a family chronicle - a metaphor for capitalism in America.

Two things quickly became apparent to Coppola: for the film to be authentic, it had to be a period piece, set in the 1940s, and it had to be filmed in New York City, the stomping ground of the Mafia.

Although Coppola used a variety of cinematic techniques (many harking back to earlier examples of American gangster films) in his exposition of narrative, including montage, and in The Godfather II, flashback, the film's power derives from a deceptively simple narrative structure: a tale of one family's rise and fall. This is one of the reasons it remains so popular: The tale of The Godfather, like the Mafia itself, is so American. And so is the story's eponymous hero, Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando). A man of morals, principle, and courage in a world sorely lacking - a man who stands throughout the film in stark contrast to the state.

It's worth noting that The Godfather was made and released in the middle of Richard Nixon's term in office. The public had become more than familiar with the notion of corrupt politicians playing in a corrupt state, a concept that remains as relevant for modern audiences across the globe today as it did in 1972.

Throughout the film, in contrast to the morality of the Godfather, we see the corruption of the state. In the wedding scene, very early in the film, we begin to see the relationship between the Don and the state when his consigliere Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall) tells him that a senator and some judges had called to apologise for not being there.

This is clarified a little later when Virgil ‘The Turk' Sollozzo (Al Lettieri), who wants Don to finance his drug business, tells him: "I need a man who has powerful friends…. I need, Don Corleone, those politicians that you carry in your pocket like so many nickels and dimes." And late in the film, Coppola speaks very specifically about the state during a conversation between Michael (Al Pacino) and Kay (Diane Keaton). Michael says that his father is "no different than any other powerful man, any man who's responsible for other people, like a senator or a president."

"You know how naïve you sound?" says Kay. "Senators and presidents don't have men killed." To which Michael replies: "Who's being naïve, Kay?" Unlike the state, the Don is not corrupt - violent, yes, but not corrupt. While he buys politicians, he himself cannot be bought. Law, however, tells us that since he uses violence he is therefore an evil man. But he is not. He's just a man who has refused to yield to the state, and uses violence with restraint.

This, then, is another reason why The Godfather endures: its main character is a true man; strong, brave, and principled enough to stand up to and defy the power of the state. He is, in short, the kind of man we all wish to be. This is what makes the subtle break-up of all he has built - his family - so very tragic.

Coppola's screenplay structure helps to highlight this downfall by bringing into focus the church, country, and ideas of hierarchy. Given the traditions of the gangster movie it's perhaps almost inevitable that their treatment should reflect ambiguity. As the film's narrative unfolds each of these symbols of authority systematically disintegrates.

"It may be the greatest family movie ever made," said Ruddy. "It's a great tragedy of a man and the son he worships, the son who embodied all the hopes he had for his future."

It endures because of the moments - intentional and accidental alike. Lenny Montana (Luca Brasi) caught on camera rehearsing his lines and messing them up in a way no trained actor could accomplish (both incorporated in the final cut of the movie); the discovery of the horse's head; when Michael realises it was his brother, Fredo (John Cazale); a young Vito (Robert De Niro) stalking Don Fanucci (Gastone Moschin) across the rooftops in one of the saga's few tracking shots; a phrase, not in the script, popping out of Sonny's (James Caan) mouth during a mocking retort after hearing his kid brother say he intended to assassinate his father's would-be killers: "What do you think this is, the army, where you shoot 'em a mile away? You gotta get up close, like this - and bada-bing!"

In the end, the mafia adopted it as their own, employing the term Puzo invented (the ‘Godfather'), and others such as the aforementioned ‘bada-bing'; as well as playing the movie's haunting theme music at their weddings, baptisms, and funerals. "It made our life seem honourable," Salvatore ‘Sammy the Bull' Gravano, of the Gambino crime family, later told The New York Times. The impact was no less great for Hollywood and the public: when the film opened across America it became the biggest-grossing film of its time, doing more business in six months than Gone with the Wind had done in more than 30 years.

With The Godfather, the blockbuster era had begun, and its creator was the last to know. "I had been so conditioned to think the film was bad - too dark, too long, too boring - that I didn't think it would have any success," said Coppola.

June 29, 1971, the day after Colombo's shooting, Ruddy was at the St Regis Hotel with Coppola, watching actor Richard Castellano (playing Clemenza) fire into an elevator full of Michael Corleone's enemies with a shotgun. It was a surreal and poignant moment for them both, Coppola turned to Ruddy and said: "Would you believe it? Before we started working on the film, we kept saying, ‘But these Mafia guys don't go around shooting each other any more...'"

Cinematography & lighting

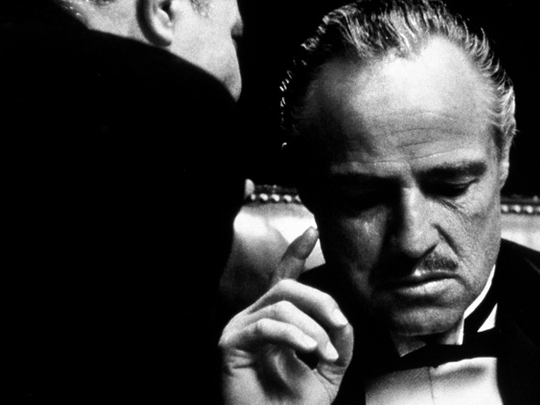

One of the distinctive features of Coppola's direction of the trilogy and especially the first two films is his use of set-piece mises-en-scène, which invariably help establish the family structure. Practically every shot from the film is framed in such a way that it could serve as a classical painting. Indeed very few camera moves and tracking shots (even exceptions of Part II and De Niro stalking local boss Fanucci were shot in such a way as to evoke a still image) were utilised. Coppola and Director of Photography Gordon Willis were not afraid at all of static shots.

The studio on the other hand, were.

Along with the shooting style they had a huge problem with the Willis' lighting: in an era when films were over-lit, Gordon Willis shot The Godfather in shadow and darkness, initially horrifying the studio executives but creating a new standard in cinematography. "I just kept doing what I felt was visually appropriate for the movie," says Willis. Coppola was fighting battles on all sides; his job wasn't really secure until the executives saw the masterly scene of Michael gunning down Sollozzo and McCluskey (Sterling Hayden).

Willis emphasised that the most important visual aspect of The Godfather was its colour structure. "It's yellow-red in much of the lighting as well as the lab work, and that ties all three films together," says Willis. "The repeatability of the visual structure really has to do with making the right choices. The initial choice is taste, and maintaining the look is craft. There's great elegance in simplicity. My choices in lighting and the overall color were designed to create a mythic, retrospective feel, [one] without clutter."

As for the studio heads nervousness at the time, Willis, who oversaw the restoration of the print for the Blu-Ray release, had this to say: "When people see things they don't understand, they become frightened, and the concept of what The Godfather is - or was - still eludes some people."

Actors considered

Vito Corleone: Burt Lancaster, Laurence Olivier, Ernest Borgnine, Richard Conte, Anthony Quinn, Carlo Ponti, or Danny Thomas

Michael Corleone: Robert Redford, Martin Sheen, Ryan O'Neal, David Carradine, Jack Nicholson, James Caan (who was actually cast at one point), and Warren Beatty.

Sonny Corleone: Carmine Caridi, Robert De Niro.