Today, a new film by the renowned Chinese director Zhang Yimou is being shown for the first time. The screening of The Flowers of War in a Hollywood cinema is the opening salvo of two months of hoopla and hype in the lead-up to the Oscars.

Meanwhile, at her home in Amman, Jordan, Palestinian filmmaker Annemarie Jacir is scraping together enough cash to put the finishing touches to her second feature, When I Saw You. No hoopla. No hype. She is editing the film on a personal computer and her chair is falling apart which, she says, is not good for her back. Far from finding a venue for its first showing, she still has to find a place to complete the sound work.

They are worlds apart — yet for the past year the two have been brought together by an innovative scheme in which emerging talents are teamed with luminaries of the arts world. The Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative has recruited the likes of Sir Peter Hall, Toni Morrison, David Hockney and Martin Scorsese to share their wisdom since the scheme was launched in 2002. This year, sculptor Anish Kapoor, musician Brian Eno and flamboyant theatre director Peter Sellars were among those taking part.

Jacir, 37, was chosen from a shortlist of three to pick up a skill or two from Zhang. As part of the initiative, she was flown to China, where the director was working on his film which tells the story of the Nanking Massacre of 1937 when 80,000 citizens were raped and many thousands killed by Japanese soldiers in a blood-crazed six-week period.

She marvelled at the sheer size of the enterprise; the set, the cranes, the huge cast, not to mention the marketing facilities and, of course, the budget. The Flowers of War, which has to be shown seven times in Los Angeles County, California, between now and the end of the year to qualify for an Academy Award, is estimated to have cost $90 million, while her budget crept to the $400,000 mark.

"His film is a small story within a huge historical event which is often denied. I relate to this as a Palestinian because much of our history is also denied. We are both telling stories about us, our people. We are both talking about injustice which is both personal and universal — that's the parallel," Jacir says.

For her, the work is inevitably informed by the plight of her state but, poignantly, it is overshadowed by a ban imposed on her by Israeli authorities four years ago, forcing her to live in Jordan, often apart from her husband, Ossama. He has now joined her, working as her producer and she jokes: "He is a master chef so I am lucky to have a producer like that to cook amazing meals for me. It feeds my soul."

There is nothing light-hearted about her work. "The film is about the stupidity of borders," she says. "They ruin the world."

She talks movingly about not being able to return home. "A short drive from Amman and I can see Palestine. Over the valley I see the hills, even recognise cities. My friends, my family and my apartment in Ramallah are there — but I can no longer reach them. Palestine is becoming a memory, and I struggle to hold the visuals, the reality of my life there, as close to me as I can. This is how When I Saw You was born — with the knowledge of being so close to home and yet getting there being an impossible dream."

"I have not been banned because of my filmmaking but because there is a silent Israeli policy which, in a random way, is excluding thousands of people," she says.

In the public talks Jacir joined at the Rolex gathering of mentors and protégés in New York last month, she came across as an intense, rather brave woman, who maintains her sense of humour.

She lived in Saudi Arabia until the age of 16 before going to the United States for her education. There was nothing in her childhood to show that a career in films beckoned. "There were only five tapes in the house — Star Trek; Pete's Dragon, an animated musical about an orphan boy and his magical dragon; Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; The Cat from Outer Space; and Fiddler on the Roof," she drolly recalls.

Considering its portrayal of a caricature Jewish father of five daughters, it is surprising that Fiddler on the Roof was the film she connected with the most. "I must have seen it 400 times," she says. "My father is the father in Fiddler on the Roof."

Jacir worked in films in Los Angeles before co-founding her company, Philistine Films. She has made documentaries on the refugee camps and is also the co-founder of the Dreams of a Nation project, dedicated to the promotion of Palestinian cinema. Three years ago, her first feature, Salt of This Sea, earned her an Oscar nomination for best foreign-language film. "When I finished it, I was depressed, so I needed to do something different," Jacir recalls. "I decided to set When I Saw You in 1967 after the Six Day War. For the Palestinians then, there was a great deal of hope and the country was not as isolated as it is today. People were more connected — with what was happening in, say, Vietnam, and in France with its social movements."

The film is about a mother and a son who are refugees in the Jerash camp, Jordan. They have been split up from the father by the war, and the boy is obsessed with finding him. He does not understand why they cannot simply walk back to their home. The 13-year-old, who is the star of the film, is also a refugee in real life. He was born in Jordan to refugee parents. Even his grandparents are refugees.

"We had to build a world for him before he could understand where he comes from," Jacir says. "We spent months — me, the boy and the woman who plays his mother — creating a life. What does he do after school? What does he eat? The relation with his father — does he work? I drew a picture of the house he might have lived in, the kitchen and every piece of furniture, so that I could say, ‘This is the place where the boy was brought up and is trying to get back to'."

The film had a big impact on the boy and his family. "When I was wrapping up on the final day, his father was on the sets, and he was bawling, really crying," she recalls. "He said, ‘All my life I have been trying to explain to my son what is Palestine, what is our history, and I can't figure out how to. I can't explain why I can't get across that valley to that place right over there and what the place means to me. Now because of this film he understands'." Overcome by the intensity of the moment, Jacir had started crying too.

Everything about making the film has been a challenge, something that Zhang, with such successes as Hero and House of Flying Daggers on his CV, no longer has to concern himself with. He was able to get Christian Bale to appear as the missionary who rescues Chinese schoolgirls and prostitutes from the Japanese, but Jacir had no established film actors to call on. She searched community centres, refugee camps and schools' drama departments and met about 200 boys before she found her "star", Mahmoud Asfa.

Then there is distribution, which is almost impossible without infrastructure or a network of cinemas. When she finished Salt of This Sea, which had been shot "guerrilla style" and subsequently banned in Palestine, she took it to the refugee camps and found that the "response was incredible".

Funding has been erratic. Despite a boost from the Tribeca Film Institute in New York and the offer of an editing studio from the organisers of the Thessaloniki, Greece, Film Festival, she admits she filmed knowing she did not have enough money for post-production work. Now she has private Arab investors who, she says, are relaxed if the project is not a commercial success.

"Maybe, at last, we have a support system," she says. "The film festivals in Dubai and Abu Dhabi are crucial because they are high-profile and attract big audiences.

"We need one good art house in every major city. The audience is there, it's a question of how to reach them. People go to the cinema in malls after shopping and they want easy watching. It's just so hard to break the hegemony of Hollywood and Bollywood."

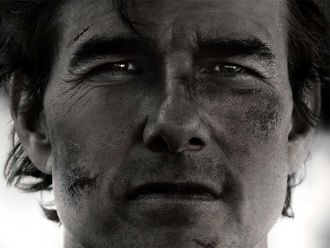

So there is an irony in her rubbing shoulders with Zhang, but he also struggled to be seen and heard when he started out. Zhang worked as a farmhand and sold his blood to buy his first camera. He was 25 when the Beijing Film Academy reopened in 1978 after the Cultural Revolution, and 27 when his photography portfolio won him a place in the department of cinematography.

"His budget was about 200 times bigger than mine; I shoot for five weeks, he shoots for five-and-a-half months. And he might have 100 takes for a scene, but for him, film is not about that — if you took everything away from him tomorrow, he would still make a fabulous film," Jacir says.

What did she learn from the great man? "He asked me to check that some books on shelves were right for the period but when the shot came up they were out of focus in the background." She laughs. "He taught me how important attention to detail is. He knows exactly what he wants. It's his intuition, and that's why he gets so obsessed with a shot that doesn't feel right," she says.

Zhang says: "I have travelled the same road as Annemarie and understand low-budget filmmaking. My advice to her is not to ever give up. Just wait for better times."

Jacir is not the type to give up. The road is open to her — professionally, at least. But as long as the border to her homeland is closed, those better times will remain elusive.

Richard Holledge is an independent writer based in London.