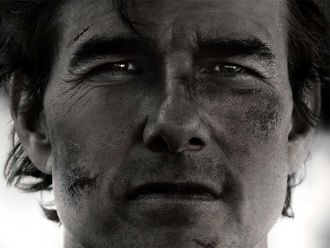

Tim Robbins has just made his debut album at the age of 51. He has also recently separated from his long-term partner, fellow movie star Susan Sarandon. So let's get this out of the way. Robbins is quietly insistent his music should not be considered a comment on his relationship.

"It's not a divorce album," he says firmly. "It's pre-divorce." He is not, apparently, inclined to expand on this. And given that he is 2m tall and looms over me with a gentle but nonetheless imposing authority, I am not entirely sure whether I should push this line of enquiry any further. Still, it does prompt the question, did it cause his divorce? Robbins guffaws, long and loud.

"Oh, that's funny," he says. "Uh, no, it didn't." Then he laughs some more but shakes his head, ruefully. "I'm not going to go there." Where he will go, however, is to talk about the idea of change, even so far as joking that he considered calling the album Mid-Life Crisis. "When you reach your mid-forties, it does put things into perspective." He recently moved from New York (where he grew up and where he lived with Sarandon for 21 years, raising two children) to Los Angeles. "I am in a completely different place, literally and figuratively."

He traces the roots of this change of direction back to a failed film project, when a story he had spent a long time writing and developing began to unravel on set in Portland, Oregon. "I got sabotaged by a financier, and everything began dissolving in front of me. I started thinking about things falling apart. You realise, of course, that nothing is owed to you, no matter who you are. Life is a series of consequences, and how they evolve is up to something other than your own will."

This led him to ask key life-changing questions: "What had I not done? What would I regret not doing?" His solution was to record an album of songs he has been writing all his adult life. "It was out of a dark place, that's how it came about. I knew I had to create something out of that."

There have always been a number of strings to Robbins' artistic bow. He is primarily known as an Oscar-winning actor, with roles in such highly regarded movies as Bull Durham, The Player, The Shawshank Redemption and Mystic River, but he is also a screenwriter and director (most famously of Dead Man Walking) and runs his own small theatre company, The Actors Gang. But it turns out he has been playing guitar and writing songs from long before any of that.

Robbins' father, Gilbert, was a member of the popular early-Sixties American folk band The Highwaymen. Robbins' brother David is a guitarist and film composer, and the two occasionally play together at charitable benefits. However, despite performing his own satirical songs in his movie of a folk-singing right-wing politician, Bob Roberts (1992), he previously resisted all offers from record companies. "I didn't have the desire to use my celebrity to become a faux rock-and-roller. What interests me is what's really necessary: is there something artistic that needs to be expressed?"

Robbins' skills as a guitarist are limited. His vocal range is fairly minimal. What he does have is the gift of the storyteller. Performing with an outstanding band assembled by iconoclastic producer Hal Wilner, Robbins' debut album is full of emotionally complex and morally ambiguous narratives set to woozy, dreamy, American soundscapes.

One song, Time to Kill, is delivered as the anguished confession of an Iraq combat veteran ridden with guilt for the death of innocent children. "I can't stand hotel rooms, so wherever I'm working, I try to go out, bring my guitar with me and find places to play. Inevitably, at any haunt, an Iraq veteran would come up to me.

"These guys would really open up and just spill. I think the reason they were picking me was that I was known to be against this war. A guy in Colorado told me he couldn't tell his family what went on over there because they held him up to be a hero. I said, ‘Why not talk with guys you went over with?' He said, ‘They're all dead.' It was heartbreaking. I went home that night and wrote the song. He needed his story to be told."

Robbins is a thoughtful character, who speaks in long, sprawling quotes, phrasing and rephrasing and refining key points. An outspoken critic of former US President George W Bush and the rush to war in Iraq, he has a reputation as a political activist, although he is uncomfortable with the notion. "If you look at the work I've done, I've given humanity to murderers and torturers. It's not my job to make dogma when telling a story. The best we can do is to tell each side fairly and realise that life is complicated."

I would still say that Robbins is a better actor than musician, but his ambivalence towards the profession is tangible. "It's not fun for me to be in a bad movie at this point in my life. I turn down a lot of stuff... I want to do things that I'm going to be proud of, that are going to be challenging, parts that I haven't played before. So I work less and less in movies."

The experience of making his debut album seems to have given him a glimpse of a new kind of creative freedom. "It took me five years to put together Bob Roberts, six years for The Cradle Will Rock. Part of the whole challenge of directing movies is raising the finance. How do you get that done so it doesn't drive you crazy or make a compromise that kills your film? There are all these roadblocks, obstacles, for every project I've ever done... But I can write a song and go and play it. I don't have to ask anyone's permission. I don't need a budget, I just thought of it a few days ago, here it is, do you like it?" So, he has broken up with his partner, moved to California, got rid of his TV and recorded an album. Is Tim Robbins over his mid-life crisis, I wonder. "I would hope that existential nightmare is over," he laughs. "I think it is. But we'll see. I'm just happy to have avoided the red Corvette sports car."