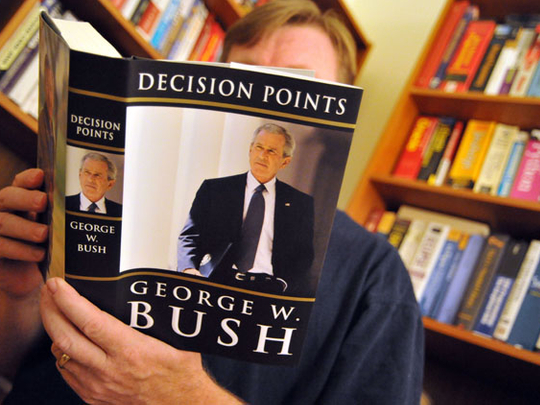

On the morning of September 11, 2001, as the scale of the airborne terror attack on the US became clear, George W. Bush gave US military pilots authority to shoot down passenger jets that did not respond to calls to land. It was a momentous ruling that could have resulted in hundreds of civilian deaths. "I had just taken my first decision as a wartime commander in chief," Bush writes in Decision Points, his memoir.

For Bush, 9/11 was a personal vindication, the moment his presidency became exempt from ordinary, civilian criticism. He frequently refers to himself as a war leader. The predecessor he cites most often, apart from his father, is Abraham Lincoln. The "war on terror", he claims, was a campaign of existential magnitude for the US, akin to the civil war. Most presidents get involved in military conflict, but Bush imagines himself in a more exclusive club: Abe, FDR, Dubya.

It is not just a metaphorical leap. The assumption of wartime duties gives the president extra authority under the constitution, and this is central to Bush's defence against the charge that he trampled traditional American values and freedoms in pursuit of homeland security. Military emergency makes rampant executive power expedient: the approval of water-boarding; the surveillance of civilian communications; the invasion of Iraq. In each case, the commander in chief thought it better to be maverick and safe than multilateral and sorry. The absence of another terrorist assault on American soil, says Bush, is legacy enough.

Decision Points doesn't try to position Bush's presidency in a global or historical context. It is a sequence of episodes that are supposed to reveal the character of the man in the Oval Office. There is no ambition to be thorough. Bush is highly selective, lavishing himself with praise for achievements (African aid programmes, for example) and doggedly reallocating blame for things that went wrong, such as the handling of hurricane Katrina. (It was the Democrat governor of Louisiana's fault.) He is prepared to admit mistakes, but only on matters of presentation. "Bring ‘em on!" he concedes, was not a suitable response to Iraqi insurgent attacks. The rally in military fatigues under a banner reading "Mission Accomplished", when Iraq was still ablaze, was an example of "stagecraft gone awry".

Mindful, perhaps, of his image as a zealot, Bush portrays his decision-making as studiously pragmatic. He remembers soliciting advice from all quarters and selecting the best option on the menu. The president came into office with a set of conservative convictions, formed in the 70s and largely undisturbed thereafter. Bush describes his political epiphany in reaction to the Carter administration: "I worried about America drifting left, toward a version of welfare-state Europe, where central government planning crowded out free enterprise. I wanted to do something about it." That makes an intriguing comparison with his recollection of the assassinations, a decade earlier, of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King in his senior college year, which provoke only a feeling that "everything was coming unglued".

He was too busy leading pitch invasions at football games to be political.

Perhaps he sincerely believes he is a self-made man. There is no reason to expect him to know himself; he comes across as a woeful judge of character. He thinks he has made a profound connection with Vladimir Putin because they bond over the Russian leader's fondness for a religious artefact. He attributes a breakthrough in negotiations with a Saudi prince to a shared interest in farming. He is crestfallen when his fair-weather buddies let him down. Bush's deeply personal approach to alliances reflects a wider void in strategic thinking. He seems to be genuinely incapable of imagining the world as it appears to a non-American. His chapter on the "Freedom Agenda" the doctrine that US power should be used to prise open markets and political systems alike skims across the surface of global issues without focus.

Likewise, the treatment of the credit crunch lacks analytical insight. Bush's accounts of governing through war and natural disaster are never ele-gant, but they convey a sense of drama and urgency. The narrative flow dries up completely when he gets to the biggest economic events of our time. The dialogue reads like a lazy TV script. "We don't have time to worry about politics," Bush has the hero, himself, say. "Let's figure out the right thing to do and do it!" There is no sense of historical moment. That is probably because the financial crisis doesn't lend itself to exposition in terms of Bush's personal morality. It required technical responses that are not easily turned into the fervent prayers that punctuate deliberations over Iraq and Afghanistan.

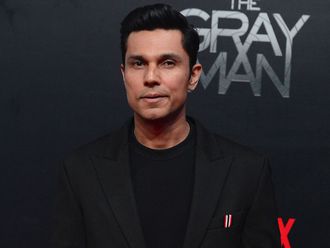

Decision Points by George W. Bush, Crown, 512 pages, $35