For 15 weeks during the Fall of 2007, 27-year-old photography student Al Moutasim Salem Al Maskery lived with about 100 fishermen in their makeshift village on Jumeirah Beach for his photo documentary class at the American University in Dubai (AUD).

Two years on, the Omani student is all set to wrap up the experience in a book.

“It was like [documenting] the ‘haves' and the ‘have-nots' in the same area,'' he said, referring to the village – the size of about six football fields and bound by the Dubai Offshore Sailing Club to the east, Jumeirah Beach and Burj Al Arab to the west and Umm Suqeim and Jumeirah Beach road to the south.

Al Maskery said at first the fishermen would either shy away or they would call their friends and pose for group pictures.

“So I started going there with just my tape recorder and I began talking to them to get to know them. I didn't speak Hindi or Urdu so I used a combination of Arabic, English and sign language.

“It was almost one month until they got used to me and the camera. After that they wouldn't even notice me. I even walked into the showers with my camera and nobody cared,'' he said.

Making do with less

Al Maskery was astounded by the fishermen's ingenuity.

“They build themselves makeshift lodgings from whatever scraps they can find.

“Their kitchen was built inside a wardrobe.''

Some fishermen even lived in large fish traps which they covered with blankets, rugs and tarp to make it a bit more comfortable, he said. “They would use everything; they would interlock rope that fastened their make-shift rooms because tying knots would waste too much rope.

“My teacher wanted me to take more photographs and focus on one subject, a narrative. I looked around and found something that they all had in common – a fisherman who was also the chef. So I decided to follow the fisherman-chef, as I called him, around for three months. His name was Raj and we became friends.

“He was one of the influential men in the village.''

Multi-tasking

In addition to fishing, the fisherman-chef also ran a kind of café. “I would usually eat with them; it was all South Indian food and it was very spicy. It hit me pretty bad. But I didn't care. ''

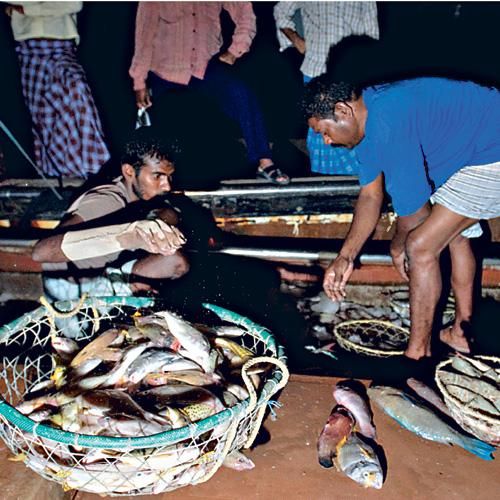

Al Maskery spent most nights in his car. At times, he'd stay up late to wait for the dhows to return with their catch.

Bartering is also part of life at the village, Al Maskery explained, as cash is not something they had very much of. “If someone had a radio or a TV that was nice, they might trade for it.''

Sadly, though, due to all the dredging and land reclamation projects, the fishermen are losing their livelihood.

Fishing spots

“In winter the fish come to shallow waters, but because they are not allowed to fish around The Palm and all the man-made islands, the fishermen are losing most of the good fishing spots. In summer the water is too warm so the fish go out to the deeper waters where only the larger dhows can reach,'' said Al Maskery.

He described the fishermen's lives as simple but complicated.

Although they live a simple life, they are “technically not allowed to live there'' and the rooms they have been given are actually store rooms for their gear, he added.

Living on the beach

“They have labour camps, but the camps are too far and it takes too long to get there and back and you need transportation and that's expensive. Besides, if they go to the camp, what time are they going to come back in the morning to catch the boat? So they just live there on the beach. It's easier,'' explained Al Maskery.

“Most of them go home once every two or three years. That's how often they get to see their wives and kids.

“Don't get me wrong. I don't pity them, I don't feel sorry for them at all. They have better mobile phones than I do,'' he joked.

Cameroon calling

Al Maskery is currently working on a project about children with disabilities. He also plans to go to Cameroon and take pictures of the children there. “I hope to be able to release a book for the Cameroonian children as well, with all the proceeds going towards their medication.''