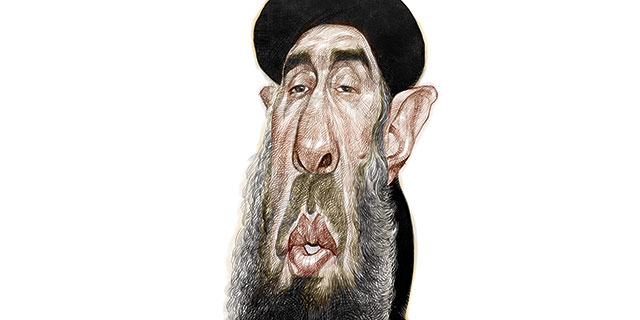

Former mujahideen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar is one of the most controversial figures in modern Afghan history. A former prime minister, he is remembered chiefly for his role in the bloody civil war of the 1990s.

In 2003, the US state department designated him a terrorist, accusing him of taking part in and supporting attacks by Al Qaida and the Taliban.

Observers say his willingness about four years ago to hold talks with the Afghan authorities was significant as it was expected to put pressure on the Taliban to also start reaching out to the government.

Hekmatyar was born in 1947 in Imam Sahib District of the Kunduz province, northern Afghanistan.

His mujahideen faction, the Hezb-e-Islami, was one of the groups which helped end the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

For a majority of Afghans, he was one of the heroes of that struggle.

But in the free-for-all that followed in the early 1990s, his group of ultra-conservative Sunni Muslim Pashtuns clashed violently with other mujahideen factions in the struggle for control of the capital, Kabul.

The Hezb-e-Islami was blamed for much of the terrible death and destruction of that period, which led many ordinary Afghans to welcome the emergence of the Taliban in 1996.

The civil war also led to Hekmatyar’s fall from grace — he quickly became one of the most reviled men in the country.

For some time, Hekmatyar himself enjoyed considerable support from Pakistan. But eventually Islamabad turned against him, preferring to give full support to the Taliban instead.

So like the other mujahideen factions, Hekmatyar and his men were forced to flee Kabul when the Taliban swept into power in 1996.

Wild card

He ended up being given refuge in Tehran, where he lived a quiet life, waiting for his fortunes to change.

The Iranians may have regarded him as a potentially useful Pashtun card to have up their sleeve, but he turned out to be too much of a wild card for them.

His vocal opposition both to the Americans and to the new regime of President Hamid Karzai was an embarrassment to the Iranian government, which threw its official weight behind Karzai.

In February 2002, the Iranian authorities expelled Hekmatyar and closed down the offices of his Hezb-e-Islami in Tehran.

They accused him of abusing Iranian hospitality with his comments vowing to fight the Karzai administration.

He returned to an undisclosed location in Afghanistan following threats by the Afghan government to arrest him and try him for war crimes.

In March of the same year he offered an olive branch to Karzai.

A spokesman for Hezb-e-Islami in Pakistan said Hekmatyar was now giving full support to the Karzai administration, although the warlord’s whereabouts remained a mystery.

Missile attack

Soon after, however, the Afghan administration arrested 160 people in Kabul in a suspected anti-government plot.

The government said the detainees had been conspiring to plant bombs in Kabul and that most were members of Hezb-e-Islami.

Hekmatyar remained elusive. In May 2002, the CIA reportedly spotted him in the Shegal Gorge, near Kabul, and tried to kill him with a missile from an unmanned spy plane. It missed.

The US continued to tighten the screw and was reportedly behind the arrest in Islamabad in October of Hekmatyar’s son, Ghairat Baheer.

Hekmatyar’s response was defiance. At the end of that year, he warned that a holy war would be stepped up against international troops in Afghanistan.

His message was distributed along the Afghan-Pakistan border to drum up recruits.

The message read: “Hezb-e-Islami will fight our jihad until foreign troops are gone from Afghanistan and Afghans have set up an Islamic government.”

Following that, Hekmatyar has slowly and steadily rebuilt his power base, especially in eastern Afghanistan.

He also continued to reiterate his ties to Al Qaida and the Taliban.

In a 2006 interview, he claimed his fighters had helped Osama Bin Laden escape from Tora Bora.

His insurgents were considered to be strongest around Kunar and Nagarhar.

They were also involved in some audacious attacks in Kabul, including an attempt on the life of Karzai in April 2008.

Surprisingly, Karzai personally owes Hekmatyar — in a tale which must be one of the bizarre episodes of Afghan politics. During the 1990s factional war, then a relatively unknown diplomat, Karzai was arrested and beaten up by the Northern Alliance for his efforts to mediate the return of Hekmatyar, who was holed up outside the city. The future president escaped jail in Kabul in a vehicle provided by Hekmatyar.

Independent analysts say Hekmatyar is one of the three most important insurgent leaders, along with Mullah Omar and another Taliban leader, Sirajuddin Haqqani.

Today, it remains unclear how much of the insurgency in Afghanistan is made up from Hekmatyar’s Hizb-e-Islami, partially because, despite his public animosity with the Taliban, the lines between his followers and those of the Taliban remain blurred. During his years in Iran, many of his followers joined the ranks of the Taliban government as, ultimately, they both shared the goal of a strictly Islamic government.

A prolific writer, Hekmatyar, despite rarely ceasing to fight, has managed to publish more than 60 books, mostly religious and political analysis. His rhetorical command is apparent, as in this excerpt in one of his letters: “We need to show the Americans that our patience is high, our stamina is strong, and that we can travel the dark nights. That if you can fight in foreign lands, how can we not fight in our own country? If your mercenary soldiers come from thousands of miles away to fight in our narrow valleys, is our back broken not to defend our homeland? You fight for my imprisonment, and I fight for my freedom.”

Source: BBC and Aljazeera.com

This column aims to profile personalities who made the news once but have now faded from the spotlight.

What he said:

The foreign forces have failed and the situation is worsening by the day. We might face a dreadful situation after 2014 which no one could have anticipated

It seems that some British authorities still dream about the times of the eighteenth and nineteenth century and they want their ambassador to be treated like a viceroy

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have proved that Britain has to go and take part instead in proxy wars – and this is what she cannot afford even for a short space of time