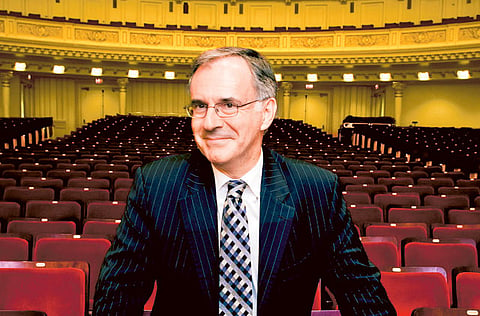

Sir Clive Gillinson on a mission to groom young musicians

Musician is reaching out to music communities far and wide

One would think growing up in a musical household would make a person passionate about music and encourage them to pursue it as a profession. But for Sir Clive Gillinson, CBE, that almost did not happen.

“I originally had the choice between mathematics and music, two subjects I love. My mother was a musician, and in those days in Britain, the men got all the jobs. So, [while] she was better than most of the men, it was actually a very different profession,” Gillinson said. His mother was a professional cellist while his father, a businessman, wrote and painted whenever he could.

“She suggested to me to take music up as a hobby and not as a profession, so I went to university, started studying mathematics and knew immediately that I had made a mistake, that music had to be my life.”

That led Gillinson to join the Royal Academy of Music in London before joining the London Symphony Orchestra’s cello section.

“It was a very exciting time … we moved into a new venue in London — a new hall had been built — and the management completely misjudged how to [organise] programmes [for] it, which led to a lot of financial problems … we were on the verge of bankruptcy. So, they were sacked. When they tried to look for a manager, they could not find anyone who wanted the job, so they decided to find someone from the orchestra to fill in the spot while they looked for a real manager,” Gillinson said.

“For whatever reason, I was chosen, and after three months they offered me the job. At first, I said no for two reasons. The first was that after three months you have no idea if I was the right person and also, I was not sure if I wanted to stay in this [position]. So, I told them to keep my [place] in the cello section open until the end of the year … a year later, they offered me the job again and I discovered that until I got into management, it was the last thing I was interested in or what I wanted to do,” he added, laughingly.

Twenty-one years later, in 2004, the orchestra’s then managing director was approached by the prestigious Carnegie Hall for the post of executive and artistic director.

“I had never thought about looking for another job but then when I got the call … it was a great opportunity and so I moved to New York,” Gillinson said.

Carnegie Hall boasts a long history and is one of the most prestigious concert venues in the United States. Through an in-house artistic programming department, it hosts about 250 performances each year. The main recital hall, which seats almost 3,000 people, was home to the New York Philharmonic Orchestra from 1892 until 1962. The second hall seats 599 and was refurbished and renamed the Zankel Hall in 2003. The Weill Recital Hall is named after Sanford Weill, the present chairman of Carnegie Hall’s board. The 268-seater is also home to the Weill Music Institute, which develops and implements Carnegie Hall’s music education programmes and educational initiatives.

“Among the many interviews that took place after the news was announced, I received a phone call from a representative of the Bangalore Times. You see, I was born there but my family left when I was only 3 months old ... the representative said that they wanted to do a front page spread with the headline Bangalore Boy Takes Over Carnegie Hall. When I explained that I had no knowledge of the city, having left when I was a baby, he said, ‘We do not care; we will take credit for it anyway!’” Gillinson said.

Musicians without borders

Since becoming the Hall’s executive and artistic director, Gillinson, who was knighted in 2005, formed many cultural partnerships, including a bilateral agreement with the Abu Dhabi Music and Arts Foundation (Admaf) in 2011.

As part of this cultural partnership, members of Carnegie Hall alumni, called the Declassified Ensemble, have been leading various school workshops during the ongoing Abu Dhabi Festival (March 3-31) and were part of a special performance with school pupils during the festival’s annual Young Artists Day.

“We work with people all around the world. This is, in a sense, all we are doing — making a connection here and the connection is to introduce the alumni to the festival,” Gillinson said. “We also have an exchange programme where we bring musicians to New York. We haven’t received any Emiratis yet, but that is the good thing about building a relationship such as this one with Admaf. It opens doors for opportunities for all.”

He also said that their participation is a part of the Hall’s mandate to give back to the community, whether in New York or elsewhere, no strings attached.

“We tend not to do quid pro quo. We do not say, if you take this, we will take that. Everyone gets to choose their own programming and it is never good if you do things on a trading basis,” Gillinson explained.

“We will not do exchanges or trades because we do not think that’s the right idea for anybody. Each person must choose what they want to have that complements the programme and what they are trying to create. The minute you start doing exchanges or trades, you have to do your programme around the fact that they want to do it like that when, really, you should be conceiving your programme as a whole.”

Receive and give

One outcome of this passion for musical education and a community of musicians was the creation of The Academy with The Juilliard School, and the Weill Music Institute in partnership with the New York City Department of Education. The two-year programme prepares young professional musicians for careers that combine musical excellence with teaching, community outreach, advocacy, and leadership.

“I’m very proud that we were able to create this programme. There’s no reason why someone cannot do something like The Academy in other countries. It does not have to be about classical music and it is not about classical music, it’s simply about music,” he said. “If someone wants to train the best young musicians, it is a very replicable model and it would be great if people did it elsewhere. At the moment no one has because you need a lot of resources, because there is so much training and it is very demanding putting a course like that together. But I think, like everything you create, once it is done, it has its own grand plan.”

Gillinson spoke about The Academy during a special lecture for students at Zayed University on March 10 as part of the 2013 Abu Dhabi Festival’s educational programme.

“I discussed the concept behind it to Hoda Al Kamis Kanoo (Admaf’s founder) and she said she would love to have something similar in Abu Dhabi. It is one of those things that has acquired a life of its own, and something like that, you should allow it to live,” he said.

Gillinson also spoke proudly of the establishment of the US National Youth Orchestra, which is the first programme that unites young musicians from across America. It is set to begin in the summer of 2013.

“They will not only be brought together with professional musicians but will also be given an opportunity to perform in the US as well as international locations such as Moscow, St Petersburg, London and China in the first two years. In the third year, I would love to bring them to this region to perform,” he said.

As for other projects that are on the horizon, Gillinson said, “For the next stage for Carnegie Hall, the biggest single thing that I have identified is to continue building our educational programmes.

“At present, we are helping an average of 400,000 pupils and we have 700,000 audience members every year. We are always searching for ways to share this with the world in one way or another. Everything we are doing is about how we can make the greatest contribution to people’s lives, in America and around the world, through our existing partnerships and new ones.”

Nathalie Farah is a writer based in Abu Dhabi.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox