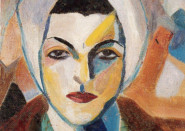

If ever there was an extraordinary artist denied honour in her own land it is Lebanon’s Saloua Raouda Choucair.

She should have been feted as perhaps the first abstract modern artist in Lebanon and even the Arab world, but her tragedy is that she was in the wrong place at the wrong time. She was a woman when female artists were rare, a Druze — which meant she was ostracised by those of other faiths — and she was caught up in the violence that beset Beirut between 1975-90, as one of her paintings, ripped by a bomb explosion at her family home, testifies.

Her art did not fit into the cultural establishment’s idea of modern art that referenced Lebanese tradition. What the critics wanted were subjects such as landscapes by the likes of Omar Onsi and Mustafa Faroukh that could clearly be rooted in a particular place or a moment.

At an exhibition in Paris the Lebanese ambassador to France said disparagingly: “Your work is curious Miss Raouda. Have you not done any Lebanese work for us?”

But now an exhibition at London’s Tate Modern Gallery is giving her the recognition she deserves — as an important figure in the history of modernism.

There is something painfully poignant about this moment of acclamation. Once a forceful feminist who brooked no argument, Choucair, at 97, is too infirm to fully appreciate that, at last, the international recognition she so merited — and craved — has been accorded her.

It should have been so different. In the late 1940s the aspiring young artist arrived in Paris to soak up the city’s bracing postwar art scene. She worked with the abstract artist Fernand Léger and studied the work of architect Le Corbusier, travelling to Marseilles to admire his huge housing development L’Unité d’Habitation.

In 1951 she returned to her homeland, where she produced works of abstraction in both sculpture and painting, using some of those Western lessons and her own unique interpretation of the principles of Islamic art with which she had grown up.

Had she stayed in Paris it is likely her reputation would have been assured, but in Lebanon her distinctive voice went largely unrecognised: she was rarely given the opportunity to hold exhibitions and sold very little.

But as her daughter, Hala Schoukair, who has dedicated much of her life to run the foundation which nurtures her mother’s work, says: “She was an avant-garde who was inspired by the principles of Islamic art, but without any visual references to what people were accustomed to seeing in that art.

“Her style is pure abstraction of form and line, just like a mathematical equation, without any references. It is an intellectual abstraction based on the idea that what preoccupied Arab philosophers and architects in the new spirit of Islam at that time was to represent God as infinity — with no beginning and no end. So this was reflected in the lines that they used in adorning mosques and in their writing. There was no correlation to calligraphy or Arab-esque patterns.

“She vehemently rejected the notion held by some about Islamic art being merely decorative, and inferior to others. Therefore my mother was often misunderstood, pushed aside, ignored, and left to be on her own.

“When I was growing up I started feeling my mother’s frustrations and became aware of how she was abused by the people in power, who would not give her a chance to flourish with her art. She was always complaining about somebody doing this thing or that to her, to the point that I, too, started to resent her. I could not bear her pain. I don’t think she realised that I was not a tough cookie like her. She kept on fighting and believing totally in her art.

“It was like a mission, and she never stopped creating. She thought her art, style and purpose were very important. She enjoyed it and defended her ideas by all means.”

The Tate show’s curator, Jessica Morgan, who knew little, if anything, of her subject, says: “I came across her work by happenstance when I was in Beirut visiting a gallery and on a shelf was this quite remarkable sculpture by Saloua Choucair. I went to her apartment, which was an incredible experience because everything — her work from the past five or six decades — was there.”

“What’s really rather tragic is that she is 97 and for almost ten years now she has been in a drastic state of decline. She doesn’t recognise her daughter and she has no sense of what’s going on and no idea of this belated recognition.

“Her daughter, who is in her fifties, told me that throughout her life her mother was always saying, ‘When are they coming?’, because she was really aware of the fact that what she was doing was good.”

The exhibition brings together more than 100 of her paintings and sculptures and reveals a technique that used a fascinating combination of mathematics, science and architecture, along with her instinctive understanding of Islamic forms.

Divided into eight more or less chronological sections, the show moves through all of Choucair’s major phases — from her delicate drawings and luminous gouaches to her stacked and interlocking sculptures and her wild experiments with centrifugal tension made of stainless steel, Plexiglas and nylon thread.

Along with Corbusier she was influenced by what she saw on a trip to Egypt in the 1940s — its ancient architecture and the modular forms.

Morgan explains: “The dynamism in her work comes from bringing together Islamic abstraction — which, after all, has centuries and centuries of history, compared with the 40-odd years of Western abstraction — and the abstract art she discovered in Paris. She made a forceful argument that these two are closely related but she wanted Islamic abstraction to be understood not as purely an exposure to Western abstraction.”

She virtually gave up painting in the 1960s to concentrate on her sculptures but the mathematical and architectural techniques were not dissimilar. She would divide her paintings into squares, halving and quartering, before working, and she used a similar method with her sculptures that she made out of stone, plastic and glass fibre. Her most characteristic sculptures are her interlocking units such as Infinite Structure (1963-65), which can be taken apart to leave individual pieces standing alone. They are a direct reference to Islamic Sufi poetry in which every stanza is considered to be a unique entity.

“She was completely taken with the idea of the unit — the blocks linking together, but also linking to Islamic architecture and indeed early modernist architecture which she saw in her travels,” Morgan says. “She was very broad-minded — that’s what makes her unique and fascinating.”

How important is she? “Because of her lack of exposure she has not played the role she should have,” Morgan says. “There is also the problem, which is not only of Lebanon, that because of the years of conflict there is an unnatural break between generations.

“There has been no easy flow between the different generations. Most art scenes are generated by a conversation in which you react to and develop with the help of each other, but in many parts of the Middle East that was not possible because of politics.

“I think, now, she is beginning to be much better understood as a very significant figure in the Middle East.”

“People did not really understand her art,” says her daughter, for whom the exhibition is a “bittersweet” moment: “But she kept on fighting and believing totally in her work. It was like a mission. Later she won some respect, which helped heal some of her wounds, but her ambition was much greater than that. She could not realise all her dreams.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

Saloua Raoud Choucar is on at Tate Modern, London, until October 20.