The Misunderstood Ally

By Faraz Inam,

Strand Publishing UK, 378 pages, $16

Pakistani author Faraz Inam’s attempt to portray his country’s security predicaments could be best described as an amateur but grudgingly praiseworthy effort. While “The Misunderstood Ally” has all the ingredients — terrorists, suicide bombings, brave army officers, a beautiful special agent, dangerous terrain (it can’t get more dangerous than FATA — Pakistan’s tribal belt bordering Afghanistan) that would make a thrilling copy — it fails to impact.

Despite his note imploring readers to understand the perspectives of the two sides, in this case, his native country Pakistan and its ally in the war on terror, the United States, Inam, in striving to present each, struggles to maintain a balance, often slipping into a laboriously constructed detachment that does not help the narrative in any way.

It may have been better for the author to take sides in this case and invest more in the three protagonists. The narrative falls short of uplifting the characters, which fail to evoke sympathy where needed and makes them instead appear more like caricatures. For one, the author has tried to condense an array of issues that may have fared better in a work of longer length. In any case the book’s message is loud and clear.

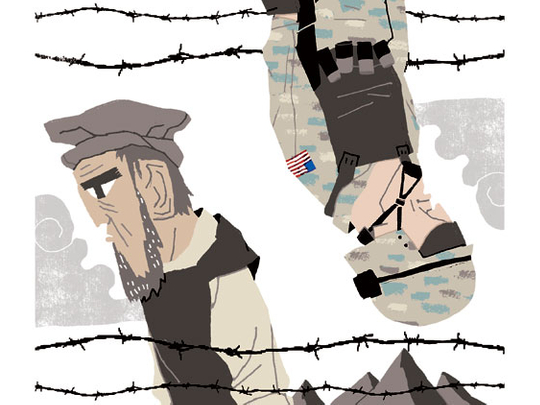

The relationship between the two allies in the war on terror is the theme of this novel. It makes use of three protagonists representing Pakistan’s armed forces, the US government and the Taliban. The rest of the supporting cast represent varying shades of the civilian life, lending an insight into the mindset of the type they are intended to portray. The core issues of mistrust and ownership of responsibility for the present state of affairs span the entire novel.

The author’s background and his knowledge of the armed forces personnel, their families’ routine and activities are apparent as the book offers an interesting glimpse into the life of the “other civilians” related to the officers in the armed forces. The only protagonist that has been drawn in flesh and blood is Lieutenant- Colonel Dhilawar Jahangiri, who wears his patriotism like a halo. His unflinching sense of duty is jolted when he faces a personal loss but the author manages to steer him clear and help him rise above the odds and acquit himself. On the other hand, the Afghan militant Baaz Jan has not been treated equally, a pity, since his character had much potential. Whereas Samantha Albright, a US special agent, leaves one with a wooden impression. The author’s unfinished treatment of Samantha, and depiction of personality traits that are chiefly “coldness” and a zeal to kill as many enemy combatants as possible for the sake of her country, is tedious. Humanising the ice maiden a’la killing machine whose readiness to fall into the arms of a mysterious and handsome Pashtun belies the persona the author has constructed. If Samantha is a living woman who thaws in the terrain where she is programmed to go for the kill, the author could have invested more in shedding some of her robotic layers during the course of the novel. The showcasing of her inner woman and the surfacing of a need to trust and love another human being, in this case, the mysterious Bilal Khattak, contradicts the impression created earlier.

Bilal, whose character and role in the novel could have been elaborated, fails to imbue the novel with more life and only speeds up things to a climax.

Despite its obvious flaws “The Misunderstood Ally” has some redeeming points. There is the chasm of culture, ideals and overriding suspicion between Pakistan, the militants and the United States. The underlying discourse reveals alternate themes embodied in the protagonists, whether it is the Afghan militants’ power struggle with Al Qaida in the insurgency; the grudge harboured by the Americans for Pakistan’s lack of gratitude for the billions of dollars worth of aid and refusal to abide by the rules of the game; or the Pakistanis’ frustration stemming from a collapse of the system and proliferation of militancy because of the Afghan war.

Depiction of the drone strikes and the suicide bombing may seem far-fetched but these are realities that millions have to live with and can probably relate to. While Inam packages drones, bombs, militancy, patriotism (both of Pakistan and the United States) and relationships, it is a fumbling attempt that could have been improved. Inam’s theatrical rendition of situations, whether it is the tense meeting between Baaz Jan and Al Qaida militants, or the suicide bombing at the cantonment, can be excused because of the quasi-war and the almost surreal environment prevailing in the country.

But since this is a debut work of fiction any shortcomings should be excused and it should be read in the spirit of understanding alternative perspectives and impact of terrorism on the people, whether it is army officers or civilians.