When the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge went on their tour of Asia and the South Pacific last year photographers from all newspapers in the United Kingdom, the international agencies, not to mention the TV camera crews, were on hand to record their every public moment.

But in 1862 when the 20-year-old heir to the throne, Prince Bertie, arrived in Cairo at the start of a lengthy Middle East tour it was the first time an official photographer had accompanied a royal party. He was 46-year-old Francis Bedford who had established himself as an accomplished lithographer but had embraced the new fashion in photography with enthusiasm and some success.

His landscape photographs had caught the eye of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, who were keen supporters of the new art form and who, in 1854, commissioned Bedford to photograph works in the Royal Collection. In 1857 the Queen commissioned Bedford secretly to take 60 views of Prince Albert’s home in Coburg, Bavaria, as a surprise birthday present.

Such was his esteem with the royal family that he was “one of only eight gentlemen” invited to join the Prince of Wales (the future king Edward VII of Great Britain) on the four-month tour.

The result can be seen in “Cairo to Constantinople: Early Photographs of the Middle East from the Royal Collection” in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, which recaptures the royal progress through Bedford’s lens.

He took about 210 photographs on the trip and they offer a fascinating glimpse, not just of the royal entourage at ease but of the countries they visited.

Then as now, the Middle East was a combustible area. There were riots and slaughter in Syria and the world’s major powers — Russia, the Ottoman Empire, France, Austria and Britain — were jostling for control, particularly as the Suez Canal was under construction and about to open the trade routes to the East.

Then as now, royalty had its share of unwanted publicity. In September of the previous year when Bertie was stationed near Dublin, Ireland, with his battalion, his brother officers had smuggled a prostitute, one Nellie Clifden, into the barracks. Prince Albert and Queen Victoria were appalled at his behaviour and Bertie’s father had a long heart-to-heart with his errant son which took place on a walk during a heavy downpour. Albert died soon after of typhoid but Victoria laid some of the blame on her son.

Even though the court was in mourning, young Bertie’s tour had already been organised, so off he went with a group of chaperones, not least General Robert Bruce, the prince’s strict governor who was under orders to keep an eye on him. Bedford joined the group laden with his equipment, which included cameras, tripods, chemicals, plates, lenses and a portable darkroom.

In February 1862, the Photographic News wrote: “We have much Pleasure in announcing the first public act which illustrates that the heir to England’s throne takes as deep an interest in photography as his late royal father. In the Eastern tour which he is about to take in as private a manner as possible accompanied by a very limited suite eight gentlemen. Only Mr Francis Bedford, photographer, forms one of those eight.”

Bertie travelled to Calais, by train to Austria and on to Trieste on the Dalmatian coast. There the royal yacht “Osborne” took on supplies — one record lists delivery of 30 fowls, 24 pigeons, 36 quails, 200 eggs, 150 oranges and 24 bundles of asparagus — and the group sailed to Venice for two days before voyaging down the Dalmatian coast to Corfu.

On March 1 the royal group arrived in the Egyptian port of Alexandria and the youthful prince, free from mother’s watchful gaze, and, presumably with Bruce’s approval, rode through the streets of Alexandria on a donkey

He was to spend 28 days in Egypt, taking in Cairo’s bazaars, the Valley of Kings, Aswan and Thebes, along with that most popular of all tourist attractions, the Pyramids.

In his rather pedestrian journal he wrote, “We had a charming little encampment just below the Pyramids where we slept for the night.” And he deemed the ruins on the island of Philae “beautiful and most interesting and Mr Bedford the photographer who came from England with me and our party took some very good views”.

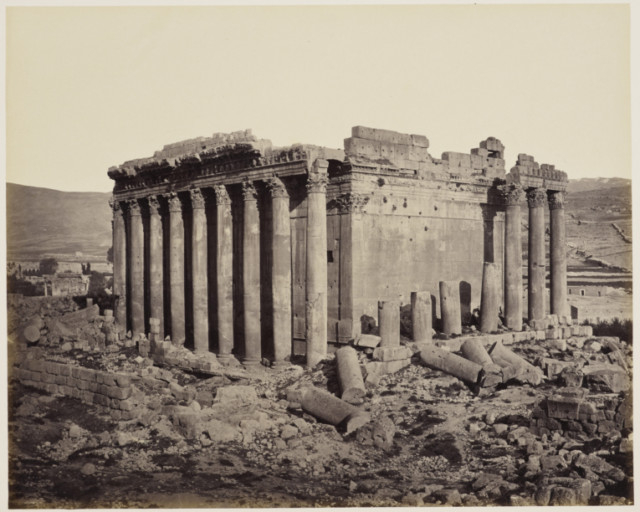

His “good views” provide a fascinating historical record of the crumbling streets of Cairo and the mosques, such as the Mehmet Ali, which tower over the surrounding city. Just a handful of guides and a solitary camel shelter in the shade near the Pyramids, and tucked into the massive colonnades of the Temple at Edfu, which had only recently been rescued from millennia of sand, is Bedford’s portable darkroom guarded by a huddle of locals.

The pictures are pinpoint clear, maybe due to the “old technology” of glass negatives, and Bedford enhanced the already spectacular sights by adroitly capturing the long shadows that fell across the ruins.

In one picture, Bedford persuaded the prince to pose rather awkwardly on a camel and photographed him and his travelling companions in front of the Pyramids on the beasts. One scene has the prince relaxing on the stones in Karnak, which is part of ancient Thebes, in the company of his uncle, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg, Prince Albert’s brother, and the Duchess — an incongruous gathering of European royalty in an ancient temple.

“We rode over first to see the temple of Rameses II,” he wrote. “It is the finest I think I have seen and it is very extensive. We remained there some time there and lunched.”

They moved on to Palestine, landing at Jaffa on March 29 and embarked on a tour on horseback of the Biblical sites, often living in tents with Turkish cavalrymen for protection.

Bedford captures the whitewashed houses of Bethlehem, with the donkeys in the square, the dusty, scrubby trees on the Mount of Olives and Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock in the background. As he was travelling with the Prince of Wales he was allowed permission to photograph in the “noble sanctuary”.

The incorrigible Bertie, meanwhile, had slipped away to be tattooed on his forearm with the five crosses that formed a Crusader’s Jerusalem cross. It is a picture that Bedford did not take.

As they headed north, the prince records, “We rested under a fig tree at 12 0’clock on the site where once the city of Capernaum is said to have stood. And Mr Bedford photographed us ‘en groupe’.”

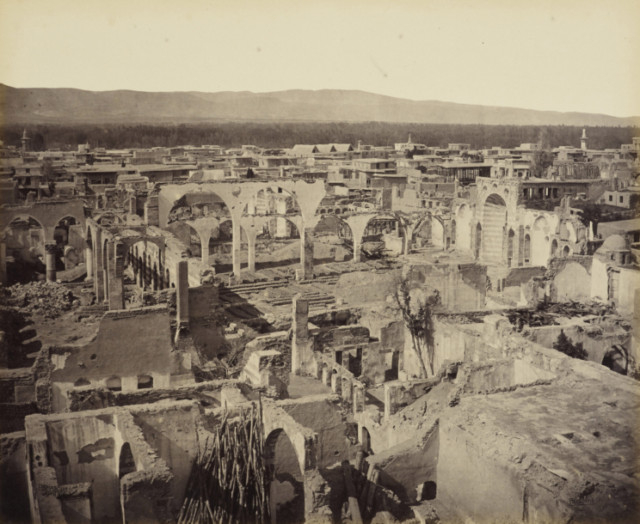

In Syria and Damascus they encountered scenes of destruction distressingly similar to today’s. In 1860, the conflict between Christian Maronites and the Druze had flared, with a non-Druze force, abetted by the Ottoman army, killing thousands of Christians in Damascus. Bedford’s pictures capture the terrible destruction with all the immediacy of today’s war journalists.

“After lunch we visited the Xtian (corr) quarter which is now all in ruins since the terrible massacres in 1860,” Bertie wrote. “We saw specifically the ruins of the Greek churches and the house of a rich Xtian which once were beautiful and are now a heap of ruins.”

They set off on the journey home, calling in at Rhodes, to Istanbul and on to Athens, where they posed under the columns of the Parthenon. General Bruce might have reflected that it was his father, Thomas Earl of Elgin, who had been responsible for the removal of the marbles that bear his name.

Eventually, on June 14, they reached Folkestone and the Prince ended his four-month expedition at Windsor Castle.

As for Bedford, the photographs were the apogee of his career. He was permitted to hold an exhibition on Bond Street, about which The Illustrated London News said, “Under adverse circumstances is very extraordinary and his results are in almost every instance highly successful”, and The Times commended, “We feel that there is a truly poetic rendering of the ruins of ages …”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

“Cairo to Constantinople: Early Photographs of the Middle East” runs at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, until July 21.