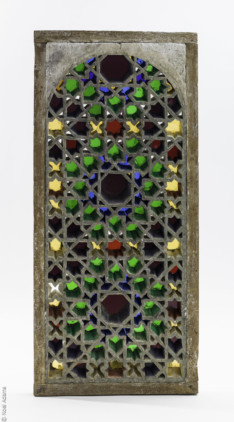

Put a square on another square, rotate it, and you get an eight-point star. Put that star with others, and you get new stars and new squares. Set those into a lattice of multicoloured glass, like the 15th-century north African window in this new exhibition, and you get an object of prismatic, mathematical beauty.

Overlay the fact that Christian Spain used this star motif in its own mudéjar style while at the same time abhorring the religious culture that made it — and you also get a paradox that Europe is still puzzling out.

In putting together “Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World”, Tunisian curator Sabiha Al Khemir has used light, geometry and other motifs to explore unifying themes in some 150 pieces from across the Islamic world, dating from the ninth century onwards.

Organised by the Seville-based energy group Abengoa, this display of pottery, carpets, astrolabes (an astronomical and navigation instrument) and even such esoterica as tools for cosmetic surgery has found a fitting home among the patios of Abengoa’s cultural foundation. In March it will move on to the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas.

The title, of course, provokes certain reactions. “Light in art and science from the Christian world” would not, you feel, have the same impact. Yet for all the perceived Western ambivalence towards Islam, the fact that Islamic societies once spearheaded the march of reason and enlightenment is hardly much of a revelation. Not, at least, to anyone who is likely to take an interest in this exhibition.

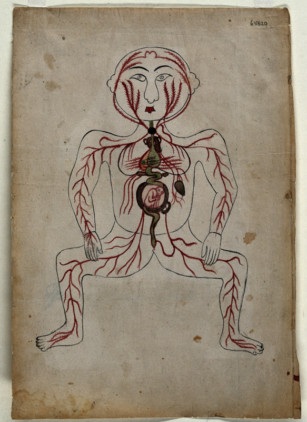

That said, the experience of seeing art and science objects in the same display works very well — far better, in fact, than a show dedicated to trumpeting the achievements of medieval Islamic science. The detail and choice of items manages to turn bridge-building platitudes into something much deeper. Just as beauty, geometry and philosophy seamlessly fuse in the window panels, it is interesting to pore over illuminated medical textbooks, and spot stylistic parallels with the lustreware (a technique of applying metallic glazes to pottery to create iridescence) and metal-inlaid art treasures of the first half of the exhibition.

Egyptian physician Ibn Ishaq’s 13th-century diagram of the eye, for example, is stylised and precise, its rich reds reminiscent of a tiny Indian ruby-encrusted glass cup from earlier in the display.

Throughout, exhilarating detail is squeezed into tiny spaces. The wafer-thin separation of the lines engraved on the brass astrolabe plates, for example. Or a copper inkwell, inlaid with silver from 13th-century western Persia. From its lid of floral arabesque, you move down past calligraphy, a frieze of animals, and then riders on horseback, all contained within a height of just 5.9 centimetres.

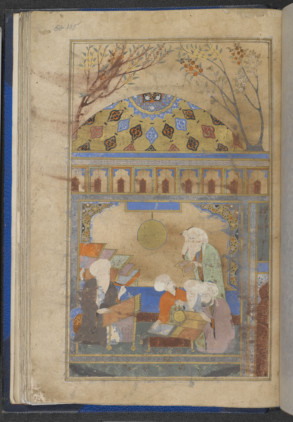

The composite nature of the medieval mind, its idea of reason, religion and beauty as different attributes of one whole, can be grasped in single objects here. At first sight, the openwork brass astrolabes look like sculptures by Arnaldo Pomodoro or Pablo Gargallo. One was designed by Ahmad Ibn Hussain Ibn Baso, an astronomer and “keeper of the times” at the Granada mosque in the 13th century; it is a lavish piece of art, created to take exact scientific measurements in the service of faith.

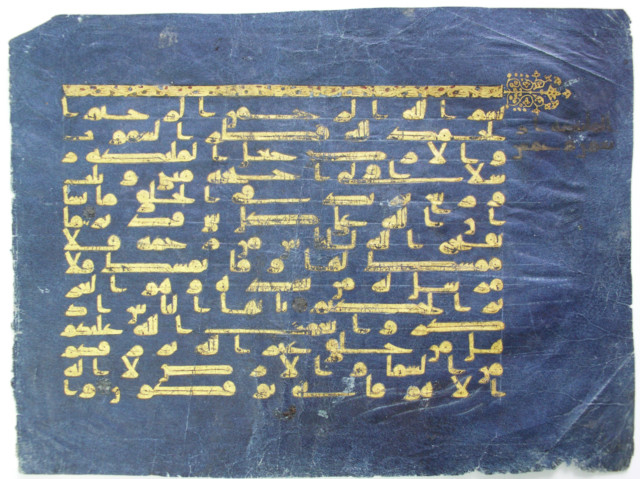

Al Khemir certainly has an eye for the all-encompassing metaphor. The tiny, inlaid inkwell from western Persia inspired her through the writing of the catalogue this summer, she says: a light-filled consolation for the darkness of the Syrian present. It is no surprise to discover that she is also a novelist. Her recent work of fiction, “The Blue Manuscript” (published by Verso), is an archaeological mystery depicting the famous Tunisian Blue Quran, whose pages have been dispersed across the world. Similarly, with her curator’s hat on, Al Khemir appears to be striving to bring objects scattered in time and space “back” to an essentialist unity.

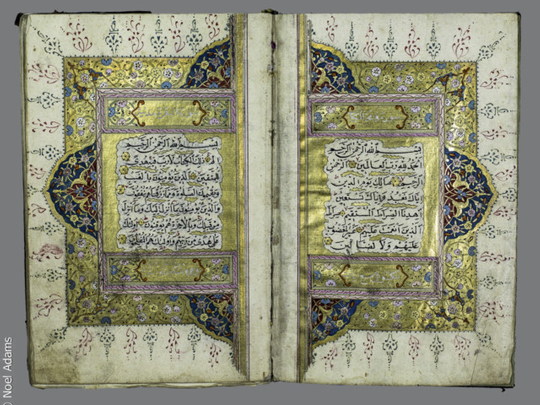

Two pages from the same Blue Quran of Al Khemir’s novel are also here, and to see the real object is certainly an experience. The resplendent, golden kufic writing on the indigo parchment is, as many have noted, like the night sky. In an exhibition that toured the United States last year, Al Khemir brought together a huge range of Islamic art under the particularly open-ended idea of “Beauty and Belief”. In the case of this exhibition, however, “light” does seem a tighter uniting force.

Elsewhere, thematic unity is achieved by a recurring radial design, most strikingly in a conical fritware (a technique that allows clay to be fired at lower temperatures) bowl from 13th-century Iran, with blue rays diverging from the centre. Stars too (and there must be hundreds here, on glass, ceramic, wool and plaster) radiate light, infinitely expansive, yet emanating from a single point. Even on Persian anatomical drawings from the 17th century, the transparent human body traces its net of nerves back to the head, seat of faith, reason and perception.

Sometimes there is the feeling that Al Khemir makes too generalised a claim for the virtues of Islamic culture. Some of the catalogue material, for example, makes a sweeping overview of the medical arrangements in the Islamic world, leaving you with a somewhat vague impression of justness and nobility. This, however, does not mar her object-by-object account, nor the experience of the display itself. Nor can it be overemphasised how beautiful most of those objects are.

Perhaps inevitably, many references to “bridge-building” surround the exhibition. This is likely to be a selling point, creating a narrative and attracting a public. But it risks attributing postmodern values to a world very different from ours.

After all, trade and interchange of technology is not the same as a benign attempt to “understand”. The rock-crystal chess pieces from Fatimid Egypt probably entered the treasury of Ourense Cathedral as booty — highly prized for their workmanship but seized on, you might imagine, with a vengeful whoop, rather than with a bridge-building murmur of appreciation.

Al Khemir agrees that it is unfair to impose a “mission” on objects that were conceived for other uses in other times. Viewers looking at the objects now do the bridging; their creators didn’t consciously “bridge”, she says, even in Muslim Spain where interaction between Jews, Christians and Muslims was complex and evolving.

And yet, at a scholarly level, interaction certainly went on in benign and creative ways, as she points out. Spain was the clearing house for rapid transmission of new knowledge into Europe, with many exciting new works of philosophy and medicine translated from Arabic into Castilian by a Jew, the Castilian then translated into Latin by a monk. Putting historical purism aside, it is hard not to find that enlightening.

–Financial Times

“Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World” is on at the Focus-Abengoa Foundation, Seville, Spain, until March 2014.