Biography review: Benjamin Britten

The tension between Benjamin Britten’s public and private lives holds the secret to understanding his creative psyche and his operatic characters

Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters of Benjamin Britten, Volume Six, 1966-1976

Edited by Philip Reed and Mervyn Cooke, Boydell Press, 880 pages, £45

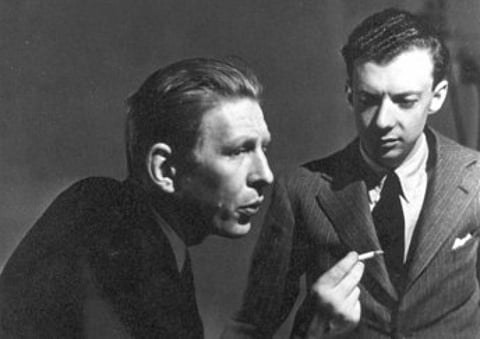

On June 8, 1953, when Benjamin Britten’s coronation opera Gloriana was premiered before an audience including the 27-year-old Queen Elizabeth and 600 royal courtiers, the production team consisted of a gay composer, a gay choreographer and a gay impresario. The work was based on a book by a gay writer and starred a gay tenor as Essex. A gay interior designer spent £1,660 (about £50,000 today [Dh278,063]) on temporary renovations of the royal box.

And yet paranoid homophobia was rife in British public life. When, late in 1952, Britten’s name was put forward as music director of Covent Garden, Britain’s leading opera house, rival composer William Walton snorted: “There are enough buggers in the place already, it’s time it is stopped.”

The following year the actor John Gielgud was arrested in a public lavatory and Britten was “interviewed” by the police. Even in private, homosexual acts between two men were a criminal offence. They would remain so for another 14 years. That tension, between private morality and public decorum, became the leitmotif of Britten’s adult life. Much of his creative inspiration was to be found in his sexuality and his — or society’s — conflicted response to it. The same tension lurks on almost every page of a flurry of books marking the composer’s centenary.

In our more open-minded age, it may seem surprising to discover how obsessed 21st-century Britten studies are with Britten’s sexual orientation, but it remains the key to understanding his creative psyche and his operatic characters: Grimes, the outsider-in-society who abuses child-apprentices (Peter Grimes); Vere, the naval captain who struggles to reconcile repression and gay desire (Billy Budd); Aschenbach, the vulnerable old artist who draws inspiration from beautiful unattainable boys (Death in Venice).

Britten’s oeuvre is intensely preoccupied with love and the futility of struggling against it, and most Britten admirers are at ease with this. But it never fails to astonish these same people how luridly Britten looms in the public domain whenever new revelations surface about his love life. The latest concerns the degenerative heart problem suffered by the composer in his final years, leading to his death in 1976 at the age of 63. Could it have been caused by previously undetected syphilis, contracted in his twenties after he began a lifelong partnership with the less-than-monogamous Peter Pears, as documented in Paul Kildea’s superb new biography Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century?

The evidence, while not conclusive, has a ring of truth. It puts Kildea, an Australian musician and administrator based in Berlin, firmly outside the “Aldeburgh stable” — a loyalist group, rooted in the Suffolk town where Britten and Pears founded a still-flourishing festival, which has striven to control and purify the composer’s image since his death. Its contribution to the centenary is twofold — Benjamin Britten: A Life for Music, by East Anglian author Neil Powell, and Letters from a Life, edited by Philip Reed and Mervyn Cooke, the final volume of the composer’s correspondence, covering his last decade.

While differing in style and approach, each book illustrates the degree to which this intensely private but demonstrably proper Englishman transformed British musical life in the postwar era. Besides advancing standards in public performance and setting new goals in music education, Britten created a large, performable body of works, the quality and international popularity of which no English composer before or since has emulated. We are only now, more than 36 years after his death, getting to grips with his astonishing achievement.

Of the two “Aldeburgh stable” volumes, Letters from a Life is by far the most engaging and informative. Led by Britten’s musicologist acolyte Donald Mitchell and his successors, the Britten-Pears Foundation has spent the past 20 years combing an extensive legacy of documents. The aim has been to trace Britten’s life and activities through his own words, free of the gossip and speculation that surrounded the composer in his lifetime and grew after his death.

This is patchwork biography. While opening a vast tranche of material to public dissection and expanding our knowledge of Britten’s daily business, the letters — always pleasant and practical — tell us little about his inner world. Two of the most influential figures in his development, the composer Frank Bridge and the poet W.H. Auden, are represented by a single letter apiece, and the estate has been unable to secure the rights to letters sent by the ageing, ailing Britten to Ronan Magill, his last adolescent crush.

And so Britten’s words are dwarfed by long, explanatory annotations, often focusing on tangential minutiae. These create a disjointed jigsaw of characters and events, and allow the compilers to throw veiled potshots at those outside the “Aldeburgh stable” — mainly the late Humphrey Carpenter, whose 1992 biography of Britten did so much to expose the unattractive aspects of his personality.

Unlike the early volumes of correspondence, which threw new light on Britten’s adolescence and early creative development, the last selection of Letters from a Life covers well-worn territory. Its staging-posts are Owen Wingrave, Death in Venice, Phaedra and the String Quartet No 3, as well as the conversion of the Snape Maltings into the Aldeburgh Festival’s main venue, its destruction by fire in 1969 and its speedy rebuilding.

Britten scholars will be fascinated by details of his abortive Anna Karenina project, for which he wanted a Bolshoi Opera premiere in Moscow, while noting his reluctance to join other United Kingdom-based artists in condemning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968: he feared such a move would jeopardise his ties with Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, whose wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, was to have sung the title role in the opera.

Others will savour his correspondence for the way it lifts the lid on the English musical village — polite on the surface, scheming beneath. Britten dissembles to people he is in the process of jettisoning from his life, such as Stephen Reiss, the first manager of the Maltings. He characterises the soprano Elizabeth Harwood as “a silly little thing ... with a sweet voice” and frets over the reluctance of sometime collaborators to drop everything the minute he needs them. Between the lines Britten behaves ruthlessly, subordinating everything to his compulsive creative urge — usually to his friends’ dismay and posterity’s benefit.

We also discover that, although he had written Owen Wingrave for television and was involved in the BBC’s filming of Peter Grimes in 1969, Britten didn’t own a television set until Decca, his recording company, gave him one for his 60th birthday, after his unsuccessful heart operation. Nevertheless, he was no ingénu: his work for the General Post Office’s film unit in the late 1930s had taught him how to use the medium to his advantage.

While Powell’s biography provides a reliable, uncluttered narrative, useful for Britten beginners, it adds no insights of its own. It comes across as a “life” without the “works”, because Powell lacks the musical background to do the latter justice. His opinions are mostly second-hand and generalised.

He writes like a dutiful courtier, discussing his master’s misdemeanours in a way that resembles a veiled defence. He fails to explore Britten’s pacifism or explain the background to the composer’s 1939-1942 American adventure.

There is little sense of Britten’s psychological complexity — or of cultural context, so important to an understanding of Britten’s challenge to English philistinism. This is where Kildea scores handsomely, and his book — a seamless interweaving of life and works, the one always illuminating the other — must now rank as the standard work of reference. He navigates with due care the rape allegation from Britten’s school days, describes him at 19 as “a young boy, just come out of the egg” and resists the temptation to “write up” his student pieces. After Bridge, who did so much to open the young composer’s eyes intellectually, culturally and technically, the biggest influence was Auden, who “bullied and cajoled his new friend ... to experience life as he did”.

It was thanks to the gay cosmopolitanism of the Auden circle that Britten progressed from the sublimated sexuality of public-school relationships to a state where, by mid-1936, “the problem was less realising the nature of his sexuality, more finding an appropriate outlet for it”. The cosy cosseting of his middle-class upbringing in Lowestoft fell away and by 1939, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he was in bed with Pears (an event the tenor was to recall in a touching exchange of letters with Britten in 1974).

Kildea makes crystal-clear that their “pact” thereafter was based on a “shared, instinctive response to music”, even when their needs and interests diverged. Pears enjoyed the seductive whirl of the city; Britten hated it, for it was the very bourgeois conventionality of life at Aldeburgh that drove his work.

From 1957, when they moved into the Red House there, they slept in separate bedrooms, Pears seeking elsewhere the “frisson his partner was unable to provide”. For much of the 1960s it was not Pears but Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya and the German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau who acted as Britten’s muses.

As for his final years, it is striking how little time they spent together. Pears “saw no reason to change the habits of a lifetime” and refused to admit his partner was seriously ill, attributing the painful slowness of Britten’s recovery to his notorious hypochondria. “Uncle Pears” (Stravinsky’s term) does not emerge from this book in a flattering light.

Nor does “Aunt Britten”. By turns priggish, prissy, petulant and puritanical, the “spoilt boy” only collaborated “with those who made him feel safe and did not challenge him socially or intellectually”: hence the need for everyone to tiptoe round the composer’s Aldeburgh court, creating a culture of secrecy and cliquishness.

Does this really matter? Artists are ultimately judged by their creative legacy, next to which personal quirks fade into insignificance. Britten’s misfortune, if one can call it that, was to inhabit an age in which a brilliant composer’s every letter and acquaintance could be documented, leaving a trail that would turn his private world into public property.

– Financial Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox