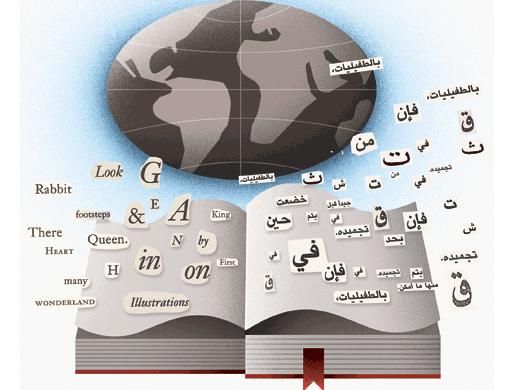

Until recently, the average Western reader would have known little about Arabic literature. He would perhaps have heard of the Quran but would have found it difficult to understand it.

The only other book of Arabic origin he would have come across — most likely, through expurgated renderings of its stories to entertain children — would have been A Thousand and One Nights, better known in the West as The Arabian Nights.

How then, is it that anthologies of world literature produced in America invariably contain examples of modern Arabic literature from the many translations done in the past few years?

The literary renaissance that commenced largely in Egypt in the middle of the last century was fortunate in having several writers of good stature. I refer to such writers as Taha Hussain, Yahya Hakki, Tewfik Al Hakim, Yousuf Idris and of course, Naguib Mahfouz. Even before I went to Cairo in 1945, I was interested in the new wave of writing and had already published several translations of stories by Mahmoud Teymour for small literary magazines in England.

Uphill task

A bit later, I translated a volume of stories by Mahmoud Teymour. It is no surprise that I was forced to publish it at my own expense, and finding a publisher has long been one of my main difficulties while trying to present modern Arabic writing to the English-reading public.

After leaving Cairo in 1949, I continued to work on collecting material for a volume of Arabic short stories which would represent the best of what was being written in the genre. During the years that followed, while I worked in various parts of the Arab world, I would frequently visit Egypt, and on each occasion my friend Yahya Hakki would enquire whether I had found a publisher for my volume of Arabic short stories. 'What? Not yet?' he would ask me year after year and we would both laugh. I think we both secretly suspected that my great plan would never see the light of day.

By sheer luck, I met someone who knew someone high up in the prestigious publishing house of Oxford University Press (OUP) and they must have recognised that the volume was of importance. In this way, the volume of Modern Arabic Short Stories came out — much to the delight and astonishment of my friend Yahya Hakki. Thus, in 1967, in one volume, the writings of such talents as Naguib Mahfouz, Yousuf Idris, Tayeb Salih, Zakaria Tamer, Fouad Tekerli, Jabra Ebrahim Jabra, Gassan Kanafani, Laila Baalabaki, Abdul Salam Al Ujeili, and, of course, Yahya Hakki, were presented to the English-language reader.

This should, of course, have been a breakthrough for modern Arabic literature. However, the book came out at an unfortunate time — the Arab-Israeli conflict — and most people's sympathies were not with the Arabs. While sales in England were not particularly good, not a single copy of the book was bought by any Arab government or institution.

It is, therefore, not surprising that OUP didn't publish any more translations of Arabic literature.

However, as they say in English, when one door closes, another opens. Through OUP I got to know a certain James Currey. He was working for the well-known publishers, Heinemanns, and was in charge of their series called African Writers. I suggested that he might include such authors as Tewfik Al Hakim, Naguib Mahfouz and Tayeb Salih, all of whom were African as well as being Arab — to which he agreed. However, I was soon faced with the problem of where to slot works by Palestinian and Iraqi writers. Soon, it was agreed to launch a new series under the title Arab Authors, which had all works from modern Arabic literature which had been translated into English.

While the series did moderately well and was well-received by well-known critics such as the novelist Kingsley Amis, its sales did not match those of the African Writers series. The reason for this was simple: the books published in the African Writers series were written originally in English and therefore had a potential readership in their own country, whereas books in the Arab Authors series had all been translated from the Arabic and a translation would attract only foreign buyers.

Ray of hope

One of the difficulties I encountered in trying to get support for the Arab Authors series was that the writers came mainly from countries such as Egypt, Palestine and Sudan, it was countries such as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States that were likely to have money to spare. It was thus a delightful surprise for me when Issa Al Kawwari, who was for many years minister of information for Qatar, showed interest in the series and promised to buy 100 copies of any book I translated, on behalf of his ministry.

This was in marked contrast to the attitude of the government bodies in Egypt. I remember well that my friend, the poet Salah Abdul Sabour, who was the head of an organisation, had ordered 200 copies for a book of stories by Yahya Taher Abdullah. It so happened that Abdul Sabour had died in the meantime and I therefore went to see his successor. This official immediately told me that Abdul Sabour had died and that he, as his successor, would not honour his order. I was so taken aback that I retorted to the effect that both he and I would also no doubt die but that he should honour his predecessor's signature. The unpleasant meeting ended with me getting back on my feet and leaving.

It should be recognised that it is largely through the efforts of the press division of the American University in Cairo that modern Arabic literature has attained its present degree of recognition in the West. It was they who had become the exclusive publishers of Naguib Mahfouz's works, and his being awarded the Nobel Prize helped greatly in bring universal recognition to Arabic literature.

While living in Beirut from 1970-1974, I remember being approached to join a team of translators engaged on rendering Naguib Mahfouz's writings into English. Though I had been the first person to translate his work — a short story back in 1946 — I refused to take part in the project put forward by the AUC because of the method being employed: four different translators engaged in translating a single book. An Arab translator would do a preliminary rendering, which would be followed by other translators with different degrees of experience adding their own alterations. I feel that since it took one writer to write a book, it should not require more than one translator to translate it.

Fortuitous move

A bit later, I recollect meeting Naguib Mahouz at one of the Cairo cafés he frequented. I had expressed my surprise at him signing over all the rights for translating his work to the AUC in exchange for nothing. I remember clearly Mahfouz's retort to me, delivered to me with one of his usual laughs: "And how many novels of mine have you translated?" I had to admit that at that stage I had not translated a single novel by him.

It so happened that Naguib Mahfouz's willingness to sign up with the AUC without having any immediate return for such a signature was the most astute move taken by the writer. When it came to the question of the Nobel Prize committee considering a prizewinner among Arab writers, the members were able to make such a decision only after reading work in a language known to them, mainly English and, to a lesser extent, French. Thanks to the efforts of the AUC Press, much of Naguib Mahfouz's writing had appeared in English.

For some time, a small London-based publisher, Quartet, published my translations. When this company went broke, no one seemed to be able fill the gap.

However, the sudden appointment of Mark Linz to the post of director of the publishing division of the American University in Cairo saved the day. He, along with me, requested Naguib Mahfouz for permission to set up a literary prize in his name. While the prize was a nominal sum of money, the main reward for the winner was having his novel translated into English and published by the AUC Press.

Today, the situation has improved, because the AUC Press is now able to provide the funds for translating other Arabic books.

I feel that I have had the pleasure of taking part in the story of how modern Arabic literature went from obscurity to being recognised as part of world literature.

Just months ago, I received a phone call from Dubai from my friend, Mohammad Al Murr, who informed me that he had put forward my name for a new prize that had been set up in the name of the late Shaikh Zayed. A couple of days later I received a call from Abu Dhabi saying that they were sending me return tickets and I duly received the prize of the Personality of the Year. For me, it was particularly pleasing to be awarded a prize that had been named after Shaikh Zayed, a remarkable man who had done so much for his country and for the Arab world in general and who had, several years back, done me a great service.

New beginnings

This had occurred when, during one of my visits to Abu Dhabi, I was representing a company engaged in business in the Middle East, I was sitting with my friend Dr Ezzeddin Ebrahim in a café on the sea front. Suddenly, Shaikh Zayed entered the café in the company of several guards. My friend took me up to Shaikh Zayed and explained that we were working on translating the Hadith (Prophetic Traditions) into English. Shaikh Zayed addressed me in Arabic and was, I think, surprised to find a foreigner speaking reasonable Arabic. The upshot of the meeting was that Shaikh Zayed arranged for me to be able to go to Abu Dhabi on a regular basis to be able to work with my friend on a subject he held dear.

The scene is now set for modern Arabic writing to flourish outside the Arab world: qualified translators are now available and more and more Arabic novels are finding publishers in the West — as has happened with Ala Al Aswani's novel, The Yacoubian Building. It is also significant that America's leading publisher, Random House, has recently published an anthology of modern Arabic literature, an indication of global interest. Nothing now remains but for Arabic literature to continue to produce writers of real talent.