Afghanistan behind the veil

An exhibition at Gulf Photo Plus captures the spirit and beauty of women in the war-ravaged country through poetic images

Lana Slezic first went to Afghanistan in 2004 on a six-week project to do a photo story on the Canadian troops there. But the Canadian photographer of Croatian origin was so captivated by the country, especially its women, that she stayed on for two years. During this time she travelled around the country, speaking to and photographing various women who opened their hearts to her. Slezic’s soul-stirring photographs and heart-rending stories, published in her book “Forsaken”, vividly describe the difficult circumstances these women live in and the oppression, exploitation and injustice they endure in a war-ravaged country and in a male-dominated society.

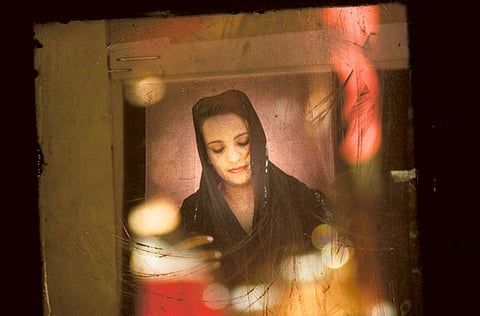

Slezic returned to Afghanistan in 2007 to create another photographic series titled “A Window Inside”. Her earlier work focused on the ugly world Afghan women live in, but this is a series of portraits that focuses on their inner strength and beauty. While the photographs in “Forsaken” are of women she had become very close with, these pictures are of women and girls she does not know. She met them at a roadside kiosk in a Kabul market, where they had come to have their pictures taken for ID cards, and Slezic requested them to pose for her.

Slezic has experimented with a unique technique in this series. She has shot the women’s reflections in the viewfinder of the Afghan photographer’s old box camera. Because of the texture of the ground glass, the subjects are highlighted by a soft halo of light that radiates outwards into the darkness of the surrounding camera box, lending the images a poetic, painting-like quality. And Slezic’s own scarves, reflected in the glass, add a splash of colour to the images, perhaps reflecting her desire to infuse some positivity and light into their dark world. In 2008 she won a World Press Photo Award for this series.

Slezic has travelled around the world exhibiting her photographs and sharing the stories of these women. She is now exhibiting the series in Dubai and introduced her work recently with an emotionally charged talk about her experiences in Afghanistan.

In an interview with “Weekend Review”, she spoke about her deep relationship with the Afghan women, her latest project on street children in India, and her desire to make a difference in people’s lives through her work. Excerpts:

What made you want to go back to Afghanistan?

During my earlier trip, I just could not leave, because I felt compelled to get to know the women behind the veils. But the two years I spent in Afghanistan were so emotionally draining — learning about these women and the terrible conditions they were forced to live in took such a toll on me that after coming back, I just could not bring myself to find anything else that I felt so strongly about. So going back to do ‘A Window Inside’ was in a way an effort to heal myself and accept Afghanistan for what it is. Also, when I spent time with these women in their homes, where they were free of their veils and social inhibitions, I found them to be warm, open and stunningly beautiful. I wanted to show this beauty and strength at the core of their being to the world.

Why did you use this unusual technique? Was it perhaps a way to deliberately detach yourself from your subjects this time?

I was fascinated by the old box cameras in Afghanistan and had discovered this technique by accident during my earlier stay; I always wanted to experiment more with it. The ground glass plate of the box camera is old, scratched and with chemical drippings on it, and this creates an interesting textured grainy image with a halo of light that disappears into the darkness of the box. I felt this was a unique, beautiful and unobtrusive way to capture these women. Because I was hidden behind the box camera, it was almost as if I was not there. Although I was not conscious of it, I think it was a way of looking deep inside my subjects while staying detached from them. But at the same time, the box camera is like a treasure chest filled with the stories of the Afghan women I befriended, and all my memories, experiences and emotions attached to them.

Did going back and doing this series help you heal?

It did help, but I know I can never really heal when it comes to Afghanistan. How strongly I feel about it can never change, and emotions will resurface every time I talk about it.

How did the whole experience change you?

I came close to these women, and laughed and cried with them, sharing their stories over endless cups of tea. I cannot ever be the girl I was before I went to Afghanistan, and can never go back to living in the bubble that was my life in Toronto. This experience has opened me up to accept humanity as it is. I know the world is not a nice place, and for so many people life is very difficult. I now know just how lucky I have been.

What difference do you hope to make with your work?

In this age of digital communication we are losing our sense of community. I always welcome opportunities to speak about my experiences, because people have to know and care about each other. I want to share these stories because they are important and need to be told. I hope it does make a difference by slowly permeating into people’s consciousness. With Afghanistan being in the news, most people will have some idea about the issues these women face. But I hope that when they look at these portraits, they will see these women as strong, resolute and beautiful people, and reflect on what their life may be like.

What do you think can be done to change things in Afghanistan?

The international community is helping in many ways. But the Afghan situation is very complicated and any real change can come only from the people themselves. Afghanistan has to change from within.

What project are you working on now?

I met my husband in Afghanistan, and we have been living in New Delhi, India, for the past four years. As a mother of two toddlers, I was drawn to do a photographic series on the street children in Delhi. I have grown very close to a group of such children, and am appalled at the terrible conditions they live in. The government does little for them and nobody else cares, or even notices them. I have taken pictures of them in the dilapidated shelter they call home, and on the streets. And this time I am experimenting with Instagram to create portraits of these children that seek to focus on the latent potential in them, that which cannot be realised because of their circumstances. Once again this is a very emotional and deeply disturbing experience, and I hope this series and accompanying book, “A Walk in the Park”, will help make some difference in their lives.

Jyoti Kalsi is an arts enthusiast based in Dubai.

A Window Inside will run at Gulf Photo Plus in Alserkal Avenue until October 25.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox