The kingdom’s abundance of oil, amounting to 21 per cent of the world’s proven reserves, has meant that over the years its financial fortunes, if not absolutely its economic performance, has been at the mercy of fluctuating oil prices. Admittedly, it’s a difficulty that most countries would be content enough to tolerate.

Oil exports have generated earnings of approximately $550 billion (Dh2,020 billion) during the five years 2003-07, representing about 90 per cent of annual exports, 75 per cent of the government’s budget and 40 per cent of nominal GDP. Clearly, those are formidable numbers.

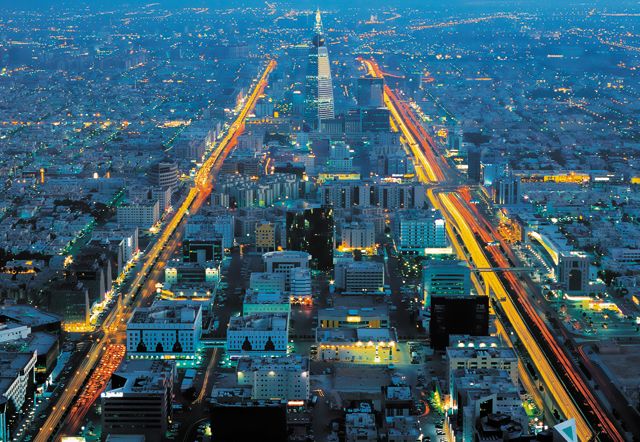

Reducing dependence on a single source has been at the heart of Saudi economic policy for many years. Of course, the diversification process is made easier for being funded by revenue from the oil sector. Just as the energy resource transformed the kingdom from a basic agricultural society into a global economic power with a modern infrastructure, it is now enabling the building of strong positions in a number of sectors (indeed as an industrial input itself) as well as helping to withstand the current economic crisis, through large accumulated foreign reserves.

Five-year development plans have had as their key plank the promotion of private activity, with the privatisation of sectors such as power and telecommunications — which as a consequence has attracted foreign investment — as well as accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and lately the plan for the so-called Economic Cities.

Running in parallel with the drive to broaden the economy has been the need to increase employment opportunities for an expanding and youthful population.

Foreign investment

In 2000 the Saudi Arabian General Investment Authority (Sagia) was created to encourage foreign direct investment (FDI). That year a new law gave foreign investors the right to the same benefits, incentives and guarantees as offered to Saudi individuals and companies. It also allowed them to own property and real estate. Membership of the WTO since December 2005 has given Saudi products greater access to global markets, besides its encouragement of foreign investment.

FDI amounted to $24.3 billion (Dh89.2 billion) in 2007, an increase of 33 per cent over the previous year, according to data from UNCTAD’s World Investment Report, continuing an impressive trend from near to nothing comparatively in 2000. International investors have been joining Saudi partners to set up ventures attracted by, among other things, a modern infrastructure and cheap energy supplies. As one example, the French energy company Total recently signed a joint-venture deal for an oil export refinery and related contracts at Jubail worth nearly $10 billion.

According to a 2009 report issued by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank, Saudi Arabia topped the Middle East and North African (Mena) countries in terms of an attractive investment environment.

The landmark Economic Cities project, specially designated economic zones, is supposed to be completed by 2020, dispersed across the country to promote the regions, and intended to contribute $150 billion to annual GDP.

Of course, the global credit crunch has intervened, with some knock-on regional effect, besides a domestic lending fright (see accompanying article). Yet, an improvement in banks’ risk appetite indicates that worst of the credit crisis seems to have passed.

While diversification and FDI will undoubtedly be checked in the current year, Saudi Arabia can nevertheless reap the benefit of having pursued a conservative financial policy during the boom years. The funds in reserve are likely to be tapped, with the government committed to stimulus spending, particularly on capital projects, in an effort to contain the current downturn.

In January this year the kingdom unveiled its largest-ever annual budget, with government spending boosted. While some of the more expansive planned projects, such as the aforementioned Cities, may presently be subject to financing constraints, the non-oil private sector will slowly expand its role, on the back of government contracts.

The fiscal deficit for 2009 is planned at SR65 billion (Dh63.6 billion), with forecast expenditure of SR475 billion (15.9 per cent higher on the year) and revenue of SR410 billion (8.9 per cent lower). It is noteworthy, however, that Saudi Arabia, like other Arab oil-producing countries, has traditionally presented conservative government budget estimates. An announced budget surplus of SR40 billion in 2008 preceded an actual outcome of SR590 billion.

As to the balance of payments, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Saudi Arabia’s current account will record a deficit in 2009-10, for the first time since 2002, as a narrowing trade surplus is insufficient to offset increased import expenditures.

Growth prospects

All eyes will remain on growth prospects, though. The rebound of oil prices to around $70 (with Saudi Arabia believing that $75 is a fair target for Opec to seek), and the government’s ability to maintain and indeed raise its spending, will ensure that Saudi Arabia will be among the earliest economies to pick up. EIU is forecasting a recovery in GDP growth to 3.3 per cent next year, from -1.0 per cent in 2009 (a figure reaffirmed by the IMF this month), rising towards 4 per cent by 2012.

Among other forecasters, Deutsche Bank’s team expects “more of a V-shaped recovery than in other GCC economies, with a greater political push to keep investment projects on track, as well as supportive monetary and fiscal policy. Investment-to-GDP has inched up during recent years, but remains the lowest in the GCC at 19.3 per cent at end-2008. This has, however, meant that Saudi does not face the same pullback in investment as is likely in other parts of the region, and we expect the economy to bounce back to pre-crisis growth rates more quickly than other countries in the region.”

Beneath that immediate prospect, basic creditworthiness counts for a lot in an age when financial fragility has been exhibited far and wide across the world. According to recent analysis produced by Standard Chartered Bank, “among the GCC countries, Saudi Arabia’s asset position is the most robust relative to its external debt, with an assets-to-debt ratio of 12 times,” the others some way behind (Kuwait at eight times).

But it is the potential outlook which seizes the imagination.

“Taking our current forecasts of $85 per barrel in 2011 and increasing the oil price by $5 per year over the next ten years, and conservatively assuming a constant production of 10 million barrels a day, produces revenues of four thousand billions US dollars over the period.” You might call that “mindboggling”, Deutsche Bank says.

Apparently, oil cannot be physically compressed. Much the same could be said of its ongoing support to the growth of the Gulf region, wherein Saudi Arabia, favoured by innate circumstances and applied control, clearly leads the way ahead.