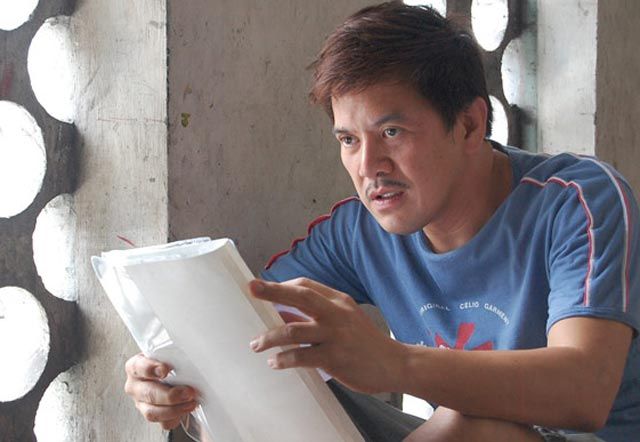

I wondered if I was calling the right guy when Taylor Swift’s Love Story came blaring down the line instead of a usual ringtone. Was this really the man who found fame for his indie films about dismembered bodies and massage parlours in the slums of his native Philippines? Was this Brillante ‘Dante’ Mendoza?

“Yes,” comes the stifled reply from a man still trying to find his bearings, having returned to a city ravaged by deadly floods. The winds of Typhoon Ondoy have barely had a week to subside in Manila, and Mendoza, who’s just arrived on a flight from Bangkok where he screened Lola (Grandmother), has had even less time to re-adjust to his newly upturned surroundings.

Aside for his taste in bubblegum pop, his voice just doesn’t sound like that of a man capable of “unremittingly tedious, harrowing or vile” cinema, as The Telegraph so aptly said of Kinatay (Butchered), the “horribly unforgettable denunciation of societal corruption,” which won him Best Director at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival.

A film about a young criminology graduate who accepts a mysterious job offer that involves the murder of a young woman and the scattering of her body parts, Kinatay was no let-up from Mendoza’s usually explicit, violent and overtly sexualised repertoire.

Shocking to the core

The film was blasted by Chicago Sun Times columnist Roger Ebert as the worst ever shown at Cannes, as much for its ill-lit and shaky techniques as its gruelling subject matter. But Mendoza, who strives for lifelike, documentary-style footage with on-the-spot acting, has become no stranger to the critic’s wrath.

His 2008 film Serbis (Service), which won a Golden Kinnaree at the Bangkok Film Festival, is about a family-run movie theatre that offers more than just popcorn in the back row. It sparked both jeers and walkouts when first shown. While Masahista (Masseur), his debut effort which follows love developing in a gent’s massage parlour, (a 2005 Golden Leopard Award winner at the Locarno Film Festival), was perhaps the most bitter pill to swallow for those who thought they knew this unassuming 49-year-old from sleepy San Fernando in Pampanga.

Mendoza says, with a tinge of sadness in his voice, “I think my family were shocked at first, I don’t think my brothers and sisters knew me as well as they thought. Maybe I shouldn’t have exposed certain aspects of my character so much, but it’s unavoidable. My film is my soul.”

Describing himself as coming from a normal, simple family in a traditional and typically conservative province in Central Luzon, Mendoza says there was nothing extraordinary about his upbringing.

“I was introvert, didn’t talk a lot and didn’t reveal my thoughts, but I was very observant of those around me. And these films are all partly based on true stories.”

As much as Mendoza respects the critics’ opinions, all negative reactions that have stemmed from the big screen realisation of his darkest thoughts were silenced into submission after one man jotted down his appreciation of Mendoza’s work in a personal letter.

“Quentin Tarantino said he completely understood what I was trying to do. To be up against a name like his at Cannes was recognition enough for me, but to win Best Director and have one of my idols express appreciation for my work was truly inspirational.”

Brillante Men...Who?

Appreciation has been harder to come by from within the Philippines, however. After much media pressure, President Gloria Arroyo was the last, and seemingly most prompted person, to congratulate Mendoza following his Cannes success. Secretly, Mendoza wants more government support for the island nation’s struggling independent film industry.

“But how can you expect this when you produce films that scathingly attack the Filipino system?” I retort.

Mendoza laughs, “I’m doing good for the country. Sure, you may say I’m not showing the rosier sides of life. But first and foremost I am a filmmaker, not a goodwill ambassador or a travel rep.”

“My films are truthful, I don’t strive to be controversial, just real. And underneath the darker, angrier elements of my films, I hope people see the positives. Hopefully the Filipino spirit to survive poverty and corruption shines through.”

The Film Development Council of the Philippines offers support to independent filmmakers, but needs to see a return on their investment. Like a loan with the bank, if the film doesn’t make a profit, you may be left owing the fund and even having to surrender the rights to the film.

Mendoza, who’s Dh780,000 to Dh1 million budget films are produced at a snip of the price Tarantino, Pedro Almodovar and Ang Lee play with, arrived in Cannes not by private jet or limousine, but by the second class carriage of a train from Paris with his film reels clutched to his chest. “When you’re from the Third World, you don’t think twice about getting to an awards ceremony by train,” he says of the comparison.

Only rich principles

Asked if he’d consider ‘dumbing down’ content to get government funding, or even selling out completely to produce more commercially viable box office novellas, Mendoza quips, “I’m uncomfortable with that. It’s not that I’m an activist or in it for the controversy, it’s just that I need to be honest with my feelings and articulate the type of stories I feel I need to voice.” “The impact of those films only lasts a short time, while you’re inside the movie theatre, I want the effect of my films to last much longer than that.”

But he agrees that the Filipino viewing culture has been so desensitised by celebrity and soaps that the country probably isn’t ready to accept alternative cinema.

“It’s not their fault, we’ve been exposed to this style of entertainment since the American and Spanish regimes. Alternative cinema has been around only four or five years so it will take time to sink in, but Cannes was a great start.”

Beware of the vultures

Inside the Philippines, one group of people who are now acknowledging him more is the country’s politicians. He developed strong contacts in politics while working as a production designer on

TV commercials before he rose up the ranks into film after graduating from the University of Santo Tomas with a BA in Advertising. Many senators rang to congratulate him on his Cannes success. But is that just because election time is looming? Just as Danny Boyle’s Oscar winner Slumdog Millionaire was thrown into campaign debate in time for the 2009 Indian elections, will we see Mendoza as some May 2010 poster boy, siding with the candidate promising the most change?

He laughs, “So long as my conscience is clear, I see no problem in my relations with politicians, because I’ll never allow myself to be corrupted.”

Just as he didn’t let his family know the other side of him, he’s similarly coy (to the press at least) about how he came to be a single father with a 13-year-old adopted daughter, Angelica Gabrielle Mendoza. He’s continually heralded fatherhood over and above Cannes as his single greatest achievement, but as I try to delve deeper into the circumstances which brought the two together, he’s understandably protective. “That’s another interview.”

His latest film, Lola, shows a different side of Mendoza and the Filipino way of life. It focuses on the portrayal of family connections, culture and companionship rather than the seedier aspects, which the Philippines would happily hide. For once, a film of his has received entirely positive reviews. But if you think that that’s a sign of Mendoza getting soft, bowing to pressure or chasing the faster buck, then perhaps you don’t know him as well as you thought either.