A siege whose aftershocks lasted more than 30 years

Memories of those tumultuous days are still fresh in the minds of those who had seen history unfold

This article is the outcome of the compilation of numerous interviews and writings of Iranians who were directly or indirectly involved in the events surrounding the November 1979 occupation of the American Embassy in Tehran. The accuracy of the accounts were verified by cross-checking them against each other.

It was October 1979. The surrounding spaces and streets around the American Embassy in Tehran were filled with people discussing what should be done in response to the United States allowing the Shah to visit for medical purposes. Very few amongst them believed that the purpose of the Shah’s visit to the US was to receive medical treatment. The move reminded them of the America-orchestrated coup in 1953, when the Shah had fled the country and the popular, democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq was toppled. The Shah entered the US on October 22 — eight months after the victory of the revolution on February 11, 1979.

Young Iranians whose convictions ranged from those sympathising with ultra-left Communist groups to radical Muslims gathered in front of the embassy’s main door daily and shouted profound slogans against the Shah and the US, seeking the Shah’s extradition. The number of protesters increased every day, reaching several thousand towards the end of October.

In July 1979, the Islamic Associations of 22 universities had held a gathering at Tehran Polytechnic University (currently Amir Kabir University) to create an organisation that would “protect the achievements” of the revolution.

The first elected Central Council of the new organisation, then called the Office for Strengthening of Unity between the Islamic Associations of the Universities and Theological Seminaries (later, simply called the Office for Strengthening of Unity or OSU), consisted of Mohsen Mirdamadi, Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, Habibollah Bitaraf, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Sayyed Zadeh. From the OSU’s inception, it was apparent that Mirdamadi, Asgharzadeh and Bitaraf were the key figures who dominated decision-making within the Central Council. Key to connecting the OSU with Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic Revolution’s leader, was a radical cleric called Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha.

The person who first brought up the idea of seizing the American Embassy was Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, while Bitaraf and Mirdamadi also supported him. This was in August. They argued that the move was necessary to neutralise two groups of rivals. First, the liberals, that their presence in the government could divert the revolution, they reasoned. And second, the leftists, whose far-reaching anti-American propaganda could sideline the Islamic currents in the revolutions’ struggle against imperialism. During August and September, Ahmadinejad argued that the Communists were the main enemies of the Islamic Revolution and that the USSR Embassy should be seized.

The straw that broke the camel’s back

The admittance of the Shah into the US was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The radical Muslim students thought that “the countdown for another coup d’état had begun”. One week before the seizure of the US Embassy, the aforementioned three met with Mousavi Khoeiniha at his office in the Iranian national TV headquarters, where he supervised the TV programmes as Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini’s representative.

The purpose of the meeting was to ask Khoeiniha to seek Khomeini’s opinion regarding the plan. Khoeiniha welcomed the plan, but rejected the students’ strategy. Khoeiniha asserted that Khomeini faced political constraints that prevented him from approving the seizure. Khoeiniha suggested that the group should go forth with the plan and seek Khomeini’s reaction. If he supported the group’s actions, they would remain. If he objected, they would vacate the compound. In any case, Khoeiniha argued, at least the students would have protested American policies, thereby attracting the world’s attention to their cause.

The group formed reconnaissance units shortly after that meeting. One unit entered the compound as visa applicants. They were tasked with preparing a sketch of the compound including the buildings inside. Another unit assembled on nearby rooftops overlooking the embassy. They assessed the number of embassy security personnel including the US Marines and Iranian police guarding the embassy, drafting diagrams of building locations from above and the locations where cars were parked. Another unit located all of the entrances throughout the compound.

Two more events accelerated seizure of the US Embassy. News broke on November 1 about a meeting between Iran’s prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, and his foreign minister, Ebrahim Yazdi, who was also a pharmacology graduate from Baylor College of Medicine, with US president Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski in Algiers. Bazargan and Yazdi were both considered as pro-western, liberal figures. All of them were attending the 25th anniversary of the Algerian revolution. News of this meeting provoked a huge sense of resentment among all revolutionary factions, including radical Muslim students. The next day, Khomeini, in a fiery statement to the clergy and students, urged them to “expand with all their might their criticism against the United States”.

Time for action

The statements left no doubt among leaders of the OSU that it was time for action. The Central Council of the OSU decided to select 400 trusted students from four major universities. To choose the students, a small committee appointed by the Central Council of the OSU in each of the four universities would interview the trusted students. They would ask them only two questions: “Can you stay out of your home or the university dormitory for 48 hours?,” and, “Will you participate in a protest move against the United States?”

Those who said “yes” to both questions were asked to attend a briefing meeting. In the meeting, they were informed of the plan to seize the American Embassy. The embassy’s occupation would last between 48 and 72 hours, they were told. The seizure’s aim, the students were told, was to attract international attention to the issue of a perceived US conspiracy against the Iranian Revolution.

On November 4, 1979, a massive demonstration was organised. In order to be distinguished from other demonstrators, the students who were supposed to participate in the seizure of the embassy carried a picture of Khomeini with an armband on which it was written: “Muslim Students Following the Imam’s Line.”

They gathered at an intersection one kilometre east of the Embassy. At 10.30am, the group walked towards the embassy. Only 50 were meant to enter the embassy. The rest would remain outside to prevent people from joining their activities, which would create unintended chaos on the inside.

The students continued, passing the main entrance of the embassy. After walking 50 metres beyond the main door, embassy guards were caught by surprise as protesters suddenly returned to attack the embassy’s gate. A few female students were hiding metal cutters under their long veils (chadors). The gate’s chains were quickly cut and it was opened as others climbed over the walls. Immediately after the main group entered the embassy, the gate was secured again with locks and chains prepared in advance.

Trove of secret documents

The students broke into the main building where they faced Marines who guarded the embassy and were ready to shoot at them. A male and a female student shouted in English, “We are not here to hurt you! We just want to sit-in!” The marines, afraid of the seemingly angry students, shot tear gas. But because they were inside the building, the tear gas penetrated upstairs and throughout the building, making the situation intolerable for staff and the marines themselves.

A small group entered a corridor, at the end of which there was a steel wall. They heard a low noise behind the wall and suspected that there was something happening behind it. They concluded that it might be a door rather than a wall. They forced one of the hostages to open the door, as it was coded.

When the door opened, their jaws dropped. Before them, the students saw tonnes of secret documents in the form of papers, microfilms and microfiches. The noise had been that of shredders and incinerators. The students shut down the machines and guided the operators of those machines outside the room. Later, they painstakingly reconstructed those documents that had already been shredded. By 1.30pm, the radical students controlled the entire compound.

The streets surrounding the embassy were filled with thousands of angry people chanting slogans against the US with their clenched fists, demanding the Shah’s extradition. Thousands remained on the streets that night and several nights thereafter. The atmosphere was hysterical.

Ayatollah’s reaction

Yazdi, who had just returned from Algeria, rushed to the holy city of Qom where Khomeini resided. According to Yazdi, Khomeini’s first question was: “Who are these people?” Yazdi told him that they were students who introduced themselves as Khomeini’s followers. After Yazdi explained the situation and the way the incident could become problematic internationally, Khomeini said firmly, “Kick them out”.

While Yazdi drove back, Khoeiniha called Sayyed Ahmad Khomeini, Ayatollah’s son and confidante. Khoeiniha assured Sayyed Ahmad that all of the students were devout Muslims who truly were Khomeini’s followers. He added that following Khomeini’s statement to intensify resistance against America’s decision to allow the Shah into US, the students decided to occupy the embassy seeking the Shah’s extradition. To assess the real situation on the ground, Sayyed Ahmad flew to Tehran by helicopter.

When the crowd saw Sayyed Ahmad, they lifted him while chanting slogans in support of Khomeini and against the US. The frenzy on the streets shocked Sayyed Ahmad. In his return to Qom that same night, he reported to Khomeini about the hysteria on Tehran’s streets. He also reported on the massive secret documents seized by the students and the machines that had been working to destroy the documents as the students encroached upon the embassy.

The next day, on November 5, Khomeini called the US “The Great Satan” and the embassy “a den of espionage”. He said in a speech: “That centre that our youth went to, as we were informed, has been a centre for espionage and conspiracy.”

Taken hostage by hostage crisis

Tehran no longer controlled the course of events thereafter. On a daily basis, the students would reveal documents on the national television with regard to the perceived American espionage. In a twist of irony, the whole country was taken hostage by the hostage crisis.

A few days later, the moderate cabinet of Bazargan resigned, thus beginning the tumultuous years in Iran-US relations. Nobody could have imagined that aftershocks from that earthquake would last for longer than 30 years.

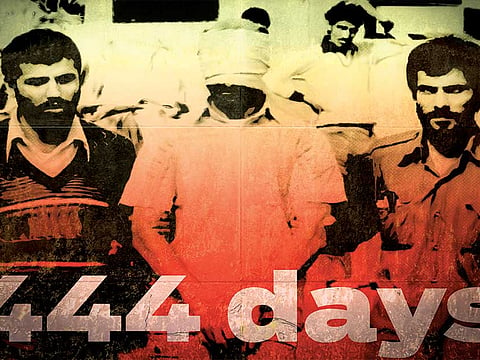

The hostage crisis that ensued and lasted for 444 days stood for something much larger than, and independent from a student uprising. Many argue that the conservatives took advantage of the crisis to neutralise their rivals, particularly the liberal current during that period.

Shahir ShahidSaless is a political analyst and freelance journalist writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace, published in May 2014. He lives in Canada.