A medieval breeze laced with the scents of flowers and spices will accompany you on your way through the narrow mazes and twisting alleyways of Khan Al Khalili bazaar, a 14th-century oriental market, but what will charm you the most is the scene of shops filled with papyrus of all sizes and colours.

In this market at the heart of the Fatimid Cairo, a Turkish caravanserai during the Ottoman era, much of the ancient heritage of Egypt has been carefully revived, including the craft of making papyrus.

In different shops around the place, there wasn't a single passer-by who wasn't interested in checking the attractive paintings and wall-hanging sheets of this forerunner of paper.

"Most papyrus art sold today comes from small workshops and factories based in the eastern governorate of Al Sharkia, 83 kilometres from Cairo. That was the source of papyrus even at the times of the pharaohs," Tarek Samy, the owner of a small papyrus stall, told Weekend Review. "With today's mass production, buyers should be wary of fake papyrus. Genuine papyrus, made from the ‘Cyperus plant', has its fibres in cross hatches [it is visible when you hold it up to the light]. Fake papyrus is made from banana leaf or sugar cane and is extremely brittle and deteriorates rapidly."

Samy explained that papyrus has a big market, accounting for about 20 per cent of souvenir sales in Egypt. Most tourists and even locals buy papyrus as gifts. Those with Judgment Day, Egyptian lunar calendar, Queen Nefertiti and King Tut are among the most sold."

The paintings, he said, are most often imitation prints of original papyrus art, with different colouring techniques such as gouache, graphite and aquarelle colours. These products can cost as little as $3 (Dh11) and up to $200 or more, depending on the quality of painting.

"I bought a small papyrus featuring the famous blue scarabs which bring luck, just as they were in ancient Egypt, but I have to admit there is a big collection to choose from and I noticed they were not only selling Pharaonic paintings on papyrus, there were other drawings of different Islamic eras, Chinese horoscopes and Quran verses as well," said Claude Monet, a French tourist.

Most vendors, said Haj Mahmoud Bahrawy, who has been working for more than 30 years in this craft, would start by giving you a demonstration to whet your curiosity on how modern papyrus is produced.

"Today's procedures are similar to what Egyptians used to do more than 3,000 years ago. The manufacturing process starts with stripping off the papyrus plant's green outer layer, then cutting the pith into thin strips, laying the strips in an interlaced grid pattern and pressing hard using a warmed press before soaking them in water for six days to get rid of the white colour. They are then soaked for ten more days to lend them a more brownish colour," Bahrawy said.

However, Bahrawy rued the fact that the end product tarnished the real art.

"Papyrus art of high quality must be handmade paintings by individual artists. That is much more expensive but that is how it was made in ancient times. Most of what is sold now are prints done by a machine," he said.

He displayed a rare collection of some of the works made by Dr Mahfouz Darwish, the former manager of Cairo's grand museum, who has now stopped drawing on papyrus. This makes the collection priceless, Bahrawy said.

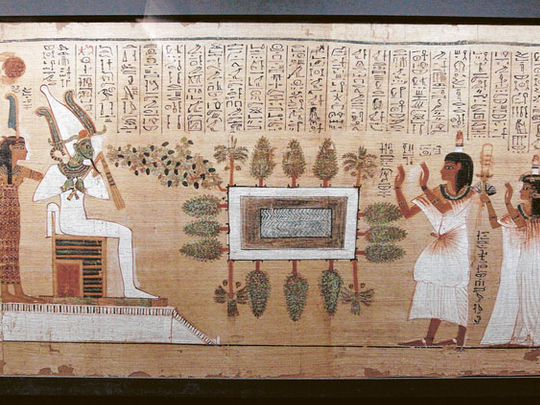

The lifestyle of ancient Egyptians has been best brought to life by papyrus art. The civilisation succeeded in living on for posterity, thanks to rolls and rolls of skilfully written papyrus.

Thousands of years after the civilisation ended, humanity came to understand their daily lives, walk in their shoes, meet their families, taste their food, enter their sacred world and get a clear glimpse of their hopes and fears.

Papyrus was principal to the ancient Egyptians. Dr Hussain Rabe'ei, professor of archaeology at Cairo University, told Weekend Review that much of what we know today about the life of the pharaohs is through papyrus writings.

"Ancient Egyptians have left so many artefacts, tombs and temples that describe details of their daily lives. But the words they wrote offered the best details. The ancient Egyptians were passionate about writing down everything — from magic spells, medical procedures to mythology and deities," Dr Rabe'ei said.

However, without the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and eventual decipherment of hieroglyphics by Jean-Francois Champollion in 1822, much of the written world of Egyptians would be lost in the fog of time, as scholars would have had to rely almost entirely on the accounts left by Greek and Roman authors, or the Bible, in which Egypt is mentioned.

The Rosetta Stone, which marked a turning point in the modern understanding of Egyptian hieroglyphics, was discovered by a French soldier coming with Napoleon's 1798 expeditionary army. It was a decree written in three scripts — one was Greek and the other two forms of the Egyptian language.

Many historians believe that the English word "paper" is derived from the Greek word "papyrus", which was first used by the Greek writer Theophrastus in the 4th century BC to describe this type of paper. However, in the Egyptian language, there is no hieroglyphic synonym for this word. It was referred to as "that which belongs to the house", as papyrus production was considered a crown-owned monopoly and the method of its production was a closely guarded secret.

The first use of papyrus paper is thought to be as early as 4,000BC, with the start of the 1st Dynasty, about the same time that ancient Egyptians developed a written language, on a medium other than stone, to transcribe upon.

Mohammad Fahmi, professor of ancient history, said that many people wrongly assume that papyrus was commonly used in ancient Egypt. In truth, however, papyrus was used for religious or literary texts only. And it was expensive, with one sheet probably costing the equivalent of $20 today.

In ancient times, for thousands of years, papyrus was the only writing paper in the region. So it became an economic factor for Egypt through export, which resulted in many efforts to find a local substitute throughout various parts of the Mediterranean. Attempts included using clay, wax tables, sheets and parchments as writing material.

However, they proved to be inferior in one respect or another to papyrus, which remained the primary writing material in the ancient world. Greeks and Romans relied heavily on papyrus for transcription; much information about the Greek civilisation has come to us in the form of writings on papyri. In the Ptolemaic period, when Greek pharaohs sat on the throne of Egypt, the region supplied the whole Roman empire with high-quality papyrus. It was used mainly by the literati, for legal papers and affairs of the state.

"As papyrus was light-weight, strong and durable, its production survived for more than 2,000 years. However, in the 10th century, Arabs introduced rags to make paper, which they had learnt from their Chinese prisoners. Though the new paper was less durable, the process was easier and less expensive. So Egyptians abandoned its production and neglected its cultivation. Some centuries later, papyrus paper had completely disappeared from the Egyptian scene," Fahmi said.

In ancient Egypt, the Cyperus papyrus plant, which grew abundantly along the banks of the Nile, was also used as the raw material for making baskets, furniture and medicine. The plant's root and stem were also used as vegetables.

For more than a thousand years, there was no more papyrus in Egypt and the knowledge of producing papyrus remained a secret until 1960, when Dr Hassan Ragab, an Egyptian engineer, showed up to rediscover this lost art.

The man who brought papyrus back to Egypt faced two main obstacles during his journey to becoming the founder of this new, thriving business in modern Egypt. The first was not having any papyrus plants left in Egypt; the second was rediscovering the production process — as the Egyptians never mentioned anything about how to make papyrus paper.

Strange as it may seem, Dr Ragab had to obtain roots of the Cyperus papyrus from Sudan. He then rented part of Jacob Island in the southern part of Cairo to grow papyrus and establish his Papyrus Institute, in 1968, in an attempt to show the public how it was done. Today, it has been turned into a museum that contains the largest collection of papyrus reproductions of all the famous paintings of ancient Egypt.

Due to its worthiness, papyrus paper has been found preserved in tombs and certain royal safes.

Ancient Egyptians allowed only experienced scribes to write on papyrus, as students at schools did not have papyrus to write on. Students used clay pieces called potsherds and broken pieces of pottery. Only when they were mature and old enough were they were given the permission to use papyrus. The occupation of a scribe was considered very respectable in society. The task of recording history, expressing everyday and extraordinary happenings was the responsibility of the scribe in ancient Egypt.

Though some scribes may have written letters or drawn up contracts for fellow villagers, others had more demanding jobs.

They may have had the responsibility of recording the harvest and collecting the state's share of it in taxes, calculating the amount of food needed to feed the tomb builders, keeping accounts on estates and order supplies for the temples and the Egyptian army. This was how they kept the government working.

Among the famous papyri that were discovered is the "Rhind Papyrus", an ancient scroll purchased in 1858 by Scottish antiquary Henry Rhind. It contains mathematical tables and problems. It is sometimes referred to as the Ahmes papyrus, after the scribe who copied it in about 1650BC. Another is the "Turin Papyrus", which was a manuscript of the 19th Dynasty (1190BC), a chronology of the Egyptian kings. It was commissioned by Ramses II and is presumed to end with his rule.

However, the most famous one is the "Ebers Papyrus", which is the oldest medical text and dates back to 1550BC. It reveals that the ancient Egyptians were aware of the existence of blood vessels and the fact that heart supplies blood to the body.

The more we know about the rich life that existed in ancient Egypt, the more we are curious to know more about this fascinating era. However, the search for more of these ancient secrets continues, as we try to piece together the puzzle.

Raghda El Halawany is a journalist based in Cairo.