Frankly, I thought a smart court would look smarter.

I had arrived at the National Tennis Center in Melbourne Park in my tennis togs for a computer-monitored hitting session at the indoor practice courts during last month’s Australian Open.

My court was the last one in a row, and it looked at first glance like all the standard courts that preceded it. There were lines, a net and a blue acrylic surface like thosein use at the Open.

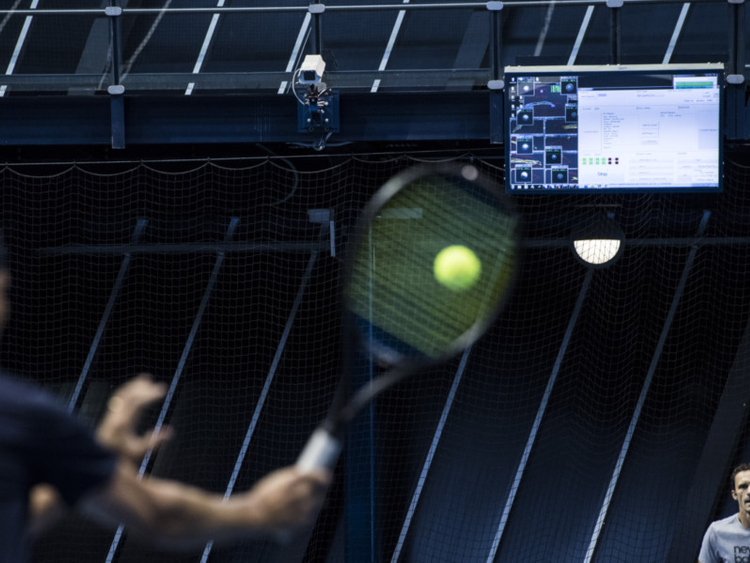

Then my guide, Machar Reid of Tennis Australia, began pointing toward the rafters, to cameras, 11 of them, and a large flat-screen monitor fixed high above the court. Eight of the cameras were Hawk-Eye cameras, ball-tracking devices sophisticated enough to be used to check line calls in major tournaments.

Smart courts are proliferating, giving players quick data and video feedback on their strokes and movement. The goals are to improve coaching and draw a wired generation to the sport. The company PlaySight recently installed 32 such courts at the vast new US Tennis Association national campus at Lake Nona in Orlando, Florida.

But the court used in Melbourne by Reid and his team has a different purpose. It is designed to measure minute differences in racket and string performance to give elite players a more reliable method of comparing equipment.

“In terms of players making multimillion-dollar career decisions and following their current process for equipment selection, I think it just beggars belief,” said Reid, who has the title of innovation catalyst at Tennis Australia and a license to dream big.

Racket manufacturers have begun using technology to help athletes choose their equipment, but Reid said most players still chose rackets based on “feel” rather than hard evidence. He says he believes that players can be fooled that way and that the sport is long overdue for a more analytical approach.

Players under contract with a racket company have limited choices, but even when they are free of commercial concerns, the process is typically unscientific.

“A lot of times, switches are made when you just pick up a friend’s racket and try it out for fun,” said Ryan Harrison, a US player ranked 62nd in the world.

Reid and Tennis Australia, the country’s governing body for the sport, want to make the process much less serendipitous. To demonstrate their method, Reid invited me — a 52-year-old former Division III player at Williams College who is no threat to the pros — to be a guinea pig.

I still play regularly, and the night before our session I had to establish my goals: more precision and bite on my sliced one-handed backhand; more power on my forehand and serve.

According to Reid, there are about “200,000 different potential combinations by the time you take into account all the different characteristics of a racket and all the different types of characteristics of string.”

But with my goals in mind, Reid’s team — which has a working agreement with the manufacturers Babolat, Head, Wilson and Yonex — chose just three racket models. I got two variations on each of them, so six set-ups in all with different string combinations but the same string tensions.

My rackets were in disguise, a standard procedure for Reid’s team: The paint on the frames was blacked out to hide the logos.

“The idea being that you enter here with no bias,” Reid said.

The drawback being that anyone who plays the game seriously can recognise, for example, the distinctive shape of a Babolat frame whether it is blacked out or not.

“But you won’t necessarily know the racket model,” Reid said. “Nor will you know the string set-up.”

Fair enough. And so, with the cameras rolling, I hit a series of forehand drives and then a series of backhand slices while Lyndon Krause and Olivia Cant — Ph.D. students in sports science at Victoria University in Melbourne — recorded and crunched the numbers courtside on a laptop.

I rallied with Reid, who by the way is quite a rallier. We did the forehands first: a minimum of 10 with both of us at the baseline, then another series with him feeding me balls from a position closer to the net. Why the two options? Because it is easier for a player — or at least this player — to replicate a stroke off a fed ball.

Keeping up with Reid was only my second-biggest challenge. The toughest was keeping the often subtle differences among the six rackets clear in my head.

“We don’t usually go with six different rackets with the pros,” Reid said. “Their needs are usually very specific.”

I took notes, which ranged from the complimentary (“Model No. 2: amazing power in extension with just a flick”) to the crotchety (“Model No. 5: far too much ping on contact, feels like a trampoline”).

By the end, it all got a bit blurry, but I managed to rank my racket preferences for each stroke and have occasional discussions with Reid as we checked the big overhead screen for data on net clearance, landing locations and speed.

I then finished off with first serves down the T, starting off strong and then losing my mojo.

Reid, who did his doctoral thesis on the serve, eventually made a suggestion.

“Like all of us as we age, the toss tends to drift out to the right,” he said.

I took note, put the toss straight over my head and — shazam! — my serve went down the T with power.

“You realise you have affected the integrity of the experiment?” I said.

“I couldn’t help myself,” he said.

The next day, Reid and his team presented me with a 10-page “performance report” with lots of charts, mapping things like my accuracy and power. The report said the best all-around set-up for me among the six options would be a Yonex Ezone DR 100 Blue with a polyester-gut string combination. It was similar, as it turned out, to the Head racket I use in terms of specifications.

If I wanted to take my spin and ball speed to the next level, the results showed, a heavier racket than usual for me, the Babolat AeroPro Drive with all-polyester strings, would be worth further testing — but only if I strengthened my upper body to lower the risk of injury.

This sort of clarity was appealing, and preventing injuries, particularly of upper limbs, is one of the main long-term goals of Tennis Australia’s program. With shoulder and wrist injuries now too common, the sport could use all the help it can get.

“The technology is not quite there, but it will be in place, I suspect, in a few years,” said Reid, who also thinks Hawk-Eye data from tournaments will allow players to better understand the injury risks.

“More widespread release of that data will be key,” he said. “Just by knowing how many shots players are hitting and at what speed and so forth, you can, through sophisticated math, then provide them insight into how much load they’ve incurred over three to four weeks compared to their historical data and tell them when to watch out.”

For now, too much of that data remains proprietary, and Reid’s smart court and adjoining workshop — filled with blacked-out frames and high-end measuring equipment — are best used by pros looking for fine-tuning. Reid said the two leading Australian women, Samantha Stosur and Daria Gavrilova, had used the system to test new string combinations.

But if the system can eventually do all that Reid plans, many far better players than your tennis correspondent are likely to follow, even if data, however precise, has its limits.

“I think most guys are willing to try it out if there is the opportunity to improve,” Harrison said. “But if the racket doesn’t feel good in your hand, then you don’t force it.”