A high-profile gathering in the past week in London, to debate a route to peace in Afghanistan, was quickly followed by a cause for disappointment.

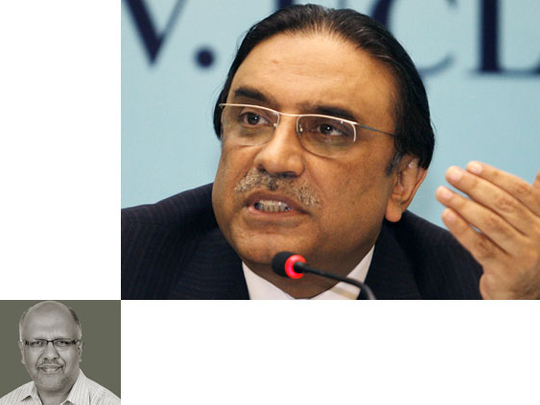

While Pakistan’s President Asif Ali Zardari, Afghan President Hamid Karzai and their British host, Prime Minister David Cameron, resolved to redouble their activities for peace in Afghanistan, following a meeting at Chequers, the British prime minister’s country residence, the Taliban immediately played down the meeting as a non-event.

For now, confusion surrounds prospects for a half sensible end-game in Afghanistan. Indeed, the key problem is driven mainly by the two main foes in the conflict — the Taliban and the US, to sit down and discuss a settlement.

Towards this end in the same week, news from Washington was hardly encouraging. John Brennan, President Barack Obama’s nominee to head the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), yet again publicly defended the US use of pilot-less drones for attacks in the border regions of Pakistan.

The policy, which has become controversial, given the number of innocent casualties over the years, comes as a stark reminder of the gap between the US and other players in the region.

For Pakistan, the use of drones not only violates the country’s sovereignty, which has only weakened under Zardari’s watch — given the slide in political, economic and security conditions that has taken place since he came to office.

More vitally, the continued US use of drones will likely keep Pakistan in a corner and simply make it unable to vigorously push a reconciliation plan while the attacks carry on.

Similarly, Karzai’s ability to speak for Afghanistan, as the US heads towards a draw-down of troops by December 2014, is quite unclear. He continues to preside over a state which must qualify among the world’s most dysfunctional ones. Following more than three decades of conflict, beginning with the 1979 military intervention by the former Soviet Union, the scars of war on Afghanistan’s body and soul are clearly visible.

In the past decade, since the US led the war following the 9/11 terror attacks on America, the bulk of the military effort has gone in to fuel the military conflict rather than tackling some of its root causes. Ahead of an expected US departure from Afghanistan, there is little evidence of much by way of signs of a vigorous rejuvenation of the Afghan economy.

Consequently, for at least a generation of young Afghan men, settling disputes and pressing for their rights remain possible only through the barrel of a gun. Going forward, there is hardly much that the US-led western coalition is either willing or able to do for changing what indeed appears to be a bleak outlook for the Afghan economy.

Yet, what indeed is a credible peace process is involving the key players. Without an active US participation across the negotiating table from the Taliban, there is little likely movement that will take place to even begin changing the powerful reality of conflict-ridden Afghanistan.

The absence of the US and the Taliban from the meeting at Chequers exposed a big gap in dealing with a far more complex conflict than what the world has seen for long.

The Taliban, with its ability to face up to the world’s best-equipped and technologically most sophisticated military coalition, has clearly demonstrated the ability to sustain themselves. Though a rag-tag force, the Taliban has hugely benefitted from a ground situation where their ability to blend into the local population remains largely intact.

Consequently, the periodic attacks on high-profile and key targets in Afghanistan by the Taliban and their allies says much about the direction that the Afghan war has taken.

While Cameron cannot be faulted for hosting the Chequers meeting in support of a good cause, Britain itself is clearly on a reverse mode from Afghanistan. Without the confirmed determination of any country to stay the course, making a difference to the way the Afghan conflict eventually gets settled will remain largely uncertain.

Faced with difficult odds, it is important for US President Barack Obama to agree to negotiate directly with the Taliban. In doing so, Washington will need to deepen a partnership with Pakistan’s military-led security establishment.

Given the mounting controversies surrounding Zardari, any move to enlist him as a player will likely backfire at a time when his ability to deal with the many challenges surrounding his own country remains in serious doubt.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.