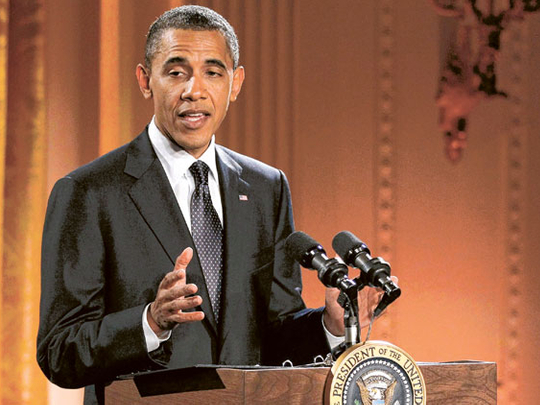

The Americans have dealt the cards once again in the latest version of Afghanistan's Great Game. President Barack Obama has set a course for the drawdown of US forces that is not likely to be reversed.

Afghanistan's close neighbours — Pakistan, India, China, Russia, and Iran — must now decide whether to play on or fold. By most accounts, there has been US military progress in several Afghan provinces, but no one bets it's permanent. For almost a decade, Afghans have demonstrated they cannot fix their country, even with American blood and treasure.

Now the stakes become potentially huge for these regional players. American public support for prosecuting the Afghan war is evaporating. Osama Bin Laden has been killed and Al Qaida's leadership has been hammered. Restive Nato allies want out as well. What will develop in the vacuum left by the withdrawal of US and Nato forces?

There could not be a more opportune time for these regional superpowers to join together in a conference on Afghanistan. Based on common concerns and shared interests, its agenda should be obvious: combating terrorism spawned in Afghanistan and Pakistan, curbing drug production and trafficking, and opening regional borders to commerce and energy pipelines that could greatly enrich all parties.

The difficulty, however, is that not all the parties are likely to agree on what constitutes a good settlement. Shuja Nawaz of the Atlantic Council notes, "China wants a stable Afghanistan. It wants stable neighbours and markets for its goods in central Asia. It wants access to Afghanistan's copper and rare earth minerals. And it does not want a spillover of militancy spawned in Afghanistan and Pakistan."

One would think China an ideal partner for Washington as US interest in Afghanistan ebbs. The Chinese tend to focus exclusively on their own unilateral interests and don't wish to be seen cooperating too closely with the US lest they expose themselves to the wrath of terrorism.

Russia remains unhappy with US bases so close to its southern border, but Moscow also does not want Afghanistan to lapse back into its traditional chaos and "old night," according to Rick Inderfurth of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. He believes the Russians would prefer a slower withdrawal of US troops from the Afghan theatre.

Wild card

If Obama's reduction of the US presence in Afghanistan pleases US voters, it's causing some discomfort among Afghanistan's neighbours. India, which has been battling terrorism much longer than the US, is also understood to prefer a slower drawdown of US forces during ongoing efforts to stabilise the region.

And despite its current abysmal relationship with Washington, Pakistan is also anxious about any downsizing of US forces in Afghanistan. Wracked by a Taliban insurgency within its borders, Islamabad is ever haunted by the US abandonment of the region after Soviet forces retreated from Afghanistan in 1989. Inderfurth believes that "Islamabad is hoping for the best and seeing the worst".

The wild card, however, is Iran. Foreign policy realists like former US secretaries of state James Baker and Henry Kissinger have argued Iran must be brought into the process. That, however, would probably trigger a Saudi demand that they also be included if Iran is involved in any conference on Afghanistan.

Yet Tehran has a demonstrable record of mischief, and one can but wonder whether the current Iranian regime would have anything beneficial to bring to the table and what its demands would be in return for playing a constructive role.

Admittedly, the obstacles are formidable. No one appears especially eager to help Obama out of the Afghan tangle. Pakistan, for example, could take a short-term view and fall back on a strategy of fomenting trouble in Afghanistan in the name of tribal fraternalism with Pashtun tribes.

Still, there is modest reason for hope. A regional agreement on Afghanistan is hugely preferable to living with a failed narco-terror state as one's neighbour — and regional powers must sense the urgency of the situation as US and Nato forces prepare to withdraw.

— Christian Science Monitor

Walter Rodgers is a former senior international correspondent for CNN.