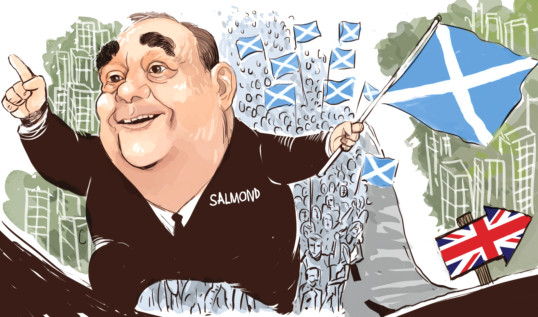

Support for Scottish independence is rising. No one should be surprised. Britain’s unionists have been fighting a technically competent but emotionally empty campaign. Alex Salmond’s Scottish Nationalists have been tapping into a deeper well.

Five months ahead of September’s referendum, the rest of the UK has yet to wake up to the possibility that Scotland could well vote to end its 300-year-old union with England. There is little awareness of the profound shock that secession would deliver to the political, economic and social architecture of the UK or to its stature in the wider world. To say England would be diminished by Scotland’s departure is gravely to understate the consequences.

Britain is sleepwalking towards a break-up of the union even as David Cameron’s English Conservatives dream of wrenching it out of Europe. Britain’s friends in the world — from Washington to Berlin, Canberra to Madrid — look on with bemusement and horror. Can it be that a country once so comfortable with the exercise of global influence is shrugging its shoulders at the prospect of fractured obscurity?

The polls in Scotland, it is true, show the unionists still hold the lead. Surveys of committed voters suggest support for the nationalist Yes campaign is hovering in the low to mid-40s. The unionists command support in the mid-50s. These snapshots belie the dynamics of the debate. All the movement has been in Salmond’s favour. As Britain’s most accomplished retail politician, he has already shown himself adept at snatching last-minute victory from the prospect of defeat.

The campaign is throwing up uncomfortable parallels with the Quebec independence vote in 1995, when the secessionists came from nowhere to within a hair’s breadth of independence from Canada. Starting with barely a third of the vote, the Yes side in Quebec ended up scoring 49.42 per cent — a mere margin of error away from victory. All the energy and optimism in Scotland has come from the nationalists. From the outset, the assumption of the unionists has been that Scots will vote with their wallets. Prove to them that they will be worse off on their own and, hey presto, Scotland will renew its allegiance to Westminster. The result has been a deracinated campaign built on dry statistics and deeply patronising threats. An independent Scotland would have to put up taxes, would be denied use of the pound and be locked out of the EU. The Scots, in short, are incapable of running their own affairs.

Salmond promotes a prospectus that is both flimsier on facts and more powerful politically. His pitch is that Scots should think of what might be if only they cut the shackles of the union. Many of his policies and assertions do not bear scrutiny. No matter. Salmond, a professional politician to his fingertips, has tapped into the contemporary mood of anti-politics. Scotland’s first minister is the plucky insurgent battling the Tory-led establishment at Westminster.

Populist case

In this guise, he has something in common with Nigel Farage, the leader of the anti-Europe United Kingdom Independence party, and Boris Johnson, the Conservative mayor of London whose ambition is to replace Cameron as prime minister. All three are untroubled by hard economic facts or harsh political realities. Their maverick qualities make an easy connection with voters that allows them to shrug off inconvenient truths. In an age of deep mistrust of politics, they contrive to make a plausible, often populist case that they are different.

A Tory-led government in London has been a godsend to nationalists. So too has the opposition Labour party’s habit of sending its brightest stars to Westminster rather than Edinburgh. The Scots have never forgiven the Tories for former prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who saw Scotland as a testing ground for her ideological radicalism. Salmond likes to joke that there are more giant pandas in Scotland than there are Tory MPs. The sad thing is that it is true.

Cameron’s party holds one of 59 Scottish seats in the Westminster parliament. There was a time when it won half these seats. Now, one of the Scottish National party’s campaign slogans tells voters that with a Yes vote in September they could banish for all time any prospect of Tory rule over Scotland.

While Salmond takes a populist low road, his opponents need to locate the high road of unionism. Telling the Scots they would be impoverished will not win hearts and minds — not least because, whatever the initial shock, Scotland has the people and the resources to make a decent living in the world.

Unionism should be a celebration of shared history, culture and enterprise; and an assertion of the advantages of sticking together in a world where power is shifting away from the West. What the unionist side needs is a language for the campaign that brings to life the British heroes forged in a joint endeavour that has been, and is, to the advantage of both nations.

When Salmond claims the Scots must break with England in order to make their way in the world, he defies the plentiful evidence of history. He sounds like Farage calling for Britain to break its ties with Europe. Neither leader can explain how it is easier to make an impact alone than in the close company of friends and partners.

It is not too late to restore faith in the union. But time is running out. I have long thought Cameron’s premiership would find its place as one of history’s less consequential footnotes. I am beginning to fear he will be remembered instead as the prime minister who watched Britain amble into break-up.

— Financial Times