Quetta carnage demands immediate action

It’s time for Pakistan’s establishment to come out of its stupor

The carnage unleashed in Pakistan’s south-western city of Quetta, following a devastating terrorist attack in the past week that killed at least 89 people, has not only raised fresh questions over the country’s security environment, it has also prompted more critical questions on ways in which leaders of the country’s ruling structure have virtually lost all capacity to deal with such powerful challenges.

A week after last Saturday’s attack in Quetta, President Asif Ali Zardari or Prime Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf are still absent from the scene, having given condemnatory statements from a distance. Typical of their style, the two top leaders dispatched a team of members of the parliament to deal with the fallout from the carnage, when members of Quetta’s Hazara community began protesting by refusing to bury the dead.

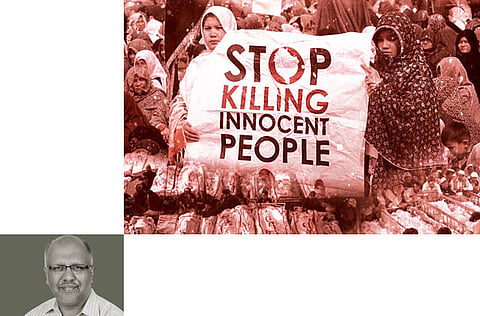

This form of resistance, which must qualify as a unique measure of protest in Pakistan, suddenly spread across the country like fire. Soon, protests were triggered elsewhere too, including Karachi, where life practically came to a halt while life in some parts of Islamabad was also grounded. In the end, the protesters had most of their demands met. Yet, the carnage this month — which followed a similar carnage also in Quetta in January, when more than 100 people were killed — gives few assurances to suggest that a similar breakdown will not recur in the future.

These two attacks are indicative of Pakistan’s continuing security challenges, more than a decade after the country joined the US-led war on terror. However, the situation has clearly aggravated in the past five years since Zardari led Pakistan through a historical transition to democracy. Under his watch, the ruling structure of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) has made little headway in key areas, like firmly establishing a new national security policy with consensus among the key political parties and with the backing of the parliament.

Consequently, Pakistan is locked in a terrible situation where one hand does not know what the other is up to. The dangerous dimension to this difficult situation is indeed that while there is broad agreement across Pakistan’s civil society on the need to combat the menacing effect of terrorism, there is little by way of a nationally recognised strategy with the parliament’s backing through a documented strategy on how best to deal with it.

Meanwhile, the protests which followed the latest carnage have indeed exposed Pakistan to the troubling and challenging question of having to deal with the public fallout to another unfortunate tragedy. For the militants responsible for destroying Pakistan’s body fabric, there must be some consolation from having disrupted the broad society with the fallout. For them, there are indeed more powerful incentives now to repeat this particular brutal form of terrorism with large-scale casualties, than ever before.

Ironically, in an election year, Zardari and those around him should be concerned about taking steps to improve their prospects. However, they have chosen to instead practically abdicate their responsibilities in favour of short-sighted and in some ways futile and petty politics. Winning elections may be the ambition of every politician. However, in the process, ignoring the plight of the people and instead opting for measures like controversial economic policies to gain popularity, just do not pay off. Over the past five years, while Pakistanis suffered on multiple fronts, the government preferred to simply sit on the sidelines and preserve the status quo. With this mindset, it is hardly surprising that the priorities of the ruling elite have taken them more towards areas like resisting calls for Zardari to face fresh investigations in Switzerland on allegations of corruption, than overseeing a concerted push to deal with vital matters of national interest.

Going forward, it will just not be surprising if Pakistan’s election campaign this year turns out to be among the bloodiest in its history. Already, there are warnings from intelligence officials of violent attacks that are likely to take place once the campaign gets underway. If so, by now, Zardari and the rest of the ruling elite should have undertaken to initiate a concerted, broad discussion among key politicians for organising as relatively risk-free a campaign. However, in line with the style of the ruling hierarchy, the effort seems to be focused more on agreeing upon a new prime minister who will be least threatening to the main political players. Indeed, Pakistanis have every right to say that the country is stuck and unable to progress, especially after another large-scale carnage in the city of Quetta.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.