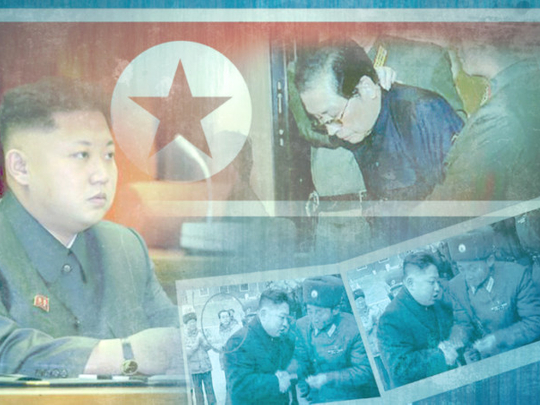

North Korea is a place where whispers of negativity about the leadership can get one thrown into a gulag for life. Even so, the brutal and swift execution of Jang Song Thaek, the uncle of leader Kim Jong-un, was unusual. Before this very public event, every analyst of this opaque country believed Jang would continue interminably as the senior regent and the second most powerful man in North Korea, supporting the young Kim.

Boy, were they wrong.

Between the execution of Jang and the purging of General Ri Yung-ho, the top general, in July 2012, the young Kim appears to be striking out on his own. Yet it is not clear what his power base is.

North Korea’s first leader, Kim Il-sung, favoured the party over the military in building his personality cult. The second, Kim Jong-il, chose military over party. But this brash young 30-year-old is alienating both institutions and the vast networks of cronies attached to stalwarts such as Jang and Ri. That is bold, but it is also risky.

We can only guess at what this all means. Jang’s execution is the likes of something we have not seen in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) since the early 1950s, when a young and inexperienced Kim Il-sung — handpicked by Stalin and unknown to the North Korean people — ruthlessly killed all his competitors. Perhaps Kim Jong-un associates his own struggle with that of his grandfather. In any event, these latest events confirm the regime’s turn to a hardline, fundamentalist ideology by the young Kim, not one of opening and reform, which analysts believe Jang came closest to representing.

Jang’s purge indicates that a power struggle of regime-rattling proportions is taking place inside the North. The government’s statement described Jang as organising resistance with party and military officials, and youth leagues in conjunction with outside influences. This is an incredible admission from a country that associates stability with its hermetically-sealed borders.

Where this will lead next is unclear. Palace politics suggest that the whereabouts of Kim Kyong-hui, the leader’s aunt and husband of Jang, is a critical indicator. She, who is known to be in poor health, appears to be the sole remaining senior regent of the Kim clan — junior Kim is almost on his own.

China’s conspicuous silence

This could mean he will be more cautious, or it could mean effective adult supervision over the brash young leader is ending. Regardless, few experts today see a more stable North Korea as a result of the execution and more are worried about things unravelling from here on out.

China has remained conspicuously silent about the events. Jang was clearly their man and their window into the opaque regime. Indeed, Beijing’s distancing from the junior Kim after the DPRK’s third nuclear test earlier this year was only possible because the Chinese leadership could transact business through Jang. Now, the US must convince China not to double-down. China must resist the temptation to seek an early face-to-face with the junior Kim to protect its own stake in resource extraction and other enterprises in the North. This would confound the quiet but effective continuing cooperation between the Obama White House and Xi Jinping’s Beijing administration to incrementally dial up the sanctions against Pyongyang until it cries uncle and comes back into compliance with denuclearisation agreements.

The only thing certain about the new North Korea under Kim Jong-un is its unpredictability. Indeed, on the day of Jang’s execution, the DPRK reached out to South Korea regarding cooperation on a long-frozen joint industrial complex. Only days earlier it released without explanation an American tourist after a month’s detainment.

So fasten your seatbelts. Public executions of top leaders is not the last of the surprises we may see coming out of Pyongyang. In that regard, if Jang’s purge is a sign of desperation rather than confidence by the young leader and palace politics starts to unravel, the cycle of provocations we see routinely from the North may seem tame compared to the threat of a destabilised rogue, nuclear weapons state.

— Financial Times

Victor Cha, the author of The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future, is a professor at Georgetown University and served on the US National Security Council from 2004 to 2007.