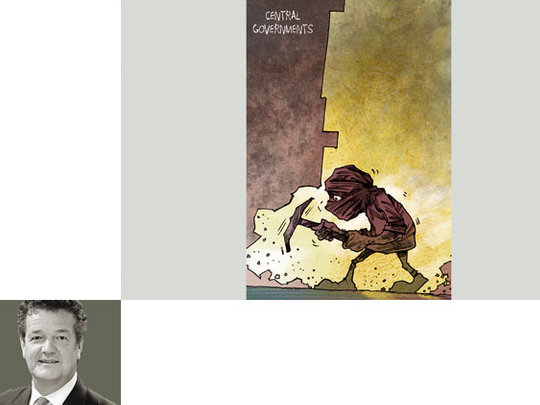

Nation states look very neat on the map, with their borders well-defined by thick lines, each country shaded in one colour, showing how each state is different from its neighbours. Such maps give a clear impression that each nation state is a coherent unit, and the authority of the capital runs throughout the territory.

The reality can be very different. Some plunge into civil war as their political strains fail to be managed by the central government, and others quietly accept substantial autonomous control in particular regions. The Middle East is surrounded by nation states that are not in full control of their territory.

Iraq is the most obvious example, where the Baghdad government does not control the affairs of the Regional Government of Kurdistan. Both sides insist that Kurdistan is part of Iraq, and it suits the Kurds to pretend that is the case. They would face major problems from Turkey and Iran if they declared their independence. They are also tied to Baghdad for the present by pipelines that take their billions of dollars of oil through Iraq to their customers in the outside world.

Pakistan has large areas in its northwest called Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), which are not really administered at all and are left to the traditional government of the tribes in the area. For decades this was a forgotten issue, but in recent years Islamabad’s weakness in FATA has become a major problem.

Even Iran, which is seen as a Persian-speaking unitary state, includes a large number of substantial non-Persian peoples, like the Baluchis in the south-east on the border with the Pakistani province of Balochistan, and the Azeris in the north-west on the border with Azerbaijan and Armenia. In both these territories, local authorities have substantial room for manoeuvre, which is a matter of enduring concern for Tehran.

Lebanon also has internal challenges to strong central government. Hezbollah has refused to disarm, and still maintains its own semi-state functions in the south. In addition to its political, security and military roles, Hezbollah also maintains hospitals and schools, runs large parts of the country, and keeps the loyalty of its people.

These cases of controlled and accepted breakdown of central control are an inspiration to many would-be local leaders in Syria. As the new Syrian National Coalition wins more and more international support, any predictions for 2013 have to include the possibility of Bashar Al Assad’s government falling and a weak transitional authority taking over. This is good news for an ambitious local leader in the Kurdish area around Qamishli in the north-east, or in Jebel Druze in the south, or maybe even an Alawite government loyalist trying to see a way forward as his government fails, and is dreaming of once again flying the flag with the Gold Star of the Alawite state of the 1920s and 1930s in the Alawite heartland around Latakiya.

The incoherence of the Syrian opposition means that the fall of the government will be messy, and any transition will be confused. The 50,000 or so troops who are fighting in over 100 units are only now starting to come together into a vaguely unitary command structure under the Syrian National Coalition. But even the Free Syrian Army under the previous Syrian National Council only controlled about half the forces on the ground, and its ‘control’ was only nominal in many areas.

Strategic management

This lack of strategic management has been spotted by many outside forces anxious to gain from the breakdown of strong government in Damascus. Perhaps the most open has been the Kurds in the autonomous Kurdish Regional Government, where President Masoud Barzani has already given military training to several thousand young Syrian Kurds so that they can play a role in “protecting their native land and maintaining security within it”, according to his website Payamner. Barzani has also supported setting up the People’s Council of West Kurdistan in the Qamishli area of north east Syria.

There have been many reports of units of trained and experience Islamist fighters going to fight the government, and presumably to take advantage of whatever they can find as the state collapses. Some of these tough military units are not even Arab, offering the possibility that Afghan or Chechen groups are following orders from radical visionaries outside the country.

Such international and regional forces will have non-Syrian agendas. The Kurds would love to build a series of Kurdish regional areas across Iraq, Syria, Iran and Turkey, with a long term dream of using them as the building blocks of a future state. The Islamists probably do not have territorial ambitions, but would like to insert themselves more dominantly into the Syrian body politic.

The people who lose out in all this are the many millions of ordinary people, who have fled for their lives, and fear for their property. They want to return to a normal existence, quietly getting on with the careers and see an end to the increasingly brutal civil war which is deeply damaging Syria.