Iran, West show signs of thawing

With tough posturing gone for now, the new round of nuclear talks brings promise of a compromise deal

Iran and six world powers have concluded their much-awaited meeting in Istanbul with an agreement to hold yet another meeting in the Iraqi capital on May 23. In a marked contrast to their previous encounters though, this round of talks began in a positive atmosphere as both sides had been signalling a willingness to listen and make compromises on the basis of mutual respect and equality. As such, it was no surprise when lead negotiators from both camps described the occasion as "useful", "constructive", and "positive".

As the two sides appear to be making an "encouraging progress" in bridging their differences, therefore, a temporary agreement between Iran and the international community is highly plausible as each side will likely try to first weigh the other's intentions, end goals, and indeed steadfastness before reaching a major agreement.

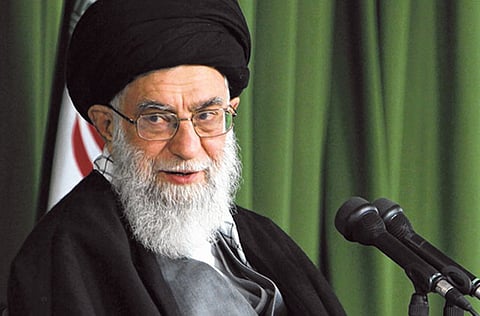

Today, Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is firmly in charge of the majlis, the judiciary, and the armed forces, and thus he is confident that his authority will not be challenged from within even if he was to forgo his anti-Americanism. Put differently, as Khamenei continues to tighten his grip on state apparatuses, Tehran might, rather ironically, soften its stance on the nuclear issue and make some meaningful compromises in return for lifting of some of the sanctions; an issue that was reportedly high on Iran's agenda in Istanbul. In this way, not only can he ease the public anger and buy his regime legitimacy, but also hope to cause a rift, however minor, in Washington-Tel Aviv relations since Israel will be highly sensitive to any deal that allows Iran to continue with its enrichment activities even at below the 5 per cent threshold.

The key reason behind such assertion is Khamenei's recent remarks in which he has practically praised US President Barack Obama for managing to warn both Iran and Israel about his intentions, and advocating diplomacy as a solution to Tehran's nuclear ambitions. In an important sense, his remarks could be interpreted as a sober attempt to create a political cover for an eventual deal with the West, helping his regime to avoid being seen as capitulating to US demands. This becomes all the more likely when one takes into account Khamenei's decision to extend former Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani's political career by retaining him as the head of the Expediency Discernment Council. In what seems to be a well-thought-out move, Rafsanjani has since been advocating talks with the US, thereby enabling Khamenei to gain an understanding of the elite, if not the public, perception on such eventuality without losing face.

Public uprising

Meanwhile, Western powers' initial optimism over the possibility of a public uprising and a subsequent regime change in Iran caused by economic privation is gradually but surely eroding. Not only Iran's internal security forces have successfully suppressed the opposition, but there is also a profound, albeit unspoken, disconnect between Iranian youths' national and personal hopes.

As the so called "engines of revolution", a large number of Iranian youth have their eyes fixed on the West, dreaming to leave and live their lives elsewhere. They argue that it takes generations to rebuild Iran, and that why should they suffer for political mistakes of "the revolution generation" many of whom are now living a comfortable life in Europe and North America. Add to these 33 years of aggressive so-called Shiite indoctrination and it then becomes clear why the reign of Ayatollahs may be far from over.

There is also a bitter realisation among Western leaders that although sanctions can slow Iran's progress in the nuclear field, they are nonetheless unlikely to undo the nuclear know-how which Tehran has accumulated over the years. As Iran's neighbours and Israel's patience for a meaningful outcome from sanctions runs thinner, as a result, Western powers have good reasons to seek a deal with the current regime even if it comes at the expense of democracy and human rights in Iran.

Surely, this is not to suggest that a deal is now imminent, and that Iran's nuclear standoff with the West is reaching its final episode. Far from it, there is still way to go before the two sides can reach a comprehensive agreement. Given Iran's strategic interest in having a "substantive" nuclear programme as a form of deterrence and a sign of prestige and national power as well as the profound mistrust between Iran and the West, the current momentum can be easily lost. This is not to mention that a transformative decision is likely to be postponed until after US presidential elections.

Yet, given the overall scheme of regional and global developments, and the inevitability of an Israeli strike in the absence of a deal in Baghdad, there are grounds for cautious optimism that a tactical and/or temporary compromise could be arrived at in the next meeting, especially if discussions are framed in the context of "commitments against rights" whereby Iran would be allowed to keep some enrichment activity in return for absolute transparency and unconditional fulfilment of its nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) obligations.

Nima Khorrami Assl is a security analyst at Transnational Crisis Project in London

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox