India’s democratic pageant

As the victors in May cobble together a government, their challenge will be to sustain a pluralist nation of competing ideas

Last week on March 5, India’s independent Election Commission announced the dates for the next general election. The world’s largest single exercise of the democratic franchise will take place over a staggering 37 days in nine “phases,” some a week apart, from April 7 to May 12. Some 814 million eligible voters will elect, for the 16th time, a new parliament and government, casting their ballots at more than 930,000 polling stations — after choosing from an estimated 15,000 candidates belonging to more than 500 political parties.

Democracy, of course, is a process, not an event. But India’s elections —with their outsized logistical and security challenges, myriad languages, and candidates identified not just by name but also by electoral symbols to aid illiterate voters— are events that evoke admiration each time they occur.

It takes a sizeable forest to furnish enough paper for posters, electoral rolls, and ballots. And the thousands of electronic voting machines that are manufactured in India can survive heat, dust, and power failures — and retain their results safely until the votes are ready to be counted, sometimes weeks later. (Because no votes are counted until the last ones are cast, counting day is May 16.) Moreover, every election has at least one story of officials battling through snow or jungle to ensure that the preferences of remote constituents are duly recorded.

Yet there are larger issues behind the electoral spectacle that must not be overlooked. India’s elections have, over the years, deepened and broadened the composition of the political establishment. Sociologists have analysed the class composition of India’s legislatures and traced the change from a post-independence parliament dominated by highly educated professionals to one populated by today’s motley crew of MPs, who are more truly representative of India’s rural heartland.

But the fact that, particularly in India’s northern states, voters elect people referred to openly in the press as “mafia dons,” “rogue leaders,” and “anti-social elements” is a troubling reflection on the way the electoral process has served Indian democracy. In the last four parliaments, at least a 100 members have had criminal cases pending against them. The resulting alienation of the educated middle class means that fewer and fewer of them go to the polls on Election Day.

The poor, however, do. Whereas psephological studies in the United States have demonstrated that the poor do not vote in significant numbers (presidential-election turnout in Harlem averaged 23 per cent before Barack Obama’s two candidacies), the opposite is true in India.

In India, it is the poor who take the time to line up in the hot sun, believing that their votes will make a difference, whereas more privileged voters, knowing that their views and numbers will do little to influence the outcome, have been staying at home. Studies of Indian elections have consistently shown that the poorest vote in numbers well above the national average, while the educated middle-class turn out in numbers well below it.

Means to break free

The significant changes in the social composition of India’s politicians and bureaucrats since Independence are indeed proof of democracy at work. But many lament that the poor performance of the country’s political class in general offers less cause for celebration.

India’s parliamentarians increasingly embody the qualities required to acquire power rather than the skills needed to wield it for the common good. Many cynics regard democracy in India as a process that has given free rein to criminals and corrupt cops, opportunists and fixers, murderous musclemen and grasping middlemen, kickback-making politicos and bribe-taking bureaucrats, mafia dons and private armies, caste activists and religious extremists. And yet it is democracy that has given Indians of every imaginable caste, creed, culture, and cause the chance to break free of their lot. Where there is social oppression and caste tyranny, particularly in rural India, democracy offers the victims a means of salvation. Among the victors in recent elections have been people from traditionally underprivileged backgrounds who have risen through the power of the ballot to positions their forefathers could never have dreamed of. There could be no more startling tribute to the Indian system.

Yes, elections also allow many to vent extreme views. There are those who wish for India to become a Hindu Rashtra, a land of and for the Hindu majority; those who wish to raise even higher the protectionist barriers against foreign investment that have started to come down; and those who believe that a firm hand at the national helm would be preferable to the failures of democracy.

As the victors in May cobble together a government, their challenge will be to sustain a pluralist India of competing ideas and interests, unafraid of the power or products of the outside world, and determined to liberate and fulfil its people’s creative energies. I have little doubt that the democratic process will ensure inclusiveness rather than fragmentation. The only possible idea of India is that of a nation greater than the sum of its parts.

In India, as elsewhere, there will always be a choice between a world of edicts and crusades, where orthodoxies rule and foreign heresies are ruthlessly suppressed, and a world in which the virtues of tolerance, dissent, and cooperation are recognised and practiced. As it goes to the polls, India, with a sixth of the world’s population, should offer an instructive example of the latter.

— Project Syndicate, 2014

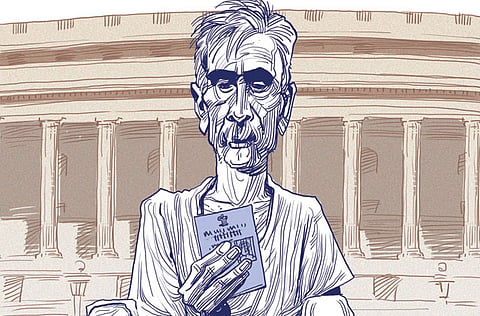

Shashi Tharoor is India’s Minister of State for Human Resource Development. His most recent book is Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century.