The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the world's major arms control agreement — now 40 years old and signed by 189 states — is in a deep crisis. Can it be rescued and, indeed, can it be reinforced to meet the challenges to international security in the coming decades?

This will be the task of the NPT review conference, due to be held in New York from May 3-28 — one of the most important dates in the nuclear calendar.

There are, unfortunately, no great expectations that the conference will make the world a safer place. There is simply too much mistrust surrounding everything to do with nuclear weapons — mistrust between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states, between those who abide by the rules and those who are suspected of breaking them. The truth is that secrecy, double-dealing and hypocrisy have long characterised the nuclear game.

The NPT was created on the basis of a three-sided bargain:

- Five nuclear weapon states — the US, Russia, the UK, France and China — committed themselves to getting rid of their nuclear weapons. This disarmament remained, however, a vague aspiration rather than a concrete pledge. When it was supposed to happen was never spelled out.

- In turn, non-nuclear weapon states who signed the NPT pledged not to acquire nuclear weapons — although some of them then sought to do so clandestinely, under the cover of the treaty.

- As a reward for their pledge to foreswear nuclear weapons, they were promised access to nuclear fuel and technology for peaceful civilian purposes. But such access has, all too often, been denied.

In a word, the grand bargain on which the NPT rested was more often breached than observed. Today, it seems in danger of collapsing altogether — and nowhere more so than in the Middle East.

The situation at present is that the first five nuclear weapon states have not really disarmed at all, and show no serious intention to do so. US President Barack Obama's speech at Prague in April 2009, in which he promised "America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons" — what has come to be known as his call for "global zero" — has not yet been reflected in practical politics.

Admittedly, the US and Russia have agreed to some cuts — and put their signatures to a new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (Start) earlier this month — but their nuclear arsenals remain vast. This is not disarmament as it was meant to be.

Another blow to the NPT has been the behaviour of North Korea. It signed the treaty but then proceeded to acquire nuclear weapons clandestinely — and to test them. Faced with international outrage, North Korea withdrew from the NPT, and has since been treated as a pariah.

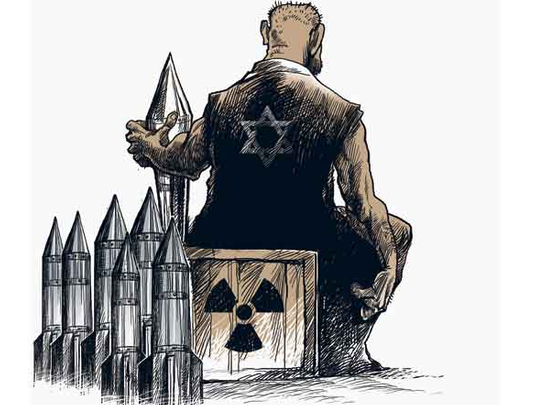

Three other countries have dealt a still more serious blow to the dream of disarmament, non-proliferation and access to nuclear technology for peaceful purposes. Israel, India and Pakistan have all built nuclear weapons and have refused to join the NPT. Evidently, the existence of the treaty did not prove an obstacle to their accession to nuclear status. They have suffered no unwelcome consequences as a result of their proliferation, not even a word of reproof.

Playing favourites

Quite the contrary: although Israel went ‘nuclear' in the 1960s, it has benefited ever since from lavish American financial and military aid, as well as unstinting political support. The US has steadfastly refused even to raise publicly the question of Israel's nuclear arsenal. As a result, Israel has been able to maintain a nuclear monopoly in the Middle East, which it no doubt considers a key element in securing its regional military hegemony. It has repeatedly used force to prevent other states in the region from acquiring nuclear weapons.

India and Pakistan have also escaped censure or sanctions on account of their nuclear activities. Instead, India has recently been granted privileged access to American nuclear fuel and technology, while Pakistan, a close American ally in the struggle against the Taliban, has been a recipient of substantial US financial aid.

Such preferential treatment has by no means been extended to Iran, since its determination to master the uranium fuel cycle has led to suspicions that it is secretly attempting to build nuclear weapons — or at least acquire the technical ability to do so at speed in an emergency.

Iran is a signatory of the NPT and has allowed its facilities to be inspected regularly by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Its leaders have repeatedly denied that they are seeking nuclear weapons. Nevertheless, they claim the ‘inalienable right' to use nuclear energy for civilian purposes — a right which is indeed afforded them by the treaty.

But this has not protected Iran from the threat of more sanctions and even of military attack. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been working hard to mobilise international support for a UN Security Council resolution imposing tough sanctions on Iran. These sanctions are intended, she says, to convince Iran to begin genuine "good faith" negotiations on its nuclear programme.

Someone should perhaps suggest a new approach to Clinton, one which might offer Iran incentives rather than threats. Iran might, for example, be more conciliatory if it were offered security guarantees — especially against an Israeli strike.

It might respond favourably on the nuclear issue if the US were to encourage the Gulf states to include Iran in a regional security pact. Iran's anti-American and anti-Israel rhetoric would certainly be softened if Washington were able to persuade its Israeli ally to allow the emergence of an independent and viable Palestinian state.

The Middle East is widely seen as a crucial area for global security. Obama should persist in his efforts at conciliation with Iran — and with the world of Islam in general — and not allow himself to be pushed off course by hawks in Israel and Washington.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs.