The international community has rightly condemned the brutality of the Syrian regime’s response to the peaceful expression of legitimate aspirations for democratic reforms and fundamental freedoms.

Last week the United Nations human rights office released a report stating that in the confrontation between government forces and the pro-democracy protesters in Syria 2,900 people have been killed.

An Amnesty International report concluded that “human rights violations committed against civilians… in Syria, amount to crimes against humanity.” The report recommended that the UN Security Council refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court.

The harsh crackdown on the protesters and the bloody result is transforming what started as peaceful demands for democratic reform, on the Egyptian revolution model, into an armed conflict, on the Libyan model.

The comparison with Libya is instructive. Like the events in Libya the bloody confrontation in Syria may develop into a full blown civil war. But unlike Libya, a civil war in Syria fuelled by ethnic conflicts carries with it the distinct possibility of igniting other ethnic conflicts and further destabilising the region.

While the revolution in Libya may not have been characterised as a vital interest of the US, the events in Syria clearly can affect Washington’s vital interests in the region.

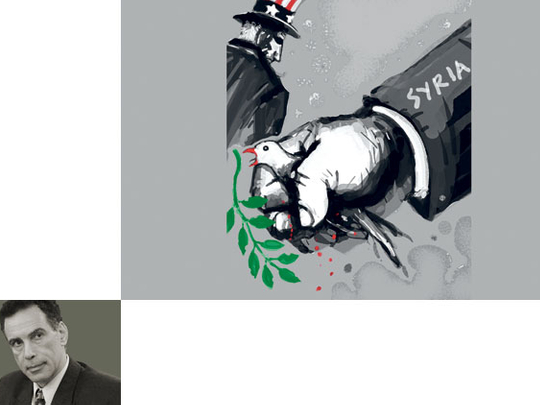

The overriding interest here would be to prevent local conflicts from threatening the traditional American vital interests in the Middle East, namely: Access to strategic resources in the region and the maintenance of a regional military balance of power that is favourable to Israel.

It was to defend these interests that Washington went to war against Iraq —twice. Once in 1991 to eject Iraqi troops from Kuwait; and again in 2003 to forcibly remove Saddam Hussain from power and end his threats to the Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, on the one hand, and to Israel’s military hegemony in the region, on the other hand. Ironically the neo-cons in the Bush administration, pursuing common goals with Israel, had targeted the Syrian regime as next Arab candidate for regime change, to put an end, once and for all, to all possible Arab challenges to Israeli military domination in the region.

Although as a military power Libya pales into insignificance with Nato’s military might, it took Nato months and thousands of air strikes to subdue Libyan military defence, and pave the way for Libyan opposition to take power.

But Syria is not Libya, and even on grounds of humanitarian intervention, it would be hard for Washington to find support domestically and internationally for a Libya — like the bombing campaign against Syria. The most logical reason for opposing such a war against Syria is the difficulty of keeping it localised. Another imponderable would be the reaction of Israel and the temptation to grab more land from Syria.

One more reason why the military option against Syria is not viable is the absence of any clear leadership for the pro-democracy movement, or for the opposition.

Whatever opposition there is remains rhetorically committed to change but effectively unable to bring it about. In Syria, the question is not whether the opposition is armed or not, the question is: Who are the opposition? And how effective are they as a political force? And are they capable of popular mobilisation to support a programme of democratic reforms and economic revival?

It was not until last week that the fragmented Syrian opposition managed to establish a broad-based national council committed to overthrowing President Bashar Al Assad’s government.

Obama too wants to overthrow Al Assad’s regime. The question is how? The New York Times reported last month that the Obama administration had decided that the Al Assad regime would not survive the sustained challenge of the protest movement. The administration, the paper reported, had begun to prepare for the post-Al Assad regime.

In particular, Washington is concerned about the possibility of a civil war among Syria’s ethnic and religious groups (Alawite, Druze, Christian and Sunni sects) and its potential impact on the region.

But Washington may be repeating the mistakes of its unfortunate experience in Iraq. In its obsession with regime change and the forcible removal of Saddam, it failed to develop adequate strategies to prevent the post-Saddam Iraq from descending into violent chaos.

What is already clear is that Washington has decided that Al Assad must go. But it is not clear what plans there are, if any, for the post-Al Assad Syria.

Obama has called on him to step down and the US is currently discussing “how to help bring it about.”

In other words, the Obama administration is currently discussing how to bring about regime change in Syria in the absence of an open military intervention. Washington has opted for a strategy of punitive economic pressure on the Al Assad regime.

Shutting the European market to which Syria exports 90 per cent of its oil exports, could cripple the Syrian economy. But it may not necessarily bring the regime down. Those Syrians already suffering from high unemployment and chronic poverty are already in revolt. The business elites and the middle class were supportive of Al Assad’s liberalisation of the economy, and his capacity to think strategically as evidence by his support for the American war on terror.

After the armed uprisings of the Muslim Brothers in Aleppo in 1980 and in Hama in February 1982 were crushed with ruthless brutality, a government general amnesty diffused the threat and fragmented the organisation. The army is infiltrated with Alawite and is a beneficiary of the status quo, although this could change.

The irony is that a new political party law ratified by the Syrian parliament last August could have effectively put an end to the one-party system put in place by the Baathists after they seized power in a military coup in 1963. But it did not, proving that an authoritarian regime cannot reform itself.

Adel Safty is Distinguished Professor Adjunct at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Russia. His new book, Might Over Right, is endorsed by Noam Chomsky, and published in England by Garnet, 2009.