At first glance, it seemed like a great victory for British diplomacy — after months of haranguing our European allies about the need to take a stand against Vladimir Putin’s adventurism, last week Europe finally found its collective spine and did something. Unfortunately, tempting as it might be to think that Britain had suddenly rediscovered some clout in the world, there was little or no causal link between British and US demands for Europe to act, and Europe actually doing so.

For weeks before the shooting down of MH17, Britain had vocally backed US demands for meaningful European sanctions, and got virtually nowhere in the face of implacable French, Italian and German national self-interest. Even three days after the airliner and its passengers had crashed to the ground, in private both US and British officials in Washington professed little hope that Europe — forever demanding Obama show more “global leadership” — could find the political resolve to confront the Russian menace in its own back yard.

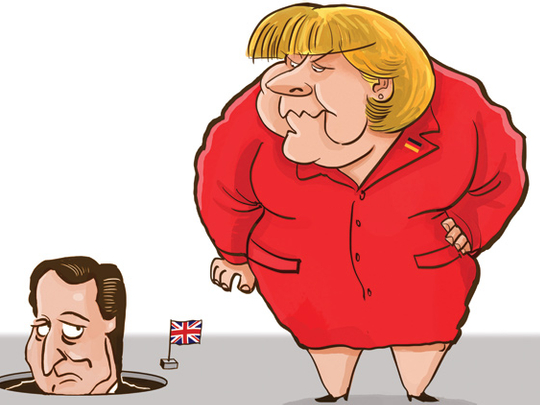

So who, or what, suddenly unlocked the door on sanctions? Was it Cameron’s shaming of the French over arms sales? Or possibly George Osborne’s public pledge that Britain, unlike France, was prepared to accept some economic “pain” as the price of taking a principled stand against Putin? According to those familiar with the negotiations, there was indeed a world leader who single-handedly broke the European sanctions deadlock — Angela Merkel, the German chancellor.

“She got angry,” said a source close to the negotiating table, and quite suddenly what had been impossible to achieve in four months of Anglo-American diplomacy got done in a weekend. There were many factors at play, but ultimately it was Merkel’s ire that moved the needle. Once Germany had made its decision, the other pieces rapidly fell into place.

The Dutch, as the nation that lost most, added their voice and with the Brits already on side the French and the Italians, after securing a couple of face-saving exemptions, had no choice but to fold their objections. Washington was as surprised as it was relieved at Europe’s change of heart. Until last week, Putin had always appeared one step ahead of the bickering Eurocracy, expertly playing one off against the other with last-minute concessions. However, sources in Washington say he made two fatal miscalculations — first, he failed to return several of Merkel’s phone calls and second he interrupted the German leader’s holiday — and everyone in the US knows how much we Europeans love our summer vacations.

“There are some red lines in international diplomacy that you just don’t cross,” went the joke among jubilant US officials, “and one of those is disturbing Mrs Merkel’s holiday plans.” The note of frivolity conceals a very serious truth: Britain occupies a diminished position in Washington’s European pecking order these days.

When it comes to transacting really important transatlantic business, the Germans hold the key. Not that Britain’s vocal support is unappreciated in the White House — the Brits received a pat for being “steadfast from the start” and a “useful outlier” in the sanctions negotiations — but inevitably, Merkels’ transformative power only serves to highlight the limits of British influence in Europe. In some ways, Britain is a victim of her own faithfulness.

Our loyalty is taken for granted by successive US administrations — on defence, on free trade, on sanctions — whereas Germany, prickly and independent-minded, needs to be wooed, and receives attention accordingly. Indeed, it speaks to the fundamental importance of Germany as Europe’s indispensable nation that presidents Merkel and Obama still manage to work together, “stovepiping” the awkward aspects of their relationship, such as CIA spying antics or Germany’s historic unwillingness to spend more on defence.

The fact that Britain is also seen as having one eye on the exit door in Europe does not help our cause in Washington since — as France’s economic problems mount — Germany becomes the obvious long-term hedge for the US against a British decision to leave.

US officials also see Britain sparring openly with the French and Italians, and wonder whether the UK, even inside Europe, now has much long-term use. At one point in the sanctions negotiations, I understand, a fractious Italian diplomat demanded to know if Britain was “already out”. Similarly, when they see David Cameron grandstanding over the appointment of Jean-Claude Juncker, or before entering a European Council meeting, US officials privately say they see a lightweight leader more interested in playing to the galleries back home than getting the job done. By contrast, when Merkel speaks, Washington and the world still listen.

The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2014