US President Barack Obama, who told the American people on August 28 that his administration does not “have a strategy yet” to deal with the threat of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isil) seems to have got one now. Yet, regardless of the details of the strategy — announced on Wednesday — it would not have been possible for the Obama administration to declare war on Isil without the removal of Iraq’s former prime minister Nouri Al Maliki and the formation of a more inclusive government in Baghdad.

Indeed, it took the Obama administration years to come to the conclusion that the very presence of Al Maliki on top of Iraq’s political system was the key factor that had led to the resurrection of Al Qaida and affiliated groups in Iraq. The capturing of wide swathes of territory in the north and west of Iraq by Isil would not have been possible were it not for Al Maliki’s divisive sectarian policies, which have compelled Iraq’s marginalised Sunnis to take up arms and support extremist groups fighting the Iraqi military and police forces. Only then did the Obama administration decide that Al Maliki was no longer fit for the job.

For four years, Washington has been fooling itself and everybody else by claiming that Al Maliki was doing a good job. It turned a blind eye to his flagrant sectarian policies and argued that Iraq under Al Maliki’s leadership was relatively stable. All it needed was a little bit more training, weapons and logistical support and everything would be okay. At the forefront of Obama’s policy objectives at the time was that under any circumstances, the US would not get militarily involved in Iraq one more time.

Obama knows that his promise to withdraw all American troops from Iraq by 2011, revitalise the economy and curb militarisation were the key factors that had led to his election in 2008. His national security strategy, known as the “Obama doctrine” stated that he would only approve the use of force if US vital interests were threatened. In cases where these interests were not in clear and present danger, the response would be through the use of agile, unconventional forces, or drones and the provision of training, intelligence and logistic support for local allies.

With the focus on the withdrawal of troops from Iraq, and efforts to distance itself from the legacy of the Bush era, the Obama administration chose to ally itself with Al Maliki notwithstanding his rampant corruption and sectarian policies. Even after the March 2010 elections, which gave a clear victory to former Iraqi prime minister Eyad Allawi, Washington supported Al Maliki’s endeavours to stay in power for fear of Iran trying to sabotage Obama’s withdrawal plan. The revolt of the Sunni Arabs of the Anbar province against Al Maliki at the end of 2012 did not change the mind of the Obama administration.

In a late attempt to prevent the advances of Isil extremists across the border from Syria into Iraq, Obama agreed to supply the Al Maliki government with state of the art military technology including the AH-64A Apache, the US army’s primary attack helicopter. Obama thought that a victory by Al Maliki against Isil would deal a blow to his critics and add substance to his doctrine, which favours providing material and training support to allies in lieu of sending direct combat forces.

In return for the provision of military support, the Obama administration requested that Al Maliki be more open to his political opponents, not only Sunni Arabs and Kurds, but also those within his own ruling Shiite coalition — requests Al Maliki ignored.

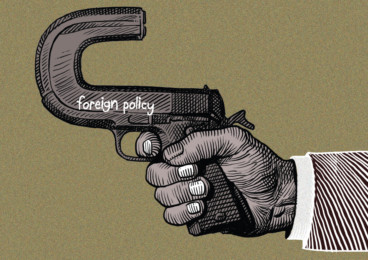

The rapid collapse of the US-trained and equipped Iraqi army in the face of Isil in Mosul relegated the Obama doctrine to the dustbin of history. Iraq was turned from being Obama’s greatest success story into a prime example of his foreign policy failures. His critics argued that his arbitrary withdrawal from Iraq left the stage open for America’s enemies to wreak havoc in the country. A similar scenario might occur in Afghanistan, where American forces are expected to withdraw later this year. The possibility of the Taliban and Al Qaida filling the power vacuum resulting from the withdrawal of American forces is by no means farfetched.

Against this grim backdrop, Obama dragged his feet back to the region to fight Isil not only in Iraq but also in Syria. The killing of hundreds of thousands of Syrians in a bloody and ugly conflict did not seem strong enough reason for him to intervene. Isil, which has risen from the ashes of Syria’s neglected conflict and set alarm bells ringing throughout the globe, will make him do what he has been reluctant to do for four years now.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is a Syrian academic and writer