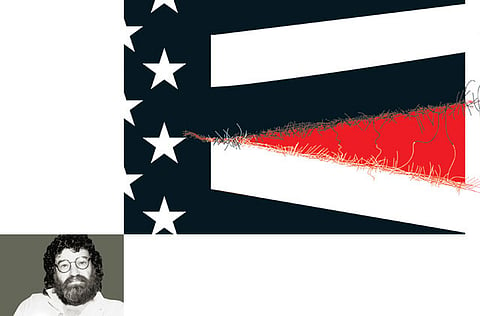

America’s post-racial challenge

It is clear that the issue of race in America is still unresolved

Those engaged in the debate — on both sides of the divide — about the degree to which race played a role in the George Zimmerman trial have, well, continued to hold their ground.

In an impromptu briefing at the White House late last week, President Barack Obama tried to explain the disconnect between how white and black Americans have reacted to the verdict by a jury whose predominantly white members acquitted the defendant of the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager in February of last year.

“I think it’s important to recognise that the African-American community is looking at the issue through a set of experiences and a history that doesn’t go away”, he said, touching on the nation’s still unresolved history of race relations. And as if to define his own personal place in that history, he added: “There are few African-American men who haven’t had the experience of being followed in a department store and that includes me”.

“There are very few African-American men who haven’t had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of car”, he continued. “And that happened to me, at least before I was senator. There are very few African Americans who haven’t had the experience of getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off. That happens often”.

Is it really that bleak for black folks in America? Hasn’t well over half a century of civil rights struggle culminated with men being judged — as Martin Luther King put it in his iconic “I Hav A Dream”

speech in 1963 — not by the colour of their skin, but the content of their character?

The euphoria that surrounded the election of Obama as president had commentators trumpeting the idea that Americans now lived, at long last, in a post-racial society. The de facto motto of the US — E Pluribus Unom (from many, one)— has finally been redeemed.

That, however, remains a matter of debate.

In 1865, the population of the US was made up of 35 million whites and 5 million blacks, with nine-tenths of the latter living in the South, where they toiled as slaves creating wealth for their masters by producing sugar, rice, tobacco and cotton. After Reconstruction, they became, in the quaint idiom of the time, “freedmen”. Today they number 43 million and live in every state of the Union.

The question, though, remains: Though blacks have been freed of their shackles, how freed have they become of their sense of “otherness”, the feeling that others see them as apart? It is a question that the African-American critic, novelist and poet Richard Wright raised in his book, Black Boy. “And the problem of living as a negro was cold and hard. What was it that made the hate of whites for blacks so steady, seemingly so woven into the texture of things?” he asked. “What kind of life was possible under that hate? How had this hate come to be?”

True, Wright’s sentiments were written in the 1950s, but they, in a sense, found their echo in Obama’s improv speech at the White House last week. Has much changed since Wright wrote?

Admittedly, in the last several decades, the US has moved forward, with “people of colour” seizing opportunities that had been denied before government-sanctioned discriminatory laws were struck down through Congressional legislation and Supreme Court rulings. African-Americans today are in finance, journalism, the film industry, the world of academics, the halls of Congress and, well, the Oval Office itself. And yet society remains polarised along racial lines, with both blacks and whites continuing to play “the race card” — in the words of Carrie Bess, to feel that “we’ve got to protect our own”.

And who, pray tell, is Carrie Bess? She was a single black woman with grown children who was a member of the predominantly black jury — in lawyerly code words, a “downtown jury” — that acquitted O.J. Simpson of the charge of murder in 1995.

As in all trials involving juries composed predominantly of blacks or whites, race pervaded every moment of the Simpson trial — and perhaps even the crime itself. Race was, it is now clear, at the heart of the proceedings. (That this element is evident in American jurisprudence raises serious doubts about the efficacy of the jury system, wouldn’t you say?)

Conversely, look at the case in March 1991 of four white LAPD police officers who had been videotaped beating the bejesus out of Rodney King, an African American construction worker, who were acquitted the following year by a predominantly white jury (ten whites, one black and one Latino) of aggravated assault, despite the clear evidence of the defendants’ culpability. The acquittal, as we all recall, triggered the 1992 race riots in Los Angeles, in which 53 people were killed, more than 2,000 injured and 6,345 arrested.

Again, in 1992, ten black and two white jurors acquitted Washington, DC, mayor Marion Barry, who had been caught on tape, in an FBI sting, smoking crack cocaine, of all but one of the 14 narcotic charges brought against him. And going further back still to 1955, the two white men charged with murdering Emmet Till, a black teenager who was “caught” flirting with a white woman, were found not guilty by an all-white jury after about an hour of deliberations.

And so it goes, with this phenomenon of “protecting our own” not limited to celebrated cases. Off the bat, consider the borough of the Bronx in New York City where juries are 80 per cent black and where black defendants are acquitted 47.6 per cent of the time, which is about three times the national average.

As Robert Shapiro, one of the lead defence lawyers in the Simpson trial (dubbed “the trial of the century”) openly and brazenly put it to Barbara Walters: “Not only did we play the race card, we dealt it from the bottom of the deck”.

Judging by the clenched fists, the symbolic hoodies and the angry talk at Trayvon Martin rallies all across the country, it is clear that the issue of race in America is still unresolved. America still has a lot of soul-searching to do. The journey from holding your ground to giving ground will be long indeed.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.