Two years since the Syrian revolt began, , the results are there for all to see: more than 70,000 dead, one million displaced, a country destroyed. Hundreds of jihadists have descended on a country — from Afghanistan, Iraq or Libya — whose regular army, like it or not, is still in command. There is a stalemate militarily. The core of Damascus is still under the control of the Bashar Al Assad regime. He can easily convince an increasingly tired population how life was better some years ago.

“In no way can the rebels win, write it down in your magazine, they are not going to win!” former Iranian foreign minister Ali Akbar Velayati told Politique Internationale. The Syrian army still has enough materiel; local militias supporting the government are increasing in number and foreign allies – the presence of Iran’s Al Quds units was even confirmed by the Pasedaran Major General Mohammad Ali Ja’afari — will make up for the rest.

The Syrian National Coalition and ranting members can do little in the face of a deadlocked situation. Before it implodes (the Muslim Brotherhood core was absent from the recent Rome meeting), the SNC goes on saying that “it will never start discussions unless preliminary conditions are met”.

The Al Assad regime, on the contrary, seems now to be prepared for talks, but nobody wants to talk with it. Meanwhile, arms are being poured into the country, so that more Syrians can die.

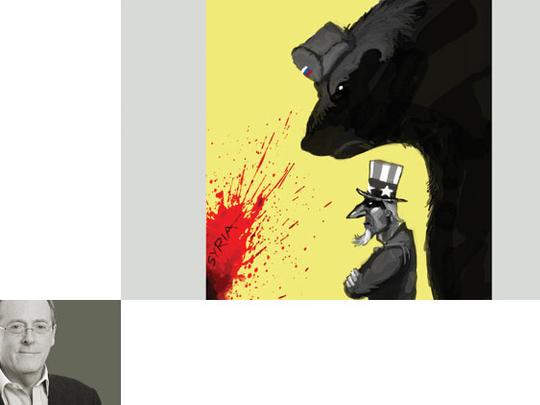

How long can this go on? Russia and the US have, of late, started showing increasing signs that, maybe, enough is enough. Two major threats are indeed emerging.

It is too late to do anything about the first threat. Iran’s role has reached such a level that one cannot see how the country could not be part of any future settlement. Fighting Iran by proxy, as some had imagined, has come back to haunt them. Assuming that the major preoccupation for some Arab states was protection from Iran, there probably was no worse move than pushing Al Assad into Tehran’s arms. The Iranians have now become inseperable partners of the Syrian regime.

The second threat is an increasingly serious risk of the regionalisation of the conflict. Lebanon will bear the brunt of this — and this is beyond the 300,000 Syrian refugees who have streamed into it. The violence has spilled over into the country, as we have seen in Tripoli or in the Bekaa Valley. Then there are people like the cleric Ahmad Al Assir, who is playing the usual game when trying to get arms: “Our Sunni brothers are being murdered by Bashar’s army; give us arms to defend ourselves!”

How long will the weak Najeeb Mikati government be able to keep the peace in a country where Syria has traditionally had a strong role. The murder of Lebanese General Wissam Al Hassan comes to mind.

We should also remember the fact that Syrian refugees now number one million.

And what about a possible extension of the conflict with Israel, on the issue of the Golan? Or renewed Hezbollah activity in South Lebanon?

Many Syrians believe the bad blood between communities is so deep the country will never recover from it. Yet, external risks have become dangerous enough to make some major players think it is time to end the conflict.

Europeans continue to favour the Syrian National Coalition route. But it is clear that the collection of jihadists, deserters, genuine freedom fighters and exiled, talkative intellectuals would lead nowhere.

A recent development at the Paris-based Arab World Institute illustrated the widening gap between politically correct do-gooders and what should be a pragmatic foreign policy.

The Arab League already demonstrated some months ago its pathetic response. Whatever the reasons, some Arabs thought it judicious to help destroy another Arab state instead of concentrating on other targets.

The Arab failure to bring peace to Syria has paved the way for a Russia-US solution. The Russians have already received coalition leader Muath Al Khatib and the Americans will receive National Coordination Haitham Manna’s friends in Washington in mid-March.

Secretary of State John Kerry has confirmed the US wants a political settlement and Russian President Vladimir Putin doesn’t make Al Assad’s fate a key issue: he knows his departure alone would solve nothing.

What is now required is to stop killing people, enforce United Nations control and impose a dialogue. Those who persist in feeding the conflict with arms know it can last for years. Considering the risks, Russia and the US won’t wait that long.

Luc Debieuvre is a French essayist and a lecturer at IRIS (Institut de Relations Internationales et Strategiques) and the FACO Law University of Paris.