As an uprising gathered momentum in Palestine, I sat for hours listening to and recording the story of Ahmad Al Haaj, an 83-year-old Palestinian refugee from the village of Al Sawafir who has been living in Gaza since 1948. My feelings swayed between the memories of the past and the bloody reality of the present.

The defining event that led to his exile was the defeat of Beit Daras, a southern Palestinian village inhabited by fellahin, poor peasants who fought to the last bullet. “The Zionist militias’ convoys eventually returned, this time with vengeance. They made their expected move against Beit Daras on June 5, 1948. They struck at dawn and charged against the village until the early afternoon. By placating the stubborn Beit Daras, the entire structure of local resistance was likely to fragment and collapse. The village was surrounded from all directions, and all roads leading to it was cut off to ensure that fellahin fighters didn’t come to the rescue. Although by then the fighters in Beit Daras had acquired up to ninety rifles, the invading militias amassed an arsenal of modern weapons, including mortars, machine guns mounted on top of fortified vehicles and hundreds of fully armed troops.

“The militias moved in, executed whoever survived the initial onslaught, civilians and all. The rest escaped running through burning fields, tripping on one another while being chased by sniper bullets. The massacre stilled fear and horror, especially as the death toll had reached 300 in a village population that once barely totalled two thousands.”

A People’s history of Palestine is a theme that has permeated all of my books and most of my articles for years. Ever since I took on the task of recording this narrative, I have been confronted with that same feeling, time and again: Regardless of who is telling the story, regardless of the time and place of events that unfolded and regardless of the demography of those being chronicled, ordinary Palestinians have been essentially retelling the same story for generations.

Few outsiders have actually listened or bothered to connect narratives — to unite Gaza, Jenin, Deir Yassin, Dheisheh, Sabra and Shatila, Yarmouk, Jabalaya and a thousand other tragic references — into a cohesive intellectual and historical unit that cannot be separated or selectively analysed.

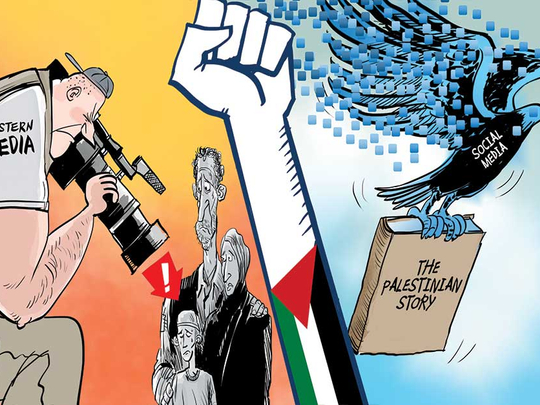

But while the Palestinian story has maintained its obvious links and integrity after all these years, mainstream Western media’s misconception and misconstruction of the Palestinian narrative has also maintained its deficiencies and overall failure. It continues to see Palestinians as aggressors, injecting the same old tired terminology to support its haggard discourse, and insulate itself from those who refuse to adhere to its poor standards.

When my book Searching Jenin was published soon after the Israeli massacre in the Jenin refugee camp in 2002, I was questioned repeatedly by the media and many readers for applying the word ‘massacre’ to what Israel has depicted as a legitimate battle against camp-based ‘terrorists’.

The interrogatives were aimed at relocating the narrative from a discussion regarding possible war crimes, to a technical dispute over the application of language. For the media, the evidence of Israel’s violations of human rights mattered little.

This kind of reductionism has often served as the prelude to any discussion concerning the so-called Arab-Israeli conflict: Events are depicted and defined using polarising terminology that pays little heed to facts and contexts, and which focuses primarily on perceptions and interpretations.

Isra’ Abed, aged 28, was shot repeatedly on October 9 in Affula, and Fadi Samir, aged 19, was mercilessly mowed down by Israeli police a few days earlier. Despite tragedies such as these, the media’s reductionist attitude clearly indicates that it hardly matters whether or not such Palestinian youth were, in fact, knife-wielding Palestinians or not.

Even when video evidence emerges countering the official Israeli narrative and proves, as in many other cases, that the murdered youth posed little or no threat, the official Israeli narrative always takes precedence. Thus, Isra’, Fadi, and the scores of others who were killed in the last two weeks are ‘terrorists’ who endangered the safety of Israeli citizens and, alas, had to be ‘eliminated’ as a result. The same goes for the over 600 young Palestinian men and women who have been detained during this period.

The same logic has been used throughout the last century when the current Israeli army, still operating as armed militias and organised gangs in Palestine, before it was ethnically-cleansed to become Israel. Since then, this logic has applied in every possible context in which Israel has found itself: It was allegedly, “compelled” to use force against Palestinian and Arab “terrorists” and potential “terrorists” along with their “terror infrastructure”.

Indeed, much of our current discussion regarding the protests in occupied Jerusalem, the West Bank, and as of late, at the Gaza border is centred on Israeli priorities, not Palestinian rights, which is clearly prejudiced. Once more, Israel is speaking of “unrest” and “attacks” originating from the ‘territories’, as if their priority is guaranteeing the safety of the armed occupiers — soldiers and extremist colonists, alike.

Israeli rationality, it seems, would be the opposite of a state of “unrest” — “quiet” and “lull” achieved only when millions of Palestinians agree to being subdued, humiliated, occupied, besieged and habitually killed or, in some cases, lynched by Israeli Jewish mobs, or burned alive, while embracing their miserable fate and carrying on with life as usual.

The return to “normality” is thus achieved, obviously, at the high price of blood and violence, which Israel has a monopoly on, while its actions are rarely questioned. Palestinians are thus expected to assume the role of the perpetual victim, and their Israeli masters to continue manning military checkpoints, stealing land and building yet more illegal colonies in violation of international law.

The question now ought not to be basic queries about whether some of the murdered Palestinians wielded knives or not, or truly posed a threat to the safety of the soldiers and armed colonists. Rather, it should be centred principally on the very violent act of military occupation and illegal colonies on Palestinian land in the first place.

Unlike the 1987 Stone Intifada, when mainstream media reigned supreme, or even the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000, when social media was yet to morph into its current status and influence, this time around, the Palestinian story must be told — and fairly so.

The current Intifada in Palestine cannot be understood separately from the past, or reduced to simple terminology pertaining to a failed peace process and other media talking points. It is a rebellion that is rooted in a much deeper and larger context and that has to be appreciated in its entirety.

Dr Ramzy Baroud has been writing about the Middle East for more than 20 years. He is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. His books include Searching Jenin, The Second Palestinian Intifada and his latest is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story. His website is: ramzybaroud.net.