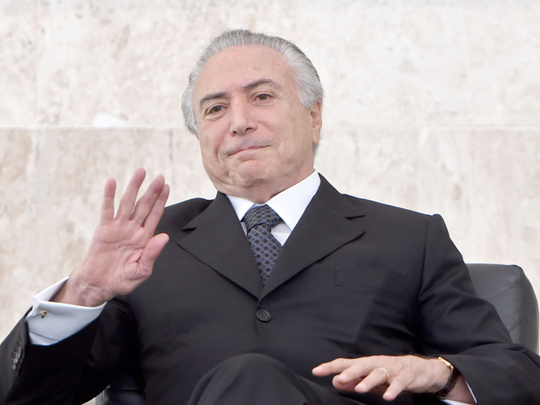

For anyone expecting new management to save Latin America’s richest nation from economic debacle and political paralysis, you might need to wait a bit. Barely had Brazilian Vice-President Michel Temer taken over from the scandal-torn government of president Dilma Rousseff — who was charged with budget fraud and ordered to trial in the Senate — than he found himself wallowing in his own mess.

To his credit, Temer wasted no time in firing his planning minister and chief political operator Romero Juca, who was overheard scheming to hasten Rousseff’s impeachment — apparently to shield himself and his political cohorts from the widening probe into graft and kickbacks at the state oil company, Petrobras. By doing so, Temer limited the damage to his unloved provisional government and rescued his emergency austerity plan, which passed Congress after a bruising 16-hour debate that ended after midnight on Wednesday.

Temer is no stranger to the Faustian bargains that Brazil’s national leaders must strike in order to govern. His party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB) has been a part of every government since the return of democracy in 1985 — cutting deals in Congress, occupying aeries in the federal bureaucracy and sharing the spoils of power.

The PMDB is the most successful contender in what may be Latin America’s most permissive political ecosystem, which encourages parties to divide, multiply and nourish at the public trough — voters be damned. Just when Brazil’s electoral system became unintelligible, as the late political scientist Amaury de Souza put it, is hard to pinpoint. But blame falls partly on its Supreme Court. In 2006, the high bench struck down a “performance clause” benefiting parties that met a 5 per cent polling threshold. If that had stood, Brazil today might have six or seven reasonably sized political parties, reckons Octavio Amorim, a political analyst at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Rio de Janeiro. Instead, Amorim noted, there are 28 with seats in Congress (up from 22 in 2014), each with the constitutional right to field candidates, grab free airtime for televised campaign spots and claim a share of the taxpayer-subsidised national political parties’ fund.

The result is chronic legislative gridlock and friable governing coalitions, puttied together from a multitude of parties, who swap their allegiance for pork, patronage and — increasingly — payola.

The Petrobras scheme was nothing but a system to keep rentier allies happy by decanting the runoff from inflated public works contracts into campaign coffers. The estimated damage to public finances: More than $10 billion (Dh36.78 billion), including $1.8 billion in bribes alone.

So it’s understandable why Brazilians have so little regard for their elected representatives, and also why deliberations in the Congress can turn into opera bouffe. “Clown”, “punk” and “imbecile” were a few of the qualifiers lawmakers hurled at one another week before last. And this was in the congressional ethics committee, mind you.

Fortunately, not all is lost. Even with the country obsessing over Rousseff’s impeachment, some lawmakers have been busy. Last month, the Senate voted to reform private pension funds, barring political appointees from top positions and requiring the funds to submit to independent auditors. Senators also approved a state company responsibility law to shield government-owned businesses like Petrobras from crony management. In February, they eased nationalist restrictions on private investment in Brazil’s ultra-deepwater “pre-salt” oil fields. All these bills are now before the Lower House.

In a country where the hyperactive executive branch traditionally dominates legislation, such progress is heartening. “Now, with the president weakened by impeachment, the judiciary is filling the vacuum,” Senator Antonio Anastasia, from the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, told me. “Parliament has to show it can take back the initiative.”

Still, Brazil’s political class needs not so much a comeback as an overhaul. Unfortunately, any effective changes — reducing the number of parties, district voting to hold lawmakers more accountable to local constituencies — will have to clear the very politicians who thrive on the current system of indulgences.

With all the emergencies falling on Temer’s watch, that may be a revolution for another day.

— Bloomberg

Mac Margolis is a Bloomberg View contributor based in Rio de Janeiro.