‘Well, he better start fighting for me or he’s gonna be out! I want him to do right, but he must not cut the president!”

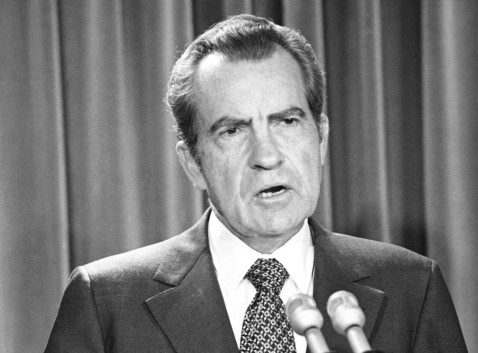

That was Richard Nixon, caught on tape shouting about his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, who had just insisted on his independence during the Watergate investigation. Nixon’s ire was prescient — Richardson would, indeed, go on to “cut the president”. On October 20, 1973, the attorney general very publicly resigned rather than carry out a White House order to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox.

Within hours, Richardson’s deputy, William Ruckelshaus, would likewise refuse to follow Nixon’s command. Cox was finally ousted (then solicitor general Robert Bork did the deed), but not before the ‘Saturday Night Massacre’ reassured some in America that not all the president’s men were deep in his pocket. Americans should be so lucky in 2017!

As the Nixon scandal unfolded, a few prominent Republicans stepped forward to take on the president. Senator Howard Baker, the minority chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities (better known as the Watergate committee), and senator Barry Goldwater famously spoke up in the later stages of the saga. What is little known is that they were preceded by Republican civil servants inside the administration who stood in the way of some of the White House’s most nefarious plans. Without those less-publicised efforts, America could have succumbed to an even more serious constitutional crisis.

List of enemies

In the summer of 1971, the Nixon White House began compiling an enemies list that ultimately included hundreds of Democrats, anti-war activists, reporters and administration critics. The goal, in the words of a memo by White House Counsel John Dean, was “to use the available federal machinery to screw” Nixon’s political opponents.

The worst of what Dean and others contemplated, however, didn’t come to pass. Johnnie Walters, a Republican from South Carolina, was commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service. He consistently fought against the White House’s attempts to politicise his agency. When Walters was given the enemies list, he locked it inside a personal safe because he believed the “Enemies Project” was a serious threat to America’s tax system. With the support of secretary of the treasury, George Shultz, Walters told the White House that he would not move forward with its request to audit those on the list.

“It was an improper use of the IRS, and I wouldn’t do it,” recalled Shultz, in an oral history taped in 2007 for the Richard Nixon Presidential Library.

Well before the enemies list was drawn up, Nixon had campus activists in his sights. He told his advisers he wanted to find a way to cut off federal funding to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and other elite universities as punishment for rampant student anti-war protests. In 1972, as a massive US bombing campaign in North Vietnam reignited protests, Nixon put more pressure on his administration to find a way to punish the schools. “I want those funds cut off, for that MIT,” the president told H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, his chief-of-staff.

The order was eventually relayed to three assistant directors at the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) — Kenneth Dam, William Morrill and Paul O’Neill. Two of the three were registered Republicans (Dam and O’Neill), but all three were united in their opposition to the order and threatened to resign in protest. “There’s no basis in law to carry out this order,” O’Neill remembered when he was interviewed by the Nixon library. Once again, Shultz stepped in, and with his help, the men at OMB successfully blocked the order and kept their jobs.

‘Too many nice guys’

The actions of Republicans like these, who had to say no to Nixon, are evidence that the president’s downfall was not the product of a single misstep or tantrum, but rather a sustained effort to institutionalise abuses of power. Nixon began his second term telling Haldeman and White House special assistant Fred Malek, on tape, that “there must be absolute loyalty” among his staff and inner circle.

“I think the trouble is that we’ve got too many nice guys around who just want to do the right thing,” an exasperated Nixon told his closest advisers in the Oval Office when discussing Shultz’s refusal to help politicise the IRS.

The US survived Nixon because enough good men said no. We can only watch and wait to see whether such heroics will be matched in this administration.

— Los Angeles Times

Historian Michael Koncewicz is the Cold War Collections specialist at New York University’s Tamiment Library. He is working on a book on the Republicans who stood up to Richard Nixon.