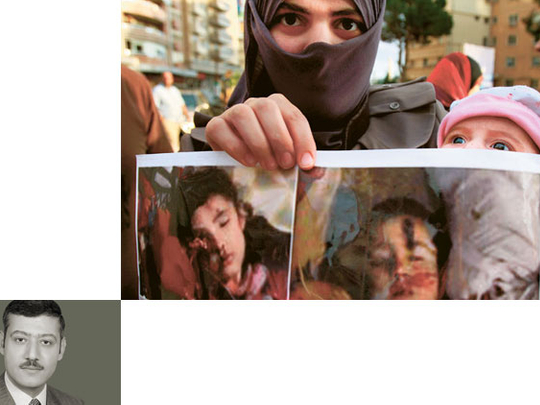

The massacre of at least 108 villagers in the town of Al Houla, 15 miles northwest of the central Syrian city of Homs, might indeed constitute a turning point in the 15-month-old Syrian uprising. The heinous crime has generated an unprecedented wave of outrage and condemnation world-wide. For the first time since the beginning of the protest movement in March 2011, the UN Security Council (UNSC) has unanimously passed a statement that condemned the killings and called for bringing the perpetrators to justice.

Although the statement was not as strong as it should have been, getting Russia and China — typical supporters of the Syrian regime — on board was important development.

For more than a year now, these two permanent members of the UNSC, particularly Russia, have rejected any international effort, including verbal condemnation, to pressure the Syrian regime to stop using violence in dealing with the protest movement. It is still too early though to talk about a real shift in Moscow’s position on the crisis.

Another major development that was prompted by the Al Houla massacre was the expulsion of top Syrian diplomats from more than ten EU countries and the US, Canada and Australia. These measures may have been intended to strengthen Kofi Annan’s stand during his presence in Damascus for talks with the Syrian regime.

These developments are indeed important. Yet, from a realistic point of view not much has truly changed on the ground. The Annan peace initiative has shown no sign of ushering in an end to more than 14 months of violence. On the contrary, the crisis has, in fact, taken a more complicated trajectory than ever before. In the two months since the regime and the opposition agreed to the Annan plan, the UN observers could not secure the end of violence, let alone start a dialogue between the conflicting parties. The two sides have different interpretations of every single one of the six points of the plan, especially the last one, which calls for dialogue between the regime and the opposition.

The regime believes it has already carried out the required reforms to satisfy the protesters and insists that no talk will be held with the so-called “outside” opposition, namely the Syrian National Council (SNC), since it has been calling for foreign military intervention and is thus “unpatriotic”. The opposition believes that there is nothing to discuss with the regime besides transfer of power. How Annan is going to bridge the gap between the two sides is anyone’s guess.

In fact, there is little hope that the Annan plan can stop further deterioration of the situation on the ground. Nevertheless, nobody is willing to call the initiative dead yet because it is the only political proposal in hand and the alternative, for many, is civil war. But for civil war to occur, a balance of power must exist in which the two sides wield approximately the same amount of power. That is not yet the case in Syria. But as the conflict drags on, that situation might not last.

So many powerful players are already participating in the Syrian crisis that the regime and the opposition are increasingly on sidelines. Syria is small, but too important to be lost. Hence, the stakes are high for regional and international powers and the competition is fierce. Given the highly complex nature of the conflict, the regional and international polarisation and the world economic crisis, the appetite for foreign military intervention is low. That might come as good news for the regime supporters. Yet, the alternative is war by proxy. That is already the case in Syria, where all the foreign powers, regional and international, with a stake in the conflict seem to be willing to fight until the last drop of Syrian blood.

Annan’s plan will not get anywhere because it is a recipe for regime demise. Foreign military intervention does not seem probable. The regime, after more than 14 months of harsh crackdown, could not crush the protest movement, let alone bring the entire country back under control. Similarly, the opposition has learned that slogans, amateur videos, peaceful demonstrations, media pressure and limited skirmishes here and there do not bring down a regime.

Nevertheless, the regime does not seem willing to move beyond the cosmetic changes it has already made. The opposition is adamant about bringing down the regime, but does not know how. It seems therefore that a low-intensity conflict will continue for some time. Until a viable alternative emerges, foreign powers are willing to tolerate this situation, but it is the Syrians who are paying the heaviest price.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is the dean of the Faculty of International Relations and Diplomacy at the University of Kalamoon.