Britain’s referendum will, in the end, be a test of common sense and values. That the British electorate may be getting ready to commit an act of national self-sabotage by choosing to pull out of the European Union is something that baffles many Europeans. It scares those who care about democracy. But those who, on the contrary, promote intolerance are full of hope that it will happen — witness the statements made by France’s Marine Le Pen.

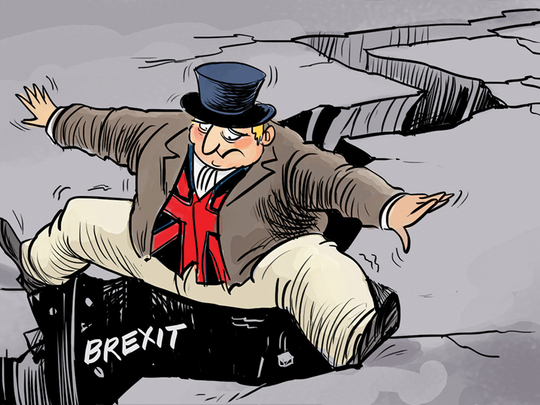

Just months ago, no one expected it would come to this. Now everyone is watching British people putting at stake the very survival of the United Kingdom and the stability of the economy, in a move that would send toxic ripple effects across Europe.

Most people watching from the continent are bewildered. No one is discovering out of the blue that Britain has always had a particular approach to the European project, drawn from its history and its taste for “the open sea”. But problems have piled up for Europe in recent years, and the possibility that a key member of the union may now fall out of it promises severe uncertainties for everyone. The march to Europe’s disintegration would not just rattle institutions, treaties, economic growth, trade — it would threaten democratic values, the essence of what we are supposed to stand for.

If Britain drops out, there will be efforts to limit the damage. EU leaders have already started discussing the reassurances they would give that the European project, created to harness peace and solidarity, will live on, even without Britain. Expect solemn declarations and well-choreographed summitry. But deep down, everyone will know that something essential will have been lost. That’s likely to have important consequences, and it’s hard to be certain that Britain wouldn’t be affected over time.

I can already hear the objections: Britain’s democracy is hundreds of years older than the 1957 treaty of Rome, and joining the bloc in 1973 was never meant to protect heritage — it was all about drawing economic advantages. Democracy in Europe was anchored through the defeat of Nazism and then by the US security umbrella provided during the Cold War. Saying Brexit would suddenly make democracy unravel across the continent is alarmist. Nor is the EU a beacon of democracy. Its institutions have often been criticised for their “democratic deficit”. Not to mention that some member states — namely Hungary and Poland — have been sliding into illiberalism and autocratic politics.

Institutional flaws

Let’s take those points in reverse order. It’s true democratic governance has faltered in several EU states, and that the union as such was unable to prevent that from happening: Hungary’s and Poland’s governments were, after all, democratically elected. But the union’s rules are the first and main mechanisms that can, and should, be leveraged to get those countries back on a democratic track.

It’s EU membership that provides the safeguards, and that’s what many Hungarian and Polish democrats are counting on. Many of the EU’s democratic flaws have less to do with its own institutional set-up than with the choices national governments have made, whether on Eurozone governance or on the migration issue: remember that the heart of power in the organisation is the European Council, where heads of state and governments gather — not technocrats.

The European project may not be perfect, but its very existence has done much to spread democracy on the continent. It acted as a magnet for Greece, Portugal and Spain when they rejected dictatorship. It deployed soft power to help reform countries that broke out of communist totalitarianism. It should continue to exert — although this effort has slowed — a powerful influence on Balkan nations that fought devastating wars until just over 15 years ago, and are now hoping to be allowed into the club. Britain’s role in much of this has been crucial.

The referendum campaign has focused on immigration statistics — the obsession of Brexiters — but the wider picture is that European reunification has been a historical accomplishment, something that those who remember the 1970s or 1980s could never have predicted.

Democracy is easily taken for granted. In my country, France, Britain has often been described as a spoilsport, blocking high-minded European federalist projects, but these days French politics isn’t exactly a model of democratic stability, nor of “European spirit”, with the rise of the far right and an ongoing state of emergency. Europe is plagued by populist, xenophobic movements that have capitalised on the mismanagement of the migration crisis and on years of middle-class disgruntlement with globalisation and the recession. Britain is unique, but not so unique. Its politics resonate in many ways with what is going on in the rest of Europe. A recent Pew study shows a massive drop in support for the EU across member states since 2015, when more than 1 million people arrived in Europe. Today, fewer French citizens (38 per cent) than British citizens (44 per cent) view the EU favourably.

Make no mistake, there are external actors hoping to see the EU collapse, for which Brexit might be a catalyst. They see the EU as decadent and weak. What Brexit would do is deliver a devastating blow to all those who want to protect whatever is left of moderate, common-sense views in Europe — and send an encouraging signal to extremists of all stripes. It would weaken the mechanisms that have been created to protect tolerance and decency. The EU is fundamentally about democracy and individual freedoms. It’s the timing of the UK referendum, not just the polls, that makes it so worrying for many Europeans. If it had been held in 1986, 1996, or 2006, when circumstances were very different in Europe, it wouldn’t have been the potential earthquake it has now become. In none of these other decades was democracy under such threat as now, both inside and outside Europe. Authoritarianism and the appeal of strong men have been on the rise in important parts of the world. The EU has a unique global voice to defend democracy — if only because as an entity it never invaded anyone and it was never a colonial power. If Britain separates from it, both the EU and Britain will lose that clout. As the UK referendum approaches, the first place to worry about democracy is in Europe. That’s because we live in an era of hyper-connectedness. Discourses of prejudice and nationalistic hubris resonate across borders instantly. What happens in one country can undermine the moral dimension of the whole European Union, and decisively so. This is not about budgets and technocracy, it’s about values. That’s the first reason why democrats in Europe would like remain to win.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Natalie Nougayrede is former executive editor and managing editor of Le Monde.