Romney’s Bush-style foreign policy

Romney himself struggles to remember what he actually believes in

A cynic inspecting Mitt Romney’s foreign itinerary of Poland, Israel and Britain might mutter: “Polish vote, Jewish vote, Olympics.” But there is also a genuine philosophy behind Romney’s choice of destinations.

The Republican candidate’s main critique of Barack Obama’s foreign policy is that the president has spent too much time courting America’s enemies and dissing its friends. Under the Obama administration, according to this argument, loyalty and long-term friendship with the US is rewarded with the cold shoulder. Anti-American posturing, by contrast, is rewarded with an apology and concessions. So Obama has made elaborate speeches in the Muslim world, but not visited Israel. He has pursued a reset with Russia, but has been accused of cavalier treatment of the Poles and Balts. And he has stressed relationships with rising powers in Asia, while allegedly neglecting old alliances, such as the “special relationship” with Britain.

Romney’s foreign itinerary is intended to drive home this argument. It is a pointed tour of old friends and allies.

Not all parts of this critique make equal sense, though. While Nile Gardiner, one Romney adviser, has made a fetish of compiling lists of alleged slights to Britain by the Obama administration, most of these have failed to register with the British themselves. In stark contrast, Romney managed genuinely to offend many Brits with some unguardedly frank comments, before his visit to the Olympics. (The most successful event ever staged in the history of the world, and let no foreigner ever suggest otherwise.)

Romney is on surer ground when he suggests that the president has antagonised traditional allies in Israel and Poland. Obama has not actually done much to pressure Israel, but he has a famously frosty relationship with Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister. As for the Poles, they were upset by America’s shift of position on missile defence and reacted fiercely when Obama recently referred to “Polish death camps” in the Second World War. (The approved formulation is Nazi death camps in occupied Poland.)

Romney’s people also argue that the gains from Obama’s courting of former foes have been feeble. The Russian reset is in danger, now that an angry Vladimir Putin has returned to the Kremlin. America’s popularity ratings in the Muslim world are still dismal. Early Obama ambitions to work closely with China have not worked out.

So Romney has the beginnings of a case to make. The trouble is that the implication of his argument is a promise to return to the Manichean world view of George W. Bush — in which nations are divided firmly into friends and enemies of the US and policy is set accordingly.

Romney has already called Russia, America’s “number one geopolitical foe”, and promised to designate China a “currency manipulator” on his first day in office — a move that could be a prelude to trade sanctions. In Israel, over last week, he came close to encouraging an attack on Iran.

Those who yearn for a US foreign policy based on a Bush-style “moral clarity” and the confrontation of autocracies might thrill to all this. The implications are alarming, however: War with Iran, trade war with China, confrontation with Russia.

Obama’s emphasis on diplomacy, even if it is difficult, is preferable to a foreign policy based on biffing “bad guys”. Talking to the Russians and trying to avoid war with the Iranians does not mean that you lack a moral compass or are “weak”. It simply means that even if you have no illusions about the regimes you are dealing with, you try to find ways of living with them, as long as they last.

Some Republican ultras argue that the president’s approach is driven by a “third word list” rejection of western values. A more plausible view is that Obama is, in fact, a foreign policy realist whose views are rather similar to those of Republican centrists such as Brent Scowcroft and Colin Powell.

The futility of dividing countries into camps of “good” and “evil” is underlined by the vital and complicated US relationship with Pakistan. On the one hand, the Pakistanis seem to have played a double-game over Al Qaida and the Taliban, which should place them firmly in the “evil” camp. On the other hand, Pakistan has sometimes worked closely with the US over Afghanistan and it is a nuclear-armed state that is threatened by militancy. The US needs to talk to the Pakistani leadership, however infuriating and untrustworthy it may sometimes seem to be.

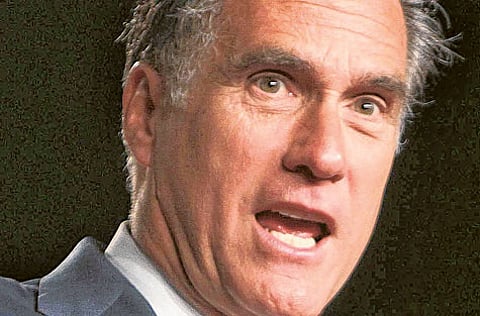

Does Romney believe in all this “good” and “evil”, moral clarity stuff that he is tossing out for the Republican faithful? Who knows. I suspect that, after years of campaigning, Romney himself struggles to remember what he actually believes in. My guess is that his inner core, if he has one, would incline him to a coldly pragmatic foreign policy rather close to that of Obama. Romney is an establishment man and his campaign does not suggest he is driven by unbending principle.

The trouble is that campaign rhetoric cannot all be wiped away, like an Etch A Sketch, the moment the candidate wins the White House. Romney is currently staking out positions that would pursue him into office — to the detriment of America and the world.

— Financial Times