If you want to know how young adults in the United States are detached from their modern history, then consider my encounter with one such millennial the other day. “Sad”, I noted, “the death of Father Berrigan, isn’t it?”

“Father who?” came the addled response.

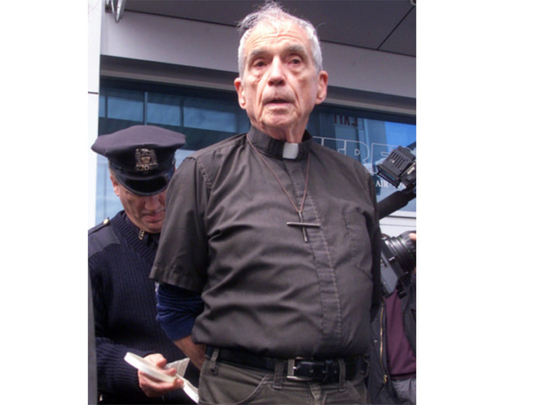

Those of us who lived in that zestful decade we call the “Sixties” and flatter ourselves on having contributed, however modestly, to its cultural effusions, learned many lessons from the example set by Father Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest, author, poet, teacher and virtuoso peace activist, who became a major figure in the anti-war movement in the 1960s and early 1970s, and left his stamp on the era. One of those lessons? Stand your ground and speak truth to power, even if that posture came with a heavy price tag.

In 1968, for example, a year characterised by not-so-decorous disruptions by peace activists, that included the massive protests outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the takeover by students of Columbia University in New York, Father Berrigan, accompanied by his brother, Father Philip Berrigan, along with seven other anti-war activists, entered the Selective Services office, in Cantonville, Maryland, gathered hundreds of draft files, took them outside, and burned them to ashes.

The Cantonville Nine, as they became known, were arrested, tried and convicted of “destruction of government property”. Father Berrigan was sentenced to three years in jail. Instead of reporting to the authorities, after all his appeals had failed, he taunted them instead by going underground, where he stayed for four months, dodging FBI agents. However, he found time, and the audacity, to speak at a church in Philadelphia, where he told the congregation at 1am: “We have chosen to be branded peace criminals by war criminals”. (He ultimately was captured and made to serve his sentence — minus one year for good behaviour.)

It was neither the first nor the last time that Father Berrigan, a serial recidivist, found himself behind bars for his activism. The man had chalked up a long and impressive rap sheet.

This man of the cloth, an engaged individual possessed of both a rebellious spirit and radical chic, was temperamentally and intellectually suited for the 1960s. Though he was over-educated — he has written more than 40 books, including numerous volumes of poetry — he wore his learning lightly, but wielded it earnestly. He railed against the sin of America’s imperial hubris — given the havoc that America’s B52s at the time were wreaking on the “peasants in black pajamas” in Vietnam — by arguing that the US needs to be more Gandhian and less Hobbesian. (former US presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, of course, weren’t buying.)

That is not to say that Father Berrigan rejected his church, though his church distanced itself from him. On the contrary. He seemed to postulate, in his speeches as in his books, that if there are pillars that hold up American culture, it is in the third leg of the tripod where we find the force that permeates, organises and defines our sense of ownhood as engaged individuals.

On the day he died — April 30, at the age of 94 — it was revealed that he owned nothing by way of property or earthly goods. The day after his death, the New York Times quoted his niece saying this: “Dan owned nothing. He carried nothing. Whenever I travelled with him, to conferences, speaking engagements, retreats, family occasions, he would bring that little back-pack of nothing. I’d pick him up and ask, ‘Is that all you have?’ and he would say, ‘Yes, that’s it, let’s go’.”

Yet, hyperbole aside, he changed America — not, say, as individual Americans like Cornelius Vanderbilt, John Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan and Henry Ford had done, but in his seemingly effortless style of confrontation with the monstrous evil that America at the time had loosened on itself and the rest of the world — peaceful resistance. Gandhian indeed.

I first met Father Berrigan in 1972, sitting with him under a tree on a grassy knoll at the Fordhan University campus in Brooklyn. I was then a young and starry-eyed, not to mention a starving writer living in a cold-water flat in Paris, visiting the US to promote the publication of my first book. I have to confess, shamefacedly, that I was more mesmerised by sitting next to a legend than I was by what ideas the legend shared with me about the Palestinian national struggle.

I found out about that in late October the following year when I was invited to be on a panel discussion with him at the Association of Arab American University Graduates’ annual conference in Washington, where the Jesuit priest castigated Israel for its excesses, accusing it of “seeking biblical justification for crimes against humanity”.

“It was a tragedy”, he said in his presentation, “that in place of Jewish prophetic vision, Israel should launch an Orwellian nightmare of double-talk, racism and fifth-rate sociological jargon aimed at proving its racial superiority to the people it has crushed.” He added that were he a Jew in Israel, he would be living as he himself did in the US — in resistance to the state, hunted by the authorities or in prison.

Father Berrigan, a man noted for letting the chips fall where they may and for telling it like it is, also upbraided Israel for its “repression, deception, cruelty and militarism”, and for having turned “the settler [colonist] ethos into an imperial adventure”. Whoa! And that was back in 1973, when no one dared level even the mildest form of criticism against Israel, let alone the toughest form of lambaste.

Predictably, the Jewish establishment press went down on Father Berrigan like a tonne of bricks, calling him — you guessed it — an anti-Semite. Arthur Hertzberg, the then president of the American Jewish Congress, wrote dismissively: “Let’s call this by its rightful name — old-fashioned theological anti-Semitism”.

In a eulogy, Joseph M. McShane, president of Fordham University, where Father Berrigan had once lectured, said: “Daniel Berrigan was a giant among us. Whatever one makes of his methods, his life-long pursuit of peace and justice was both heart-felt and critically important. He belongs not just to the Jesuits, but to a significant period in American history. His activism came from a poet’s heart and indeed he was always a highly accomplished poet”.

I feel president McShane couldn’t have said any better. In our part of the world, where it is a given that a “poet is to be exulted above all other mortals”, we see this as the ultimate praise.

And to befuddled millennials who’ve never heard of Father Berrigan, I say this: Enjoy your bland decade.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.