The only surprising aspect of the Russian intervention in the Syrian war was that it came as a surprise to many observers. Looking at historical precedents, and apart from a long-standing strategic alliance, Moscow had always scrambled to prevent a collapse of the ruling government in Damascus. As a matter of fact, the first Soviet veto at the United Nations Security Council in 1946 was against the extension of the French mandate in Syria.

The trend has hardly varied during the current Syrian war. Russia vetoed four UN Security Council resolutions that would have opened the door to a Libya-styled military intervention in Syria.

In 2013, when the United States came as close as ever to carrying out strikes against Damascus, Moscow scrambled to resolve the impasse diplomatically.

US President Barack Obama and Putin agreed to peacefully dismantle Syria’s chemical stockpile, but not before Russia moved its fleets to the Eastern Mediterranean. The Russians continued to play an active diplomatic role in shaping a political solution, either through the Geneva meetings, or by gathering elements of the opposition in Moscow for rounds of dialogue with the Syrian government.

Alas, military considerations won the upper hand. With an alliance of Islamist and US-backed rebels taking over the province of Idleb, Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) moving rapidly from the east after taking Palmyra, and rebel fragments on the outskirts of Damascus shelling the city on a daily basis, all meant that diplomacy alone would not suffice to defend Russia’s allies.

On September 30, 2015, Russian fighter jets began striking targets across the Syrian battlefield from their newly constructed base in the costal city of Lattakia.

Foundations for a bigger role

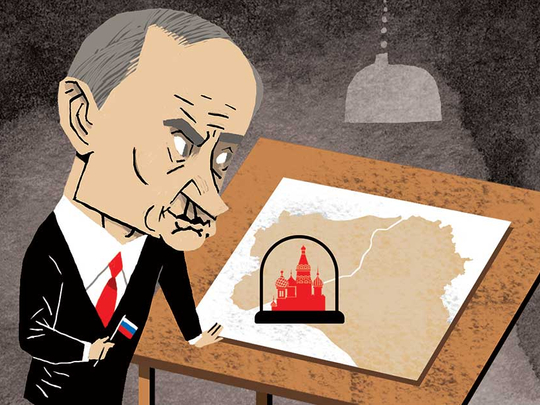

Much ink has since been spilt on analysing the motives of the Russian intervention, and on evaluating its outcomes. Apart from politicised and sentimental approaches, a careful evaluation of the Russian intervention in Syria shows that not only has Putin achieved his main objective of securing the Syrian government, he has also furthered Russia’s geopolitical fortunes and set the foundations for an even bigger future Russian role in the Middle East that will definitely extend beyond the borders of Syria.

In the first six months of its intervention, Russia was able to halt the opposition advance and secure much of the Damascus-Aleppo axis, including the vital coastal region, while boxing most armed opposition groups in the province of Idleb. Russia was able to assert itself as the dominant political broker in Syria and as a vital (and only) partner for the US, if the latter actually intended to solve the crisis in Syria through peaceful means.

This is a far cry from the tense standoff between the two powers in Europe, especially in Ukraine. Syria brought the US secretary of state and Russia’s foreign minister together for numerous meetings, and forced Obama to forego the attempt at isolating Putin following the annexation of Crimea. Furthermore, the Americans no longer demand, or are able to enforce, regime change in Damascus. There are no signs that any other player could at the moment, or in the near future, replace Russia in its political role in Syria or broker any political solution without Moscow’s active involvement.

Beyond securing the Aleppo-Damascus axis, Russia now has its eyes set on eastern Syria. Following the success in Palmyra, another Syrian-Russian advance on Al Raqqah or Deir Al Zor is now possible.

Using brute force

No matter the next objective, such a deep push east will establish Russia firmly as a partner in the global war on terror. Daesh is a mortal threat to the whole world, and if the US coalition is not ready to recognise Russia as part of it, Putin will carve out a role using brute military force.

An opening to the east will give Russia a potential role in Iraq. To secure gains in Mosul and other Iraqi cities, Daesh must be deprived of its strategic depth in the deserts spanning Syria and Iraq, and Russian forces could play such a role if it gains enough footholds in the Syrian desert. The Europeans, with their cities constantly under threat from terror attacks, will have no option but to talk to Putin when it comes to the fight against Daesh, notwithstanding their disagreement over Ukraine. So would other interested parties such as China, India and the central Asian republics.

A major Russian-Syria advance in the Syrian desert will lead Jordan and Saudi Arabia, whose northern flank is a few kilometres away from Daesh desert outposts, to consider cooperating with Russia despite political disagreements over Syria.

The intervention in Syria allowed Putin to establish himself as an indispensable partner to many regional powers, in many instances outflanking the US and benefiting from its disagreements with regional allies. Now that his troops, and his reputation, are mired in the Syrian battlefield, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan moved from clashing to reconciling with Putin. Tensions between Turkey and the US following the coup attempt, and Turkish paranoia from surging Kurdish power, give Putin an explicit political leverage over Erdogan, which he will use to further Russia’s aims in Syria and beyond. On the other hand, the Kurds are dismayed with American support for Turkey and the demands for their withdrawal from the city of Manbij. Putin will readily exploit such contradictions to draw the Kurds closer to Russia, giving him further military and political options in Syria. Baghdad, Beirut, Cairo, and Amman, not to mention the Gulf States, are also interested in what the Russians have to say, now that they have secured a pre-eminent military position in the region.

Russia’s novel position in the Middle East, entrenched as it is, will not remain unchallenged. We are already witnessing the collapse of the Russian-American dialogue on Syria and with it the prospects of cooperation against terror groups and a near political solution. The next US president could seek an assertive policy vis-a-vis the Russians, in Syria and elsewhere, which will further complicate the situation.

International and regional players could still pour arms into the hands of opposition factions to disrupt the situation along the Damascus-Aleppo axis. Not to mention Russia’s current economic problems resulting from western sanctions and the drop in the price of oil.

These challenges, however, are not enough to force Putin to retreat from the region or give up the role he had carved out in the past year, and Russia will, for the foreseeable future, remain an irreplaceable partner in the issues of war and peace in the Middle East.

Fadi Esber is a research associate at the Damascus History Foundation, an online project aimed at collecting and protecting the endangered archives of the Syrian capital.