The utterly unexpected announcement that John Boehner will step down as Speaker of the United States House Representatives and resign from the Congress this month ought to give anyone who cares about the idea of American leadership some pause.

In the short term, Boehner’s decision makes it less likely that the US will suffer yet another crippling government shutdown this week (because Boehner, freed from having to think about his caucus, can now cut a deal that relies heavily on Democrats).

Over the longer term, however, the manner of Boehner’s departure and the reasons generally assumed to be behind it are the latest evidence that something in the American system of government may be fundamentally broken and that, if so, no one in Washington really knows how to fix it.

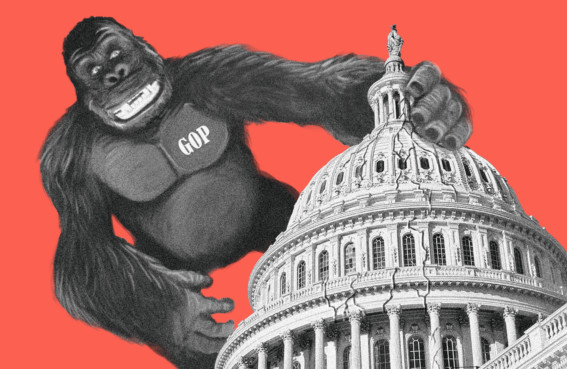

We do not know — and probably will not know for quite some time, if ever — what really went on behind the scenes over the last few weeks and what Boehner was truly thinking. The conventional wisdom, however, is that he was essentially hounded into early retirement by the farthest right-wing members of his own caucus. The GOP has a majority there but, as Charlie Dent, a Republican congressman from Pennsylvania, told the New York Times, “there are anywhere from two to four dozen members who don’t have an affirmative sense of governance ... They just can’t get to ‘yes’, and so they undermine the ability of the speaker to lead [and] they undermine the entire Republican conference and also help to weaken the institution of Congress itself”.

Politics has always been about a certain amount of posturing, about taking some positions because they resonate with one’s base, however impractical they may be. But historically, this has gone hand in hand with an understanding that being a part of government involves certain responsibilities — that even if one’s main priority is rolling back the size of government, there are certain things that simply need to get done: Debts to be paid, roads to be built and maintained, the country’s credit rating to be preserved.

The three or four dozen Republicans to whom Dent referred simply do not believe that, and unlike previous generations of politicians elected as angry outsiders have refused to adapt to the ways of Washington now that they are there.

There are many reasons why Washington has come to this. The machinery of America’s political parties has been breaking down for 50 years. The tendency of Republican elites going all the way back to Ronald Reagan to win elections by promising change to social conservatives (the sort of voters who care far more about stopping abortions than they do about cutting corporate taxes) then failing to deliver it once in office was always going to come back to haunt the party.

It became a crisis when Republicans who won office by promising to dismantle Barack Obama’s presidency discovered they could not really do that — and blamed leaders like Boehner for appreciating reality rather than themselves for promising the impossible.

And the sorry fact is that nearly everyone agrees it is about to get worse. Having driven the speaker from office it is hard to see the House’s right-wingers accepting a more moderate figure in his place. That, in turn, means that political bitterness and the sense that government itself is dysfunctional is likely to increase.

Can America really be run this way? In the short term the answer is ‘yes’ — Obama and George W. Bush before him have dealt with a bitterly partisan and often-deadlocked Congress by frequently ignoring it.

This summer’s loud posturing over the Iran nuclear deal is a perfect illustration of the point: There was never any question of submitting it to the Senate as a formal treaty. Instead, the Obama administration devised an ‘approval’ plan that was always nearly certain to result in victory and seemed mainly designed to give congressmen and senators an opportunity to vent harmlessly.

That is a poor substitute for real debate. It may lead to short-term victories, but does a lot of long-term damage as it inexorably becomes the norm for handling complicated policy issues. In a Washington where everything has become partisan nothing really gets a ‘fair hearing’ — battle lines are often drawn before there is anything formal for either side to debate.

The outsider congressmen and the outsider presidential candidates promising to change everything and end dysfunction ignore the fact that Obama won the White House nearly seven years ago by making exactly the same promise.

Both parties say they want America to “lead” on the global stage, but when Congress forces the administration to move ahead without it, America’s authority is diminished.

This isn’t a call for politics to ‘stop at the water’s edge’ (a dictum that was always honoured more in theory than in practice). It is a reminder that strong, genuine debate strengthens a president’s hand in foreign affairs — any president, Democrat or Republican — and strengthens the institution even when it loses. Too many people in today’s Washington don’t appear to understand that.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.